Father Peter McVerry has been working with homeless people for over forty years. When he started there were about a thousand homeless in Ireland. Now, there are officially about eight thousand, with many others unofficially so. Last week, Daniele Idini caught up with the legendary social justice campaigner.

Daniele Idini (DI): You have seen different types of crises related to housing in Ireland, but what are the constants?

Fr McVerry (McV): What has been constant over the forty years is the attitude of decision makers to those who are homeless. When I started, the big issue was fourteen and fifteen year old kids living on the streets. When I opened my first hostel for those kids, the attitude was that these kids who kept running away from home were bad kids, and the solution was to call the police, pick them up and bring them back home again. The idea that there was huge abuse and violence and neglect hadn’t registered yet. So, the attitude was that we shouldn’t be reaching out and helping these kids. They’re just bad kids. Then the problem shifted to young adults with drug problems and again – the same attitude. Well, these are people that started using drugs. It was their fault. So, we shouldn’t really have too much sympathy for them. Then the issue became homeless families, and again, there’s a stigma attached to being homeless, and that stigma is accepted by some decision makers. What has been constant is this negative stigma that is attached to homeless people, and affects some decision makers’ thinking.

DI: Where do you think this stigma comes from?

McV: It permeates the whole of society. The only homeless people who are visible are the ones who are sleeping on the street and begging, and who generally do have a drug problem. This leads to a perception among the public that homeless people must have a problem, and that’s why they’re homeless. But the vast majority of homeless people don’t have a drink or a drug problem. The vast majority becoming homeless today are being evicted from the private rented sector, either because they can’t pay the rents, or because the landlord says they’re selling the flat.

The land question has haunted Irish politics since time immemorial. Frank Armstrong attributes the current acute housing crisis to the colonial settlement.https://t.co/7Qp4K5wQrr@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @vincentbrowne @connolly16frank @caulmick @RoryHearne @fallon_donal

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) August 17, 2021

DI: Can we draw a connection between this and the economic policies that have been implemented in the last few decades?

McV: Well, at an immediate level, when families become homeless, having been evicted from the private rented sector, there is no social housing to move into. In 1975, this country built 8,500 council houses. In 1985, and we were in a recession in the 80s, we still built 6,900 council houses. By contrast, in 2015 this country built seventy-five council houses. So the immediate effect is that there is no housing for those families to move into. They have only got one problem and it’s not drugs and it’s not drink. They don’t have enough money to be able to go out and afford alternative accommodation.

Now, why did that happen? It happened because of an ideology. The ideology that the private sector is supposed to solve all our problems. And so, low income families were pushed into the private rented sector, which no longer can cope. But it was that ideology. We’ve privatized everything. We’ve privatized childcare, and that’s in a bit of a mess at the moment. We’ve privatized care for the elderly. Most private nursing homes are privately run. We have privatized much of the health system and now we have privatized the housing system and it simply doesn’t work.

The private market might build lots and lots and lots of houses, but only for people who can afford them. They’re in the business of making a profit. They’re not going to build housing for low income families. And so it’s the State that has to do that. The State has been very reluctant, over the last twenty years or so, to invest in social housing, and therefore they’re pushed people into the private rented sector. That wouldn’t be too bad, if we didn’t have a crisis in the private market where there aren’t even enough houses for people who can afford to buy them. It is estimated that we need between thirty-five and fifty thousand new houses every year just to keep up with the increase in population. Yet we’re only building in the region of twenty to twenty-five thousand. So there are lots of people who could buy a house, but can’t find a house to buy, and they’re being pushed into the private rented sector. So, everybody is being pushed into the private rented sector, and it can’t cope. Rents are going through the roof.

DI: In Ireland, we still have relatively high home-ownership, but, especially after the crisis, there’s a rush into the new model of renting for life. This is a bit of a paradox, however, in terms of a neoliberal ideology which aims at protecting the right to private property; yet, in Ireland, owning private property has become out of reach for a significant percentage of the population.

McV: Absolutely, yes. So over the last twenty years, the State has failed in its responsibility to build social housing, pushing people into the private rented sector. They had to create a culture for that to happen. The State did two things. First of all, it looked at the continent. It looked at the rest of Europe and said: Well, most people rent. So, any progressive democracy and an economy which is growing must have a lot more people renting. The mistake there is that the rental market in the rest of Europe is totally different from the rental market in Ireland. Most rental markets in Europe are highly regulated: prices and rents are controlled, and you can become a lifelong tenant. Here, you can’t. You get a tenancy for maybe twelve months, or at most four or five years. You’re living with high insecurity, and the rents are increasingly way beyond your means. It’s a totally different rental market to the rest of Europe. But if you read the last government’s housing strategy, there is so much ideology in it trying to persuade us that the rental market is the way we have to go. The rental market has all of these advantages, and it is the only way for a progressive economy to go.

Frank Armstrong explores the historical origins of capitalism, as the steady financialisation of property threatens the good life we have a right to expect.https://t.co/Lq7z4PeWCP@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @liamherrick @williamhboney1 @KevinHIpoet1967 @VillageMagIRE @RoryHearne

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) September 15, 2021

DI: According to a recent Irish time article Ireland has the 10th highest rate of vacant homes in the world, with 183,312 homes classified as vacant. We have a society that does not regard it’s housing stock as a basic national infrastructure like ports, rail network, airports or the electricity grid.

How might the public become more aware of the benefits of a more distributed housing stock?

McV: Well, I think the public are well aware of the empty homes that exist in every town and village. Ireland is blighted by empty properties lying derelict, often being used for antisocial or drug using young people. But there is very little political will to go after those properties. There is a lot of work involved in trying to identify the owners of some of those properties and trying to sort out any legal problems that may exist with relation to that. But we ought to be promoting compulsory purchase orders on properties that are left idle for longer than one or two years. It is a scandal. 1830,000, you mentioned. One of the issues was the Fair Deal Scheme, where if you go into a nursing home, the value of your home will be taken by the State when you die. Eighty percent of the value of your home will be taken by the State when you die to pay for your care in the nursing home. That meant that people in nursing homes couldn’t rent out the empty house they had been living in, even though they’re never going to go back to it.

They can’t rent it out because most of the rent would be simply taken up by the nursing home to pay for their care. So, you had empty houses there that couldn’t be used. You had empty houses where we couldn’t find out who the owner was.

The government did make a couple of schemes such as a Repair and Leasing Scheme where the owner can benefit from a grant of, I think it’s now €60,000 to bring the empty building back into use and then lease it to the State for a period of up to twenty years. And there was a Buy and Renew Scheme where the State could buy the property and then repair it. But there was very little uptake of those two schemes. So yeah the amount of empty properties is a scandal.

DI: What other measures would you suggest should be put in place to deal with the situation?

McV: There are two problems at the moment. One is housing those people who are waiting for social housing. There’s an even more urgent problem, and that is preventing more and more people from coming into homelessness and needing housing. That’s the more urgent problem, and that can be solved overnight.

During the pandemic, there was a ban on evictions and there was a ban on a rent increase and the number of homeless people and families dropped by almost two thousand. We should extend that to a ban on rent increases and a ban on evictions for at least three years in order to try and get a grip on the problem. The counterargument will be that it’s against the right to private property. But I don’t buy that argument. I don’t think the Supreme Court would uphold that argument.

So the solution involves passing a law banning evictions and rent increases and sending it to the President to sign. The President can send it to the Supreme Court and fast track a decision. Let’s do that. Let’s find out if it’s against the Constitution. If it is, you bring in a constitutional referendum on the right to housing and make that right at least place level with the right to private property, because every argument we present to try and address the housing-homeless crisis comes up against the argument that it is against the right to private property in the Constitution. Now, that right to private property was established in the 1930s at a time when Communism was expanding around the globe. And one of the tenets of communism was that you could not own private property. So, the idea behind it was to prevent Ireland ever having a Communist government. But now it’s being used to prevent Irish people getting their own home, which is absolutely absurd.

A fascinating insight into the mechanics of dysfunction in housing. Great work by

Daniele and Liam. https://t.co/dI7pQ4CXu2— Chay Bowes 🏴☠️ (@BowesChay) September 18, 2021

DI: Isn’t it a paradox that a good percentage of the population does not have access to private property because we have to defend the right to private property?

McV: Yeah, it is a total paradox. The Catholic Church, for example, supports the right to private property, but what is meant by that is that everybody should have access to private property because that’s our little security. That’s their little fallback if things go wrong. But the right to private property has been hijacked by the wealthy to hold on to what they have already acquired. And that was never, never the intention, certainly of the Catholic Church in supporting private property.

DI: Is there space here for a discussion of morality? Is it morally right to continue pursuing economic policies which, as experience is showing, are causing unnecessary pain and suffering to a growing percentage of the population? How do indicators such as GDP relate to the percentage of homelessness?

McV: Firstly, GDP is a very ineffective criterion for the wealth of a country. Every time there’s a car accident, the GDP goes up because the cost of repairing the car and the cost of treating the victims all adds to GDP. And the more serious the car accident, the further GDP goes up. So, GDP is not a reflection of the wellbeing of a society. We can never agree on what is moral. If you own a big house in a nice area with a nice car what is moral is your right to protect those assets. But if you’re homeless on the street, your concept of morality is going to be very, very different. So, I don’t think we’ll ever agree on what is moral. This is a political question. This only way it is going to be solved is politically. We have to ask the question: who benefits from rising rents and rising house prices? The answer is three groups.

One, the banks. The banks benefit because as house prices go up, they can lend more and more money out as mortgages and make more profit. And if they repossess a house, they will get more money for that house. They have an interest in a house and rent goes up.

Second, the big international investment funds. They also have an interest in rents going up. And indeed, many of them are leaving some of their properties empty rather than reducing the rents to what people can afford.

Third, the Landlords.

But who doesn’t benefit? Almost all Irish people don’t benefit from rising house prices and rising rents. For most people it is a huge disadvantage.

The second question we have to ask is which side is the government on? The government is on the side of the banks, the big international investment funds, which they attracted in with extraordinary tax concessions, and it’s on the side of landlords.

In one episode Simon Coveney brought in a rent cap of four percent. Where did that four percent come from? Simon Coveney wanted to bring in a rent cap in line with inflation, which was hovering around zero at that time. The big international investment funds held a number of meetings with the Minister for Finance and told him that four percent was the minimum they would accept if he wanted them to continue being involved in this country.

So four percent it was, and since then the rents have gone up far more than that. In those five years, the rents have potentially gone up by twenty percent. At the same time the HAP payment which you received from the government if you’re on a low income hasn’t gone up in those five years. So now the rents are on average twenty percent higher than they were when the payment was introduced, and lots of people are having to pay top ups to the landlords. Anything between €125 and €200 is what I’m coming across. And you have a single person on social welfare who’s getting €204 or €205 a week, and they have one week in a month where they have to pay €200 to a landlord as a top up because the HAP payment hasn’t increased sufficiently.

People on low incomes are just being screwed, screwed by landlords, screwed by investment funds, screwed by banks, and the government is on their side, not on the side of renters or people paying a mortgage who are struggling to try and keep their heads above the water.

As livelihoods decline in the wake of the pandemic, David Langwallner argues that courts must now vindicate a right to housing and other basic requirements.https://t.co/D0m1oIRoqG@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @KevinHIpoet1967 @RoryHearne @caulmick @williamhboney1 #HousingCrisis

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) September 21, 2021

DI: The inability of successive governments in dealing with this issue is more and more being perceived by the public as the result of either State corruption or pure negligence.

McV: I wouldn’t call it either of those. We have had conservative governments. Conservative governments are on the side of those who own capital because it’s the capital that develops the economy. So they’re on the side of capital, of the capital owners, which are the banks, and the large investment funds. And they don’t want to do anything which would frighten any of those away, anything which would make Ireland a less attractive place for them to operate. So I think there’s a conservative mindset which I totally disagree with. It’s not a mindset I would put down to malice or corruption or anything like that. I would put it down to what I would consider a very, very mistaken perspective on what’s happening in the country.

For example, in Germany they have passed a rent freeze for the next five years on rental properties, and in Berlin, they introduced a referendum to take back from the big international investment funds all the apartments and buildings that they had built. Now, it probably won’t pass, but that’s the sort of thinking we need to do. That sort of thinking is totally absent in Ireland.

The people who make the decisions here are doing very well. They’re on good salaries. They live in nice houses and nice parts of the town. Their children are going to third level education and in a few years time they’ll live in a nice house in a nice part of town. So they have a different perspective from somebody who’s struggling to pay the rent. They don’t understand somebody who is struggling to pay the rent. They say they do, but they don’t. For them the housing problem the problem of people on low incomes struggling to pay rents and mortgages. That’s a problem in a file on their desk. It’s not a personal problem for them, and it’s not a problem anybody they know is facing.

So for them it’s more theoretical. For me it’s real. It’s real because I’m meeting them every day and I’m frustrated and I’m angry. I want to see somebody with a passion for dealing with this. I want to see a decision maker who has a passion for dealing with this, who’s angry about what’s happening and who’s prepared to put their neck on the line. That’s what I want to see. I don’t see it at the moment.

DI: And as we are coming slowly out of a pandemic, what lessons can be drawn in regard to emergency accommodation and homelessness?

McV: The pandemic actually had one positive feature for homeless people. They were able to get accommodation because a lot of Airbnbs came back into use as private residential accommodation. And because there was a pandemic, you didn’t have queues of people outside wanting to view them. So landlords were ringing us and saying, You have anybody that needs a place? And they knew we wouldn’t put in somebody who was going to wreck the place. They knew we would support that person. And if difficulties arose, we’d have to step in. So it was a Win-Win for everybody.

Now is the time to regulate and demand that Airbnb’s get planning permission and to regulate, inspect and ensure that those planning permission and regulations are enforced. That would bring a lot of Airbnb’s back into private residential properties and would be a big addition in helping the housing crisis. It could be a condition that anybody who wants to advertise their property on one of the sites, like Airbnb, must produce evidence of planning permission. That would get rid of a lot of Airbnbs and bring them back into residential use.

Banker Ben Hoey identifies a solution to the #housing crisis to level the playing field between institutions and individuals paying over the odds on mortgages.https://t.co/rsw0UPoWCe@broadsheet_ie @beny987 @BowesChay @paddycosgrave @RoryHearne @VillageMagIRE #generationrent

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) October 6, 2021

DI: With tourism opening up again have you noticed any effects on homeless people, who were housed in hotels and hostels during the pandemic, and are now, again having to rely on shelters?

McV: That’s already happening. The lease is now up on a number of hotels that were taken over as accommodation for homeless people, and they have been returned to the owners to be used as hotels. And it’s a real pity because homeless people love the hotels. You have your own en suite room. And now some of them are getting thrown back into hostile situations, and it’s very depressing for them. So yes, that was a feature of the pandemic that’s now disappearing. And it won’t come back.

One option is to buy those hotels, buy them back, buy them from the owners and use them as accommodation for families and that, but that’s very expensive. They’re not going to do that.

One of my ideas for homeless hostels is that everybody should have their own room. Homeless hostels are often unsafe. Many people get assaulted. People’s belongings get robbed. I’m arguing that every homeless person should have their own room all the time that provides security and safety for their belongings.

That’s expensive, and they’re not going to do it. It’s much cheaper to get a house and put four people into a room with bunk beds than to provide four separate spaces for homeless people. So, they’re not going to invest the money in that. But to my mind, what we offer to homeless people sends a message to them, and the message is, this is how society values you. This is what society thinks you’re worth. So when you cram them into rooms and bunk beds, some rooms without even a window in it, they’re getting the message. And that message is very negative. But that is the message that many of our decision makers don’t mind giving to homeless people because that’s the attitude that they’re coming from. This is good enough for them. I heard one person ringing up the free phone number to try and get a bed for the night, and he was offered a bed in a hostel. And he said, I can’t go to that hostel. It’s full of drugs. I don’t use drugs. And the answer I overheard was “beggars can’t be choosers.” And that’s the attitude I think that many people have towards homeless people.

It is an attitude that has political ramifications. Why else would we have reduced our building of social housing? Whenever the state tries to build social housing, you’re going to have huge objections from all the neighbours. And the local councillors who have to approve of social housing in that area are looking to the next election. And if they are alienating the people in the area where the social housing is going to be built, they are not going to approve that social housing for fear that they will lose out in the next election. So, we have this attitude that anybody in social housing is undesirable. Anybody in social housing is a problem, has a problem and therefore we don’t want to be anywhere near them. And the political system has to go along with that because of our democracy.

With editorial from Ben Pantrey.

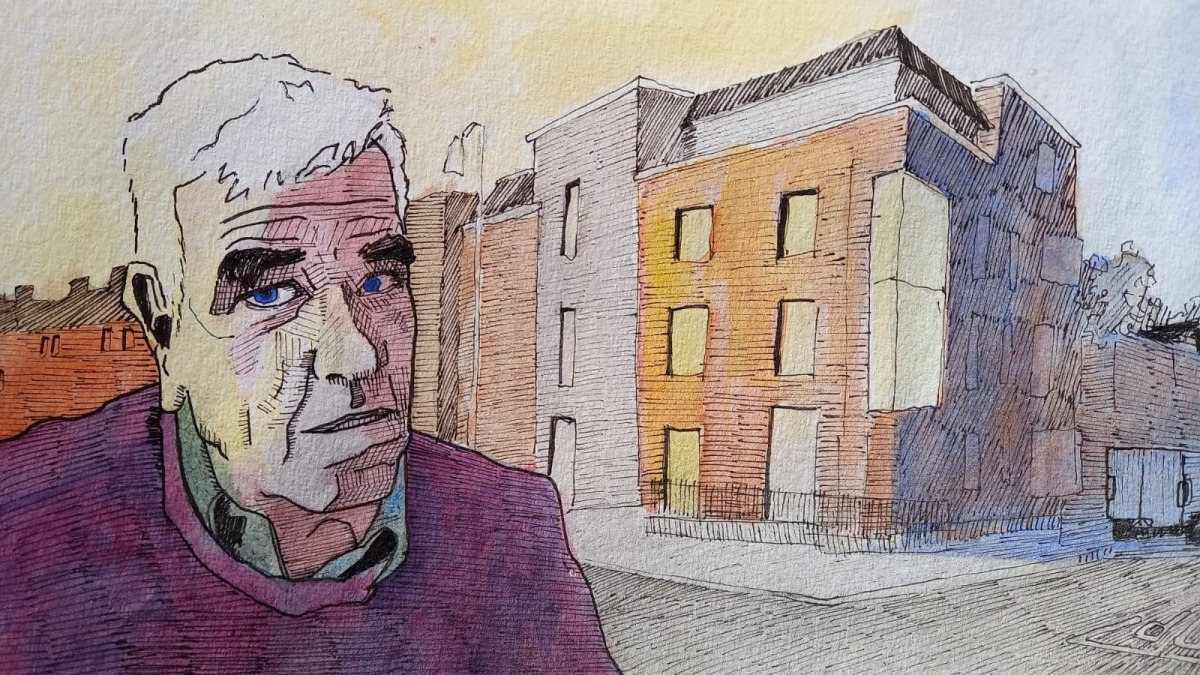

Featured Image by Gareth Curtis