Undeniably, Ireland has produced some of the finest creative writers in the history of the English language. From the Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) through to Samuel Beckett (1906-1989), who ultimately abandoned English in favour of French, a body of work has expressed a contradictory national character.

A recurring theme in Irish writing has been what a therapist would refer to as abreaction – the expression and consequent release of a previously repressed emotion. Thus, the drama of colonisation and sectarian division enthralled a global audience, at a remove from what is often the painful direct experience of a dysfunctional state and troubled society.

On the other hand, we have seen little in the way of philosophical wisdom in Irish letters, apart from George Berkeley (1685-1753), and Edmund Burke (1729-1797) at a stretch. So Ireland must make do with imaginative writers as intellectuals: our novelists of departure, and poets of abstraction.

I had the good fortune to encounter in the flesh arguably the last in the line of towering figures, Samuel Beckett, in a café in Montparnasse, Paris in 1982.

Ireland had just won rugby’s Triple Crown in what was then called the Five Nations, before succumbing to the French team at the Parc de Princes, and Beckett was primarily inclined to banter about rugby and cricket with his countrymen. It must be stressed that he was a charmingly convivial person, and while austere, decidedly good company; even when pressed to do so he sedulously avoided discussion of his own work, preferring to muse on the artistic contributions of others.

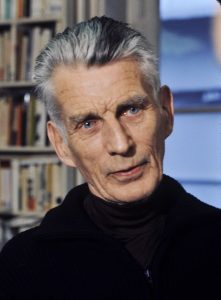

That slightly detached dignity, captured in John Minehan’s award-winning photograph was exactly as I found him. A kind and decent man, who concealed a madness arising out of intense creativity. A burning gaze alone revealed the creative fire that raged inside.

The Last Modernist

Beckett was the last of the great Modernists. His crucible and training ground was the Paris of James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, as well as Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. It is a great pity that Beckett never had the chance to meet the author of The Great Gatsby – that great work exploring the vacuity of capitalist aspirations. Fitzgerald matched him for pithiness, although he lacked the same profundity.

Those were heady days on the Seine, albeit Beckett was late to the party. He acted as a sort of amanuensis to Joyce, assisting him, in a way that is still unclear, in the completion of Finnegans Wake (1939). At one level he seems to have operated like a staff nurse, or what today we call a carer, leading Joyce – who was almost blind by that stage – to his final statement of total incomprehensibility, or brilliance, depending on your viewpoint.

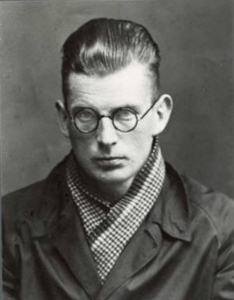

Photographic portrait of Samuel Beckett as a young man.

Yet Joyce’s torrent of words – full of richness and fecundity – the psychobabble of tongues and the fiddling with language, had a depressing effect on Beckett aesthetically. It is widely agreed that the latter’s early works, such as Dream of Fair to Middling Women (1932), More Pricks Than Kicks (1934), and Murphy (1938), did not scale the heights of his post-World War II masterpieces.

Similarly, I would argue the polyglot innovation found in Joyce’s final work is a form of literary escapism of limited relevance in this dark age of casino capitalism. Linguistic accuracy in marshaling facts is what I prize most highly, and Beckett delivered powerfully in this regard.

Beckett laconically described the relationship between the two literary titans in the following terms: ‘James Joyce was a synthesizer, trying to bring in as much as he could. I am an analyser, trying to leave out as much as I can.’[i]

Irish Bluffers

In my experience the Irish often display a tendency towards loquacity and linguistic chicanery. Unfortunately this provides scope for bluffers and often brings a resistance to facing up to the truth. Too often we take refuge in the deliberate self-deceptions of lyricism, or display a love of rhetoric and bombast that permits falsities.

As Seamus Heaney puts it in the poem ‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’ (1975):

O land of password, handgrip, wink and nod,

Of open minds as open as a trap,

Where tongues lie coiled, as under flames lie wicks,

Having said that Joyce in his early work, particularly Dubliners, captures some of the spoofing that is still a feature of life in the city, particularly evident politics, where the theatrical pseudo-debaters of hucksterdom are out in force.

Perhaps if we Irish were better listeners, and concentrated on using language with greater precision, we would not have dug ourselves, collectively and individually, into the awful hole we found ourselves in when the Banks crashed in 2007.

Uncharacteristically as an Irishman, Beckett is famous for the compression of language, which may explain his departure into French. Not a word is wasted in his writing; but like Joyce, words are sometimes re-invented or used in novel ways. Thus Beckett mangles and distorts language, stripping it to the bone to devastating effect, yet generally enhancing our understanding of it.

I cannot say I have enjoyed reading all of his oeuvre. The later works, particularly the plays, are heading towards the extinction of language itself, and offer an unsparingly bleak take on both art and human communication. I should add that all of this was in marked a contrast to the chatty and open person I encountered in Montparnasse.

However, the quartet of plays, Waiting for Godot, Endgame, Krapps Last Tape and Happy Days bear the unmistakable hallmark of genius, a commendation that should also apply to All That Fall, a play for radio memorably dramatized by Michael Gambon in 2013.

In my view the only playwrights his equal over the course of the twentieth century have been Eugene O’Neill for his A Long Day’s Journey into Night (which is also an exercise in Irish psychosis); Arthur Miller with Death of a Salesman and The Crucible; and perhaps David Mamet for Glengarry Glenn Ross; as well as the best of Bertolt Brecht. Indeed, Brecht was the only twentieth century dramatist of comparable stature, and even then he falls short in my view.

I would argue the only real modern rival – and that excludes the Bard of Avon – to Beckett’s Godot or Endgame is his near Irish contemporary Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. Surviving an Irish upbringing is never easy. It is perhaps no coincidence that Wilde died a broken man in Paris having endured imprisonment in Reading Gaol – immortalized in verse – his downfall coinciding with the Importance of Being Earnest becoming the toast of London.

Beckett preserved his genius to the end through an intelligent exile, the default option for Irish creatives and intellectuals. Yeats died in France. Beckett and Wilde in Paris. Joyce in Zurich. Most Irish writers get out Hibernia – ‘the land of winter’ which the Romans chose to steer clear of – if they can.

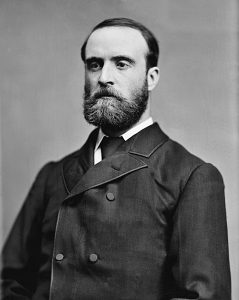

In my experience the Irish can be a deeply malicious lot. Anything goes and always has. Our downfall, collectively as a nation, lies in the art of cutting tall poppies down to size, and destroying national heroes. Thus the great nationalist leader Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-1891) was driven to an early grave for an affair out of wedlock with a married woman, Kitty O’Shea.

Charles Stewart Parnell, driven to an early grave.

Not all artists, it should be emphasised, lack wisdom and judgment. Beckett aged gracefully and is now buried in modest Parisian grave, where he is treated as a French writer and a hero of the Resistance during the Nazi occupation of France, where he demonstrated true courage.

The Novels

Moving on to the novels of Beckett, including the famous, or infamous, post-War trilogy of novels: Molloy (1951); Malone meurt (1951), Malone Dies (1958); L’innommable (1953), The Unnamable (1960). It is here we see a gradual dismantling and delimiting of language. In my view by the time of The Unnameable the artifice has gone too far and the conceit frankly tiresome.

My favourite novel, suffused with humanity, is Company (1980), which was part of an Indian summer of later works. Company, and indeed Worst Ward How (1983), also demonstrate the compression of language of the greater plays, as well as a playful sense of humour, something he is often unfairly accused of lacking.

Company is a lyrical and profound statement of his childhood in Leopardstown. Coincidentally, I was born just up the road from Beckett’s childhood home – not two hundred yards away – although not to the same conditions of privilege.

The compression of language at times in the novels is aphoristic and the statements on the human condition act like gelignite in their exactitude: ‘You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on,’ from The Unnameable, and in the and in the 1983 story Worstward Ho – ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’

There is an effortless font of ridicule in this. Woody Allen would have a field day, as he did in his essay on Irish writers.

In Our Times

I am not a literary critic and do not pretend to be one, so I am appropriating Beckett’s legacy for my own purposes.

It is clear to me that in our post-truth universe we require searing honesty rather than linguistic chicanery of a sort that provides us with ‘known unknowns,’ associated with the former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. We need to concentrate on that which matters, which is the truth, forensically researched and conveyed with precise language – and barbed if necessary – thereby providing an accurate portrayal of the human condition and the challenges we confront.

The extent to which Slavoj Zizek and Alain Badiou, the great Marxists or post-Marxists of our age, quote Beckett is revealing, although less surprising in the case of the latter given he is French. They quote Beckett to couple both absurdity and engagement, and to demonstrate the effective use of language.

Thus every lawyer committed to the truth, particularly a criminal defence lawyer, would do well to read and absorb Beckett in order to focus precisely on what is chosen to be said and, equally importantly, left unsaid. Beckett also helps us to recognise the nuances and tropes of language.

Moreover, a close reading of Beckett embeds a faculty for detecting bullshit: contained in his works you will find an unstinting focus on the essentials to human life.

What do you mean when you say this? What do you mean by what you say you mean? What do you mean by what you say or said or said then? Why did you do what you did? Who are you, and what do you say you have done?

Cross examination techniques are of course a poor excuse for a Beckettian aphorisms, but the importance of a literary appreciation in a lawyer should not be underestimated.

Samuel Beckett in 1977.

Swift Return

Other great Irish writers besides the Modernists are also relevant to our present dark age, Jonathan Swift above all else. The Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral received a disappointing sinecure after a controversial career as a journalist in London, where in carrying out his duties he alienated a large amount of influential people. The culmination of his rage arrives at the end of his life in the totemic work: ‘A Modest Proposal’.

The conceit of that piece, based on acute recognition of the Malthusian capitalism operating at the time, and contempt for absentee landlords, is that rather than letting the poor die in increments it would make ‘economic sense’ to eat their babies whole. This was the ultimate cost benefit analysis approach to law and economics, still evident in our dangerously commoditized world.

Finally, another Irish Nobel laureate, W. B. Yeats is also relevant in this regard, not for the Romantic murmuring of Innisfree, nor the more insightful political poems surveying the grubby inception of the state – ‘And add the halfpence to the pence. / And prayer to shivering prayer’ – but for the mystical poems from 1919 onwards, with their anticipation and exploration of the totalitarianism on the horizon.

Thus in ‘The Second Coming’ (1919) Yeats anticipates a world of immoderate extremism that has returned to haunts us.

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

he falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

So notwithstanding a tendency towards bluffing and linguistic chicanery, Irish writers have much to offer. Above all Beckett. He reminds us to be precise and exact with our words, while anticipating the age of extremes we have entered – a dark age of neo-liberal meltdown and capitalist excess, with fascism rearing its ugly head again.

Illustration by Malina/Artsyfartsy

[i] Mel Gussow, ‘BECKETT AT 75- AN APPRAISAL’, New York Times, April 19th, 1981, https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/19/theater/beckett-at-75-an-appraisal.html