Often dismissed as ‘worthy’, but perhaps overly wordy, products of the nineteenth century, the novels of Charles Dickens retain great wisdom argues human rights lawyer David Langwallner, who explores aspects of the author’s work to inform an understanding of contemporary challenges.

Dickens and the Law

Jaundice and Jaundice drones on. This scarecrow of a suit, has, in course of time, become so complicated that no man alive knows what it means. The parties to it understand it least; but it has been observed that no two Chancery lawyers can talk about it for five minutes, without coming to total disagreement as to all the premises.

Charles Dickens, Bleak House, (1853).

It remains the case that real compassion should animate my legal profession, not the enduring casuistry and competition that Dickens observed in his time. This is not fake compassion but such that reveals a refined understanding of the human condition. This should also feed into judgment. Above all else a judge should be compassionate, occasionally bending the rules to achieve a compassionate result in the circumstances of an individual case.

People often leave courtrooms with a burning sense of injustice, having had their lives ruined. Compassion mitigates such unpleasantness, curbing the excesses of an imperfect system. Legal advocacy should not all be about winning, although in the heat of battle it may seem so. Ultimately, it is about the service of justice, and what happens to the poor misfortunates presenting in court, who are not so very different to those of Charles Dickens’s time.

This idea was beautifully expressed by the legendary English barrister Sir Edward Marshall Hall In 1894 when he defended the Austrian-born prostitute Marie Hermann, who had been charged with the murder of a client; Marshall Hall persuaded the jury that it was a case of manslaughter. Although he made full use of his oratorical skills, the case is best remembered for an emotional plea to the jury at the end: ‘Look at her, gentlemen… God never gave her a chance – won’t you?’

Of course the law of equity permits, indeed requires, a judge to do justice or equity. This involves finding a solution suited to an individual case. Thus, injunctions are discretionary remedies. Many, though not all judges, take this responsibility seriously. He who seeks equity must do equity.

In a sense the maxims of equity are the moral bedrock of the legal system. They exist in principle but often in our Courts of Chancery alas – particularly in highly expensive banking cases – lawyers often behave like those observed by Dickens in Bleak House.

But what chance today for the little person against the deep corporate pockets? Should the poor still have to submit to the humiliation of requesting for one more spoon of gruel? Charles Dickens may yet guide us through the spectral forms of the legal past, present and yet to come.

Lawyers Abound

Illustration for “The Children’s Dickens: Stories selected from various tales” (1909) London: Henry Frowde and Hodder and Stoughton by Gilbert Scott Wright.

Lawyers appear in no less than eleven of Dickens’s fifteen novels. Some even resemble human beings, though not pleasant ones. Uriah Heap from David Copperfield (1850) is a ‘red-eyed cadaver’ whose ‘lank forefinger,’ while he reads, makes ‘clammy tracks along the page … like a snail.’

Meanwhile Mr Voles from Bleak House is ‘so eager, so bloodless and gaunt,’ that he is ‘always looking at the client, as if he were making a lingering meal of him with his eyes.’

Dickens, like Kafka, that other great writer about the law, was experienced in the trade. Aged just fifteen, he was hired as an ‘attorney’s clerk,’ serving subpoenas, registering wills, copying transcripts. He went on to became a court reporter: for three formative years commenting on the chaos of the Victorian profession. At thirty-two he filed his first suit against a pirate publisher, and would spend most of his life lobbying for copyright reform.

Dickens’s response to one copyright suit, expressed to a close friend, might serve to encapsulate his entire view on the system of justice in his time: ‘it is better to suffer a great wrong than to have recourse to the much greater wrong of the law.’

Greedy Businessmen

Bleak House best presages perhaps our day and age. Spare a thought this Christmas not for lawyers, but lay litigants dealing with receivers and bankruptcies. Are we really saying to families this year that if their homes are repossessed that they and their children will be put on the street?

Then there are the Christmas stories including the seminal A Christmas Carol (1843) with the notorious Ebenezer Scrooge, the archetypal dishonest and exploitative businessman, wholly dedicated to the pursuit of profit at the expense of others.

Scrooge is not an isolated example. Dickens’s oeuvre is populated by an array of greedy Victorian businessmen, such as the infamous Mr Gradgrind in Hard Times, among a plethora of unscrupulous lawyers who, as a profession, are on the receiving end of the full force of Dickensian odium. It is the culture of greed and human exploitation that most strokes his ire.

Famously in A Christmas Carol Scrooge Is visited by ghosts of past, present and yet to come. In an unlikely twist of fate, the miserly man of commerce recognises the perversity of his ways, especially in his treatment of Bob Crotchet and his destitute family. Scrooge repents – deus ex machina – after a ghostly visitation by his ex-partner who he drove to an early death, and also a pitiful vision of the the Cratchet family should he persist.

Scrooge and Bob Cratchet

Dickens was the great chronicler of the instabilities and social malaise of Victorian society to which our current age of increasingly unchecked capitalism may see us return to. This theme was taken up by George Orwell in ‘How the Poor Die’ (1946) and The Road to Wigan Pier (1937), and he lauded him thus in another piece:

Dickens attacked English institutions with a ferocity that has never since been approached. Yet he managed to do it without making himself hated, and, more than this, the very people he attacked have swallowed him so completely that he has become a national institution himself.

Thus Dickens spoke for the poor of Victorian England, and is the prototype of a public intellectual, having not limited his writing to fiction.

Debt Laden Age

In terms of our debt-laden age David Copperfield is also peculiarly relevant. Mr Micawber defines the difference between happiness and unhappiness after he ends up in a debtor’s prison:

My other piece of advice, Copperfield,’ said Mr. Micawber, ‘you know. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds nought and six, result misery.’

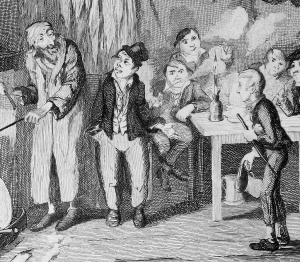

David Home illustration from Character Sketches.

The abiding message is to take care of the pennies and the pounds will look after themselves. It seems a foretaste of Thatcherism – the penny-pinching approach to government of ‘Forthright Grantham grocer’s girl’. This is the commoditization of everyday life, where one’s income is an index of one’s happiness. This idea has clearly penetrated into Mr Micawber’s consciousness, as indeed it has been largely internalized in our present age.

Invariably still, it is the little man or woman who meets trouble, with ever disproportionate inequality and wealth cartelization threatening economic and ecological meltdown.

And in Dickensian fashion, the super-rich or the banks ‘too big to fail’, the speculators and lawyers who have facilitated dodgy loan instruments work away safely in well-appointed homes at a far remove from the consequences of their actions.

Since the last recession, especially under David Cameron in the UK – but perhaps especially in Ireland after the EU/IMF bailout – austerity measures were used to balance the books and pay for costly mistakes at the behest of large corporations that then preyed on the economic debris.

Christmas Chronicler

To revert to Dickens as the supreme chronicler of Christmas. If someone has the temerity to present themselves like Oliver Twist with an empty bowl and ask for more will our modern day workhouses permit another spoon of porridge?

Or will they ask: ‘are you not happy with your existing pile of gruel – the charitable food banks that ease the conscious of the rich?’ Now with Covid-19 restrictions in full force diminishing most incomes – but especially those least well off – many now need a bit more, just to survive. This should involve chasing down the artful dodgers in the large corporation, who have picked a pocket or two avoiding paying their fair share of tax.

George Cruikshank original etching of the Artful Dodger (centre), here introducing Oliver (right) to Fagin (left).

Yet it is still open to those in authority, like Scrooge, to mend the error of their ways and reflect on how incompetence, greed and neo-liberal norms are destroying the social fabric. Indeed in some respects social distancing seems a perfect neo-liberal ploy, allowing elites to remove themselves entirely from the great unwashed, or diseased ‘other.’

Copyright

Finally, one of Dickens’s bugbears was the impact of pirate printers on his book sales, especially in the unregulated free market of America, where outright banditry took the place of copyright law. On his first visit to America Dickens incurred the wrath of the Boston press by lobbying in what was supposed to be a polite after dinner speech for international copyright regulation.

In Hartford Connecticut, in a hushed voice, he revisited the theme. In a voice likened to thunder, he claimed Walter Scott would not have died in penury if such a law had existed. This brought howls of rage from the press galleries. Dickens was, however, defended by the legendary Horace Greely of The New York Tribune with the Delphic phrase: ‘who should protest against robbery but those robbed.’

This is the situation that many in the music industry find themselves in today, as platforms such as YouTube and Spotify offer few rewards for artists, who are now no longer even able to play live gigs in our current time.

Occasionally noble sentiments in preserving intellectual property are carried too far. Thus, as Irish Senator David Norris pointed out, the James Joyce estate sued the living daylight out of anybody who had the temerity to breach copyright. This allowed his grandchild to profit from the labour of a long deceased author. Joyce passed away in 1941, but the copyright lasted another seventy years until 2011. Author’s rights should be protected but not excessively.

Dickens in New York, circa 1867–1868.

Yet to Come

At least this Christmas – which alas may be the grim version of Scrooge’s dark imagining – we might use the down time wisely and take a dusty copy of one of Dickens’s tomes from off the shelf. Readers are sure to find guidance for the times we are in. Then perhaps 2021 will be a year when we begin to mend our ways, like Scrooge himself.

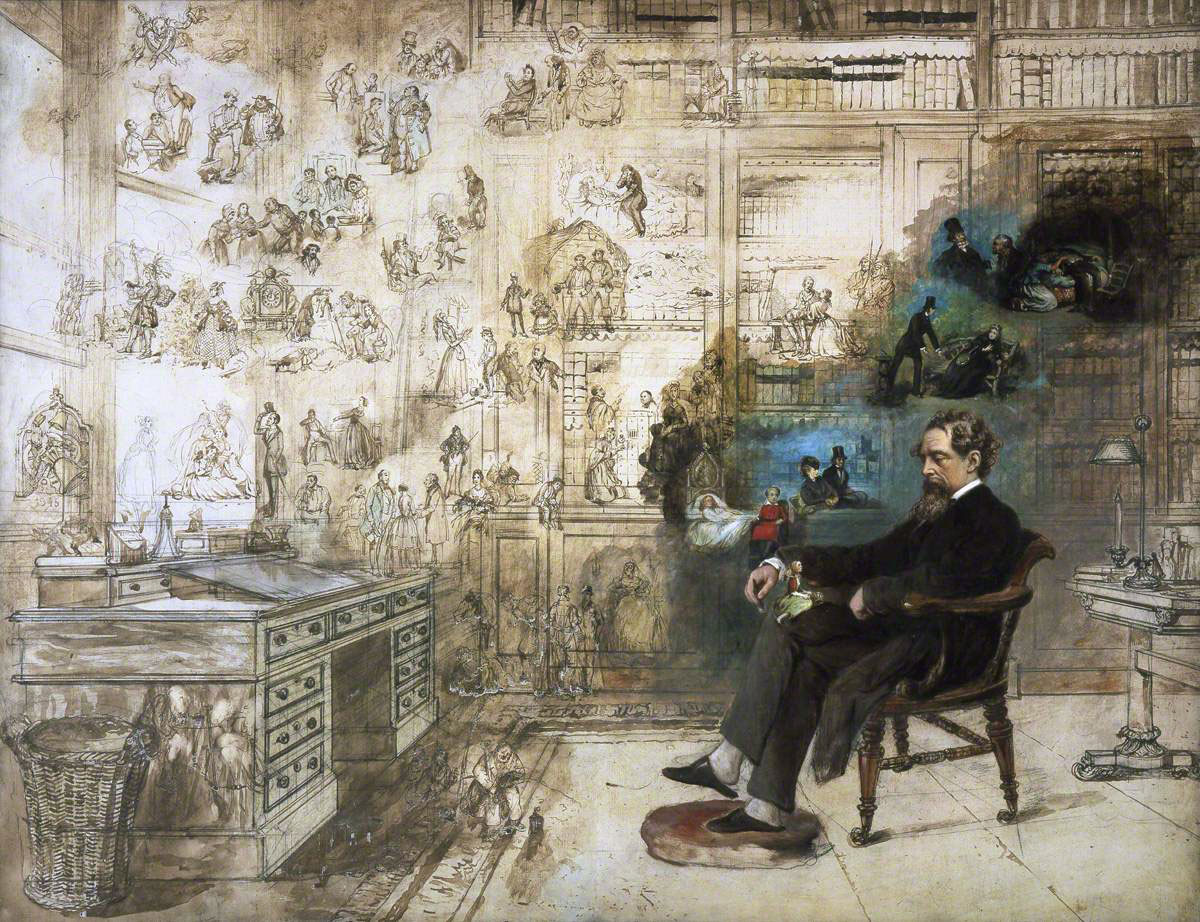

Featured Image: Dickens’s Dream by Robert William Buss