In this second article Lorcan Mac Mathuna discusses his An Bhuatais & The Meaning of Life a book and CD collection of contemplative songs and essays.

Lorcan Mac Mathuna's An Bhuatais & The Meaning of Life draws on the exquisite portrayal of drama and character archetype in ancient Irish mythology.https://t.co/T1Uzo3FZJH@broadsheet_ie @IlsaCarter1 @wadeinthewate11 @Andrea_Rey48 @diarmuidlyng

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) February 25, 2021

The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.

L.P. Hartley

The earliest written accounts of war portray a merciless and vicarious world where the deeds of men are steered by the caprice of malicious gods, and the deeds of warriors are frequently elevated to the plane of the gods. Indeed one of the first historical accounts of war, the battle of Megiddo 1479 BC, portrays the Pharaoh, Thutmose III, as a sort of indestructible God figure.

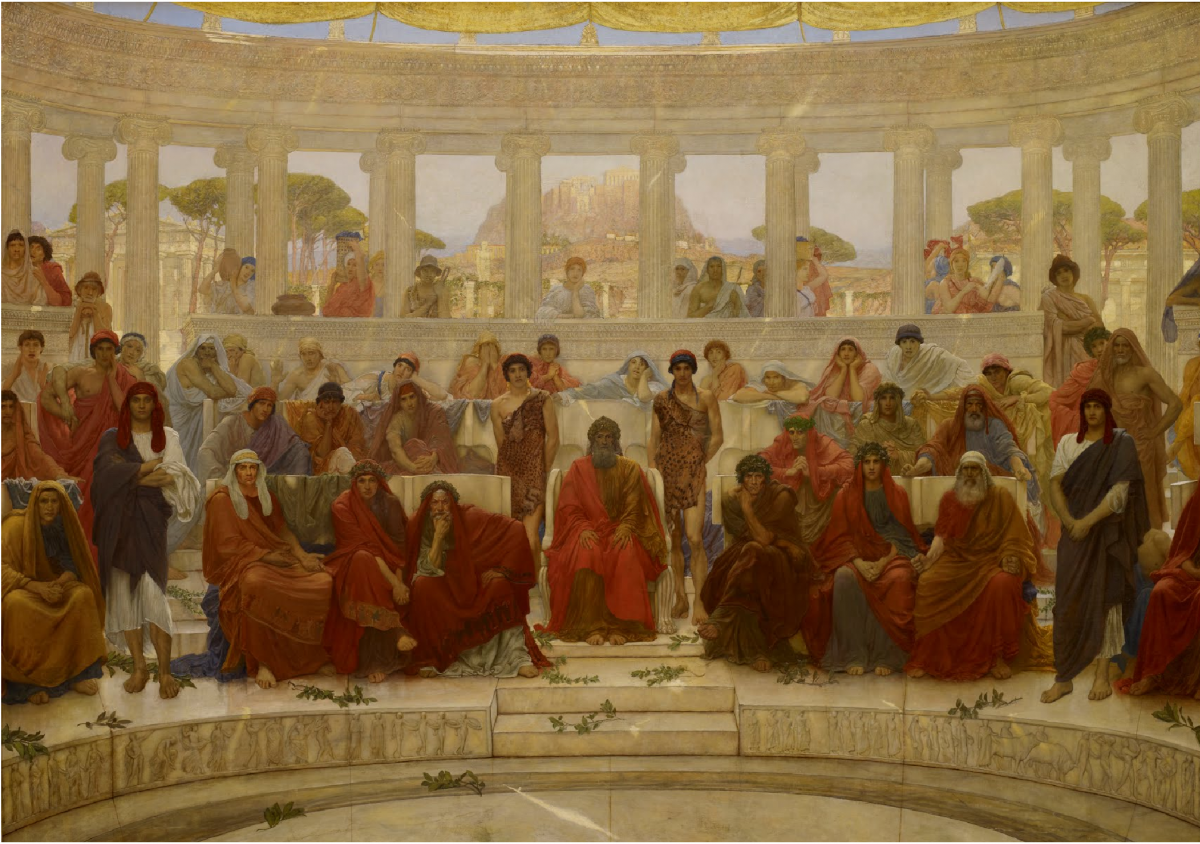

The deific depiction of the ‘hero’ is similarly featured in the mythological portrayals of conflict in the Celtic epic of The Táin and the Trojan epics of the Greeks. The extraordinary feats of CúChullain and Achilles raise the archetype of war to the plane of the supernatural.

The Greeks, under the bloodthirsty warlord, Agamemnon, despoil the plains of Troy and relish the viscera of indiscriminate slaughter. All the while the gods entwine fate and death in a mythological fabric.

The Táin, an Irish epic set in the time of Christ, has the same archetypical representation of the supernatural personality of death and slaughter that the Trojan epic portrays, including a vain and capricious God: the Morrigan.

The 12th Century accounts of The Battle of Clontarf (track 8) again represents the battlefield encounter with mortality as a supernatural narrative containing a mythological manifestation, or personification, of Death.

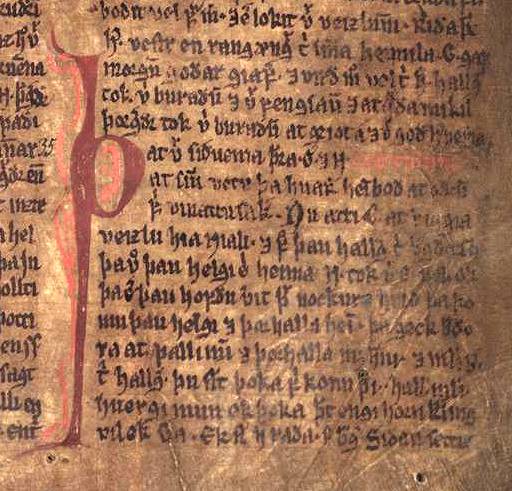

Excerpt from Njáls saga in the Möðruvallabók (AM 132 folio 13r) circa 1350

An intriguing metaphor of death is given in an Icelandic account of Clontarf, in Njáls saga. It describes a scene of Valkyries meeting in a cottage to weave the fate of the champions of the battle with a warp and weft of the entrails of the fallen. This is witnessed by a farmer named Dörruðr who describes the scene:

“Men’s heads were the weights, but men’s entrails were the warp and weft, a sword was the shuttle, and the reels were arrows.”

In the Gaelic account, ‘The Badb’ [baw -v](the Raven of Death) hovers over the battle. Into this visceral arena, demons and spectres cram, tearing at the warriors, while The Badb decides which souls to pluck from the slaughter.

This representation of a supernatural fate directed by the hands of capricious gods is the mythological embodiment of violence – what some psychologists have termed ‘the death instinct’.

It is the opposite of reason. It is an attempt to feed our imaginative understanding, and an attempt to give an essentialist grasp of the cruelty of nature. It stipulates that man and nature are entwined, and that man is therefore slave to unpredictable nature.

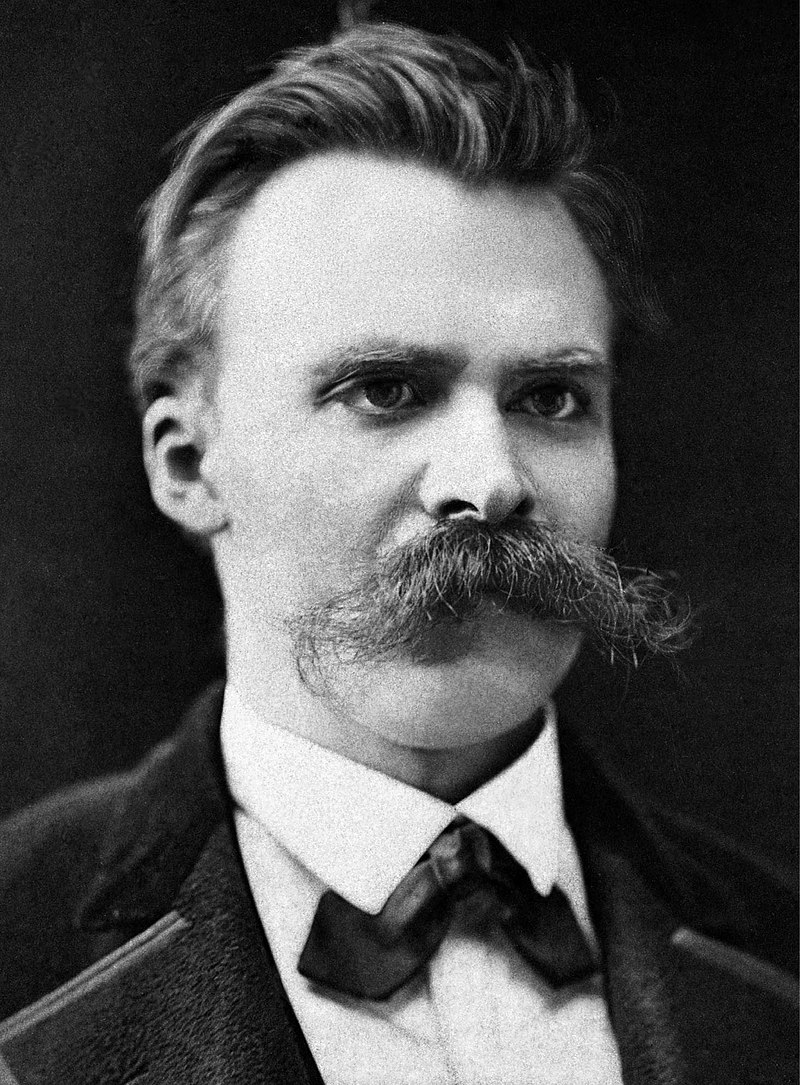

The ‘heroic’ mode of being in these epic poems has been described conversely as role fulfilment, and as an assertion of will. The latter is encapsulated by Nietzsche as an individual existence that struggles toward the ‘Overman’. Nietzsche represented this in the extraordinary scene in Thus Spoke Zarathustra where the acrobat walks between buildings on a tightrope.

Friedrich Nietzsche

In, Nietzsche, and the Myth of the Hero, Nikos Kazantzakis states:

it is the process that makes the hero – the adventurous space between his departure and his return. He stands firmly only on the towers, but what defines him as a ‘skilful’ or a ‘clumsy’ acrobat is the walk. The ‘fabulous forces’ that this Nietzschean hero must encounter are the “spirit of gravity,” the ‘nausea,’ and the figure of the ‘jester’.

The role of the jester is essential in this heroic model.’ The acrobat, by living outside of the constraints of history; by transcending through his heroic struggle in the uncertain space between the buildings, is given a greater horizon and an insight that is not open to the watchers in the square. By assuming the heroic role he ascends to the place of the ‘Overman’. The same is true of the ‘Hero’ in the epic poems of the Táin and the Trojan Epic. It is not so much that they transcend linear history, but that they transcend an archetype that is ever present in a parallel view of history. In this view, the past, the present, the future, are simultaneous.

In the ‘heroic’ society, death is a form of defeat but not necessarily so. The ceremonies of burial bridge between the role of the hero and the immortal afterlife; whilst a desecrated corpse is a supernatural death. Sophocles took this idea and created the tragedy of Antigone where King Creon punishes the dead Polyneices by prohibiting his burial. In doing so he is murdering the corpse of the hero. The consequence of this are societal-shattering, as were the new ideas of philosophy for the ancient Greeks.

In the ancient Homeric world, as in the Celtic heroic world described in The Táin, the slave is symbolically dead, because the Slave cannot take the heroic course of action (this notion was carried through to the first conceptions of democracy in ancient Athens where only citizens could take part in civic life).

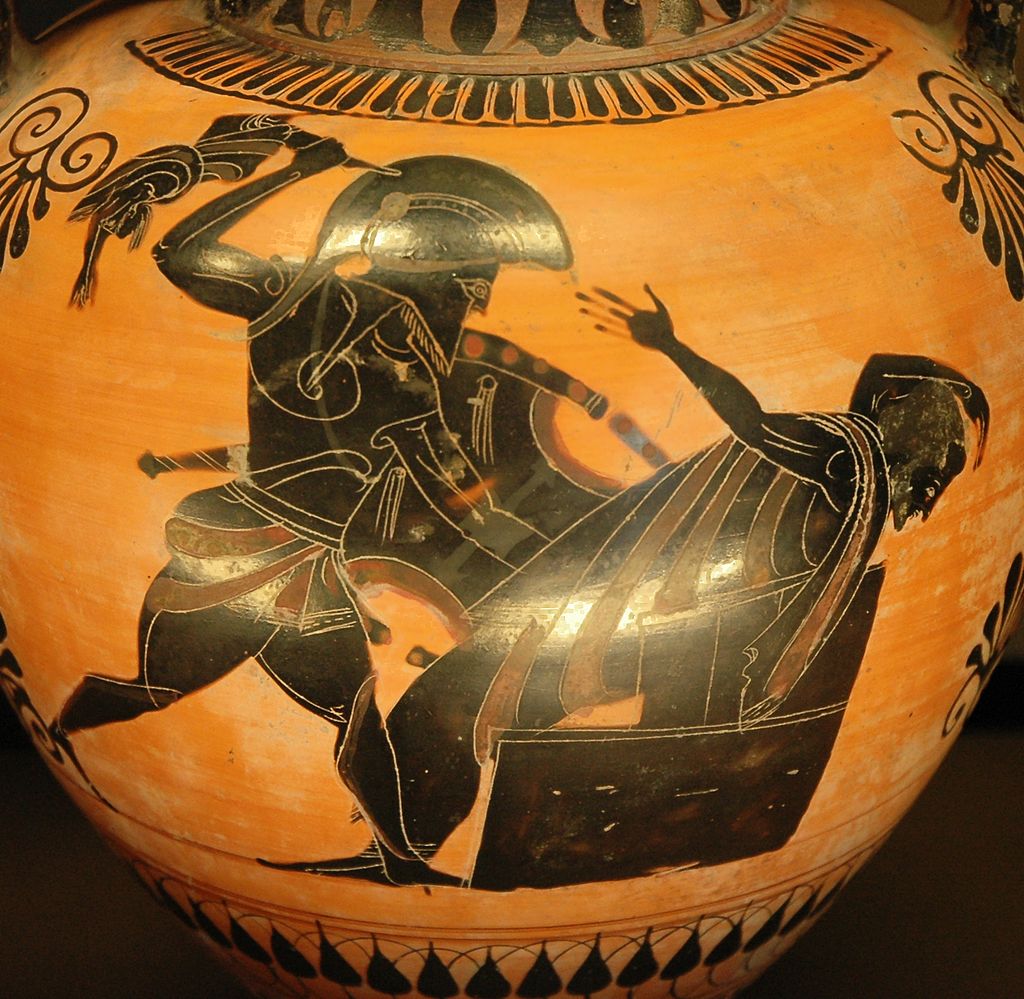

In this world-view, to supplicate oneself is death in the same sense, as it is a relinquishing of the role of the warrior. There is an intriguing paradox told in The Iliad after Achilles desecrates the corpse of Hector by dragging it behind his chariot on the plains below the city wall. Priam, the king of Troy and father to Hector, supplicates himself before Achilles so that he may tend to the corpse of Hector.

The role of Hector as a heroic character is at stake here. If he is accorded the funerary rights of the heroic, his heroism remains symbolically alive, whereas the desecration of his corpse is the death of his heroic character. We see the remnants of this psychology in honour cultures.

Priam, Hector’s aged father, gives up his own heroic life by becoming a supplicant. Priam dies, so that Hector lives.

Priam killed by Neoptolemus, detail of an Attic black-figure amphora, ca. 520–510 BC

But, if we were to look at this episode through Christian eyes we would say that Priam has gained eternal life by relinquishing his public role as king, for that of grieving parent. This is a new concept of virtue, where virtuous action is not defined by role, but is universal and objective.

In the heroic poem a virtue is a quality which enables a person to act in their well-defined social role: the warrior king, for instance. The Homeric idea of virtue can only be determined after we know the roles expected of the character. The concept of what anyone filling that role ought to do is a-priori to what is virtuous.

In Njáls saga – the Icelandic account of the Battle of Clontarf – we are given another alternative on the conception of virtue and the way to act in the world.

During the rout of the Viking host, one of their warriors, Thorstein Hallsson, stopped running and tied up his shoe-thong. An Irish warrior, Kerthjalfad, asked him why he was not running.

“Because,” said Thorstein, “I cannot reach home tonight, for my home is out in Iceland.”

This was seen as a very human assessment of the facts, and so Kerthjalfad spared his life.

It’s interesting that as the modern era of reason progressed, along with the ability to control our conditions of living, the mythologising of death and the representation and acceptance of cruelty has declined. It seems that the death instinct so often remarked upon, is not an innate part of the psychology of man. The Gods in these ‘heroic’ stories are projections of deep social adaptations of their age.

Compare this search for a mythological “will to power” with Solzhenitsyn’s search for truth and what he termed the dividing line between good and evil “that runs through every human heart”. Solzhenitsyn clarifies something revolutionary, which was earlier echoed by St. Paul in his letter to the Romans: That hell is created within the corrupted soul.

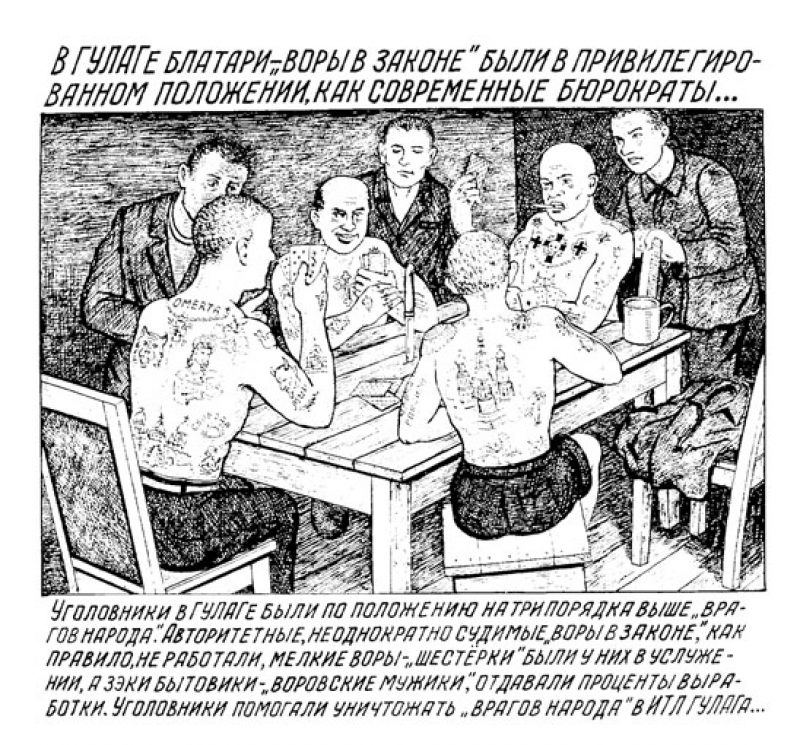

Hell is the perversion of human nature through the unfettered feeding of the darkest of human propensities. The Russian cartoonist Danzig Baldaev dealt with his immersion in hell by recording the casual sadism he witnessed daily as a gulag camp guard.

Image from Danzig Baldaev’s Drawings from the Gulag.

Danzig had to deal with two terrors: The sadism of his fellow guards, which was inflamed by a malevolent system corrupted to its very core by the philosophy of Marx. And secondly; his complicity within this network of evil.

Danzig dared not make the slightest protest against the evil in which he was immersed, because to do so would have placed him within the ranks of the victims. One way to survive was to live a demoralizing lie as Danzig did.

Danzig fought the lie by recording his images in coded hieroglyphs that only he could understand. He redid his drawings with all their horrific realism when the danger of discovery abated after the death of Stalin.

His drawings from the Gulags are testimony to observations made by both John Paul Sartre and C.S. Lewis. While Sartre said that “hell is other people”, Lewis more astutely observed that “the door of hell is locked from the inside.

What all these have discovered is that evil is separated from good by a philosophical perversion. There is nothing irrational in going from the acceptance of nihilism to becoming a guard of the gulag. It’s the fundamental values we hold that determine the morphospace of possible social relationships and systems. Solzhenitsyn went further than Danzig in his exploration of the ethics of deception. He determined that the only way to combat untruth was to live truthfully. His greatest achievement, The Gulag Archipelago, is a monumental testimony to his realisation.

The evolved ethical sense in the age of Gods and Heroes is different to that in the modern age of reason. What is adjudged ‘good’ in the heroic age – the act of slaughter in battle for instance – has no common fundamental with the modern ethic of ‘good’; where moral pre-eminence is given to an empirical view of the world. These fundamental psychosocial understandings of the correct way to behave – for which we sometimes use the intangible proxy of ‘good’ – shift with philosophical revolutions. This shifting of the perspective is a constant feature. It is hard to say that the perspective of the age is the definitive and final destination. The postmodern ontological view has shifted the view of ‘good’ away from empiricism and reason, and may yet have catastrophically regressive effects. One thing for sure is that we have not reached “the end of history.”

Band Photography | Musicians | | Holst Photography Ireland

An Bhuatais & The Meaning of Life is available through:

Website:

www.lorcanmacmathuna.com

Bandcamp:

https://lorcanmacmathuna.bandcamp.com/album/an-bhuatais-the-meaning-of-life

Spotify:

https://open.spotify.com/album/4ughUTW4jIawqVLiY8D5am?si=p6hJeIqsS0yr_3HgPBv2Kw

Feature Image: William Blake