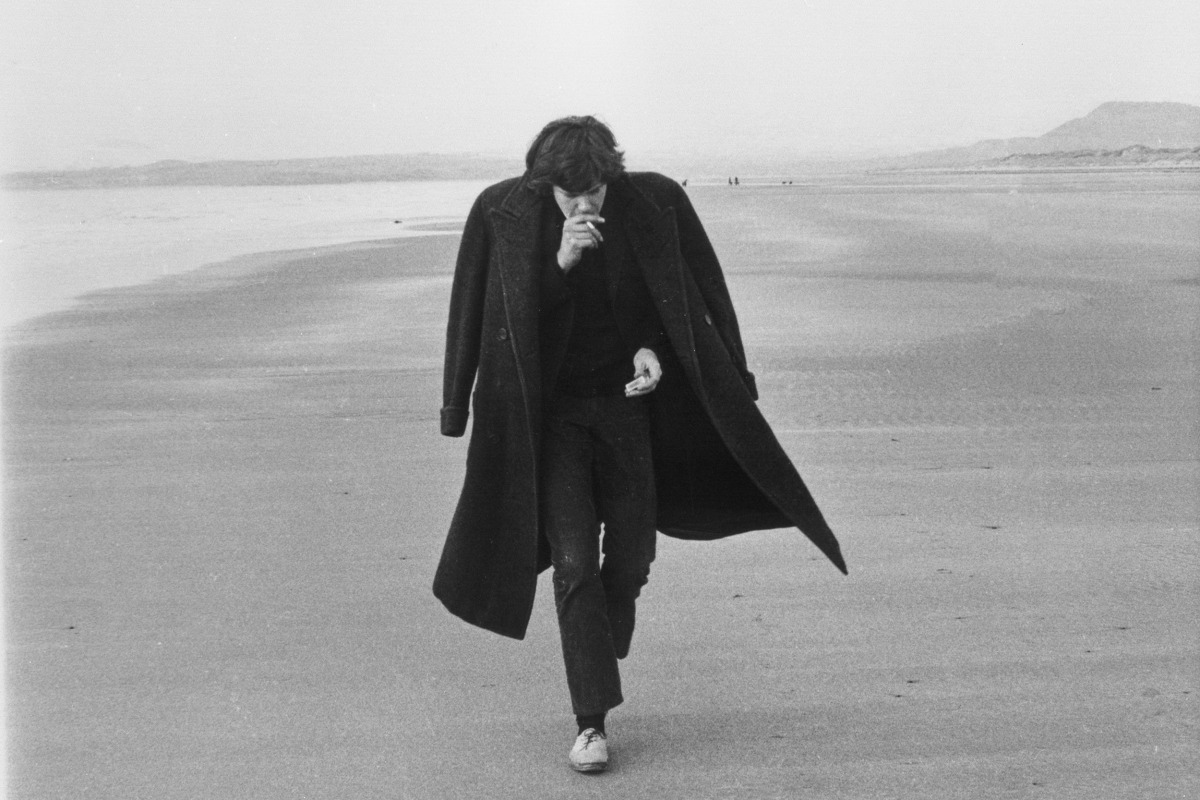

Julian Lloyd’s iconic portrait of Nick Drake now forms part of the U.K.’s National Portrait Gallery’s photographic collection. Lloyd’s friendship with the archetypal singer-songwriter, who died, tragically, aged just twenty-six in 1974, permits a rare intimacy between photographer and an elusive subject.

In some photos Drake looks to be at peace with himself and his surroundings, but in others of the doomed troubadour – featuring in Lloyd’s new exhibition running in the Horse Gallery, Dublin 1, from July 6th to July 17th – we find a less playful figure, with Drake brooding beneath a heavy coat on a Welsh beach, inhaling urgently.

Nick Drake, Selbourne 1968. © Julian Lloyd

Lloyd says Drake was “a nice, easy going, companionable man, very private, but not particularly buttoned-up. Obviously he became ill – a cruel mental illness which locked him up and made him miserable. Nick was just one of the gang, but obviously he had a talent.” The budding artist, who only achieved posthumous fame, was “happy to play in front of a few of us in a room. Never anything boastful or show-offy about him.”

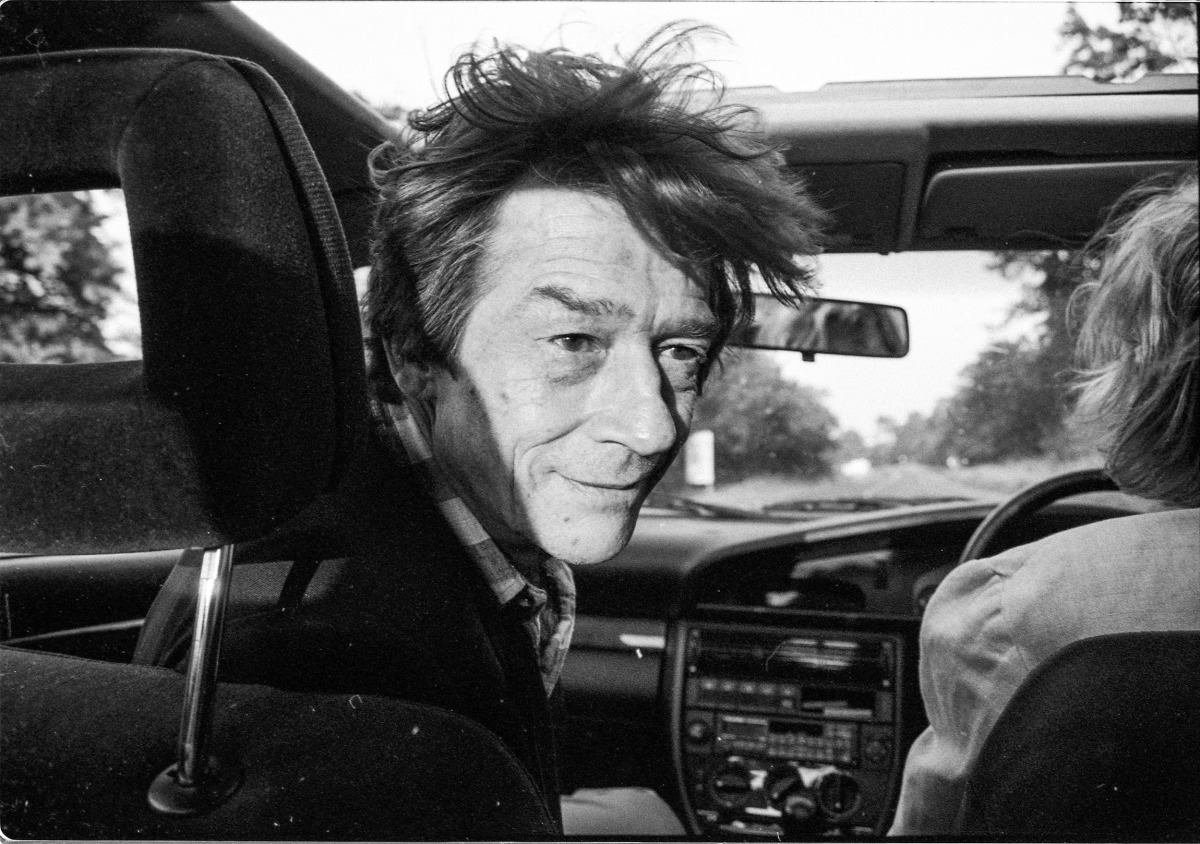

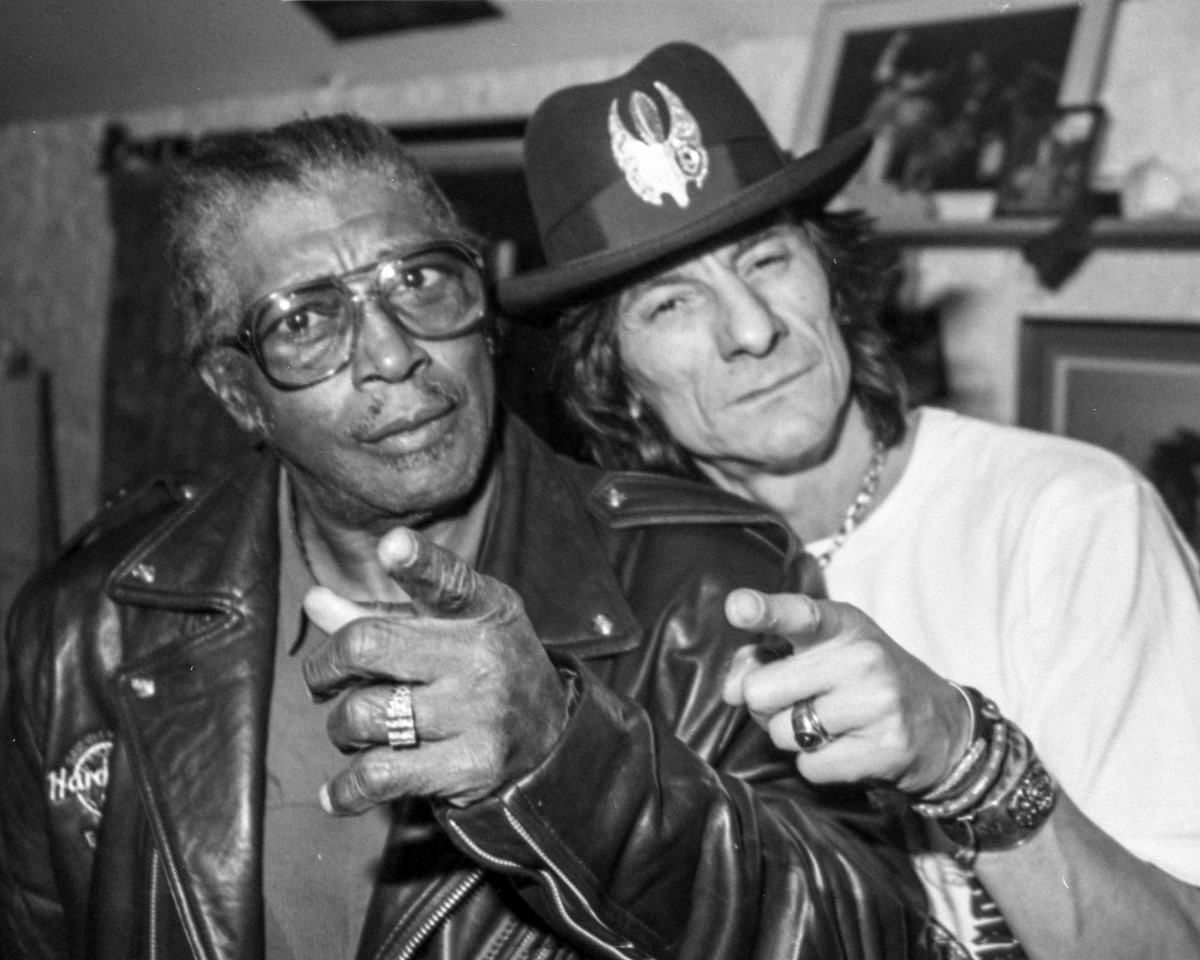

Lloyd claims that it was “pure luck and happenstance” that brought him into the same social circles as figures such as Drake, and later, after he moved to Ireland – to work with horses – musicians such as Ronnie Wood and Dolores O’Riordan, along with actors such as John Hurt.

Bo Diddley and Ronnie Wood, Sandymount House 2002. © Julian Lloyd

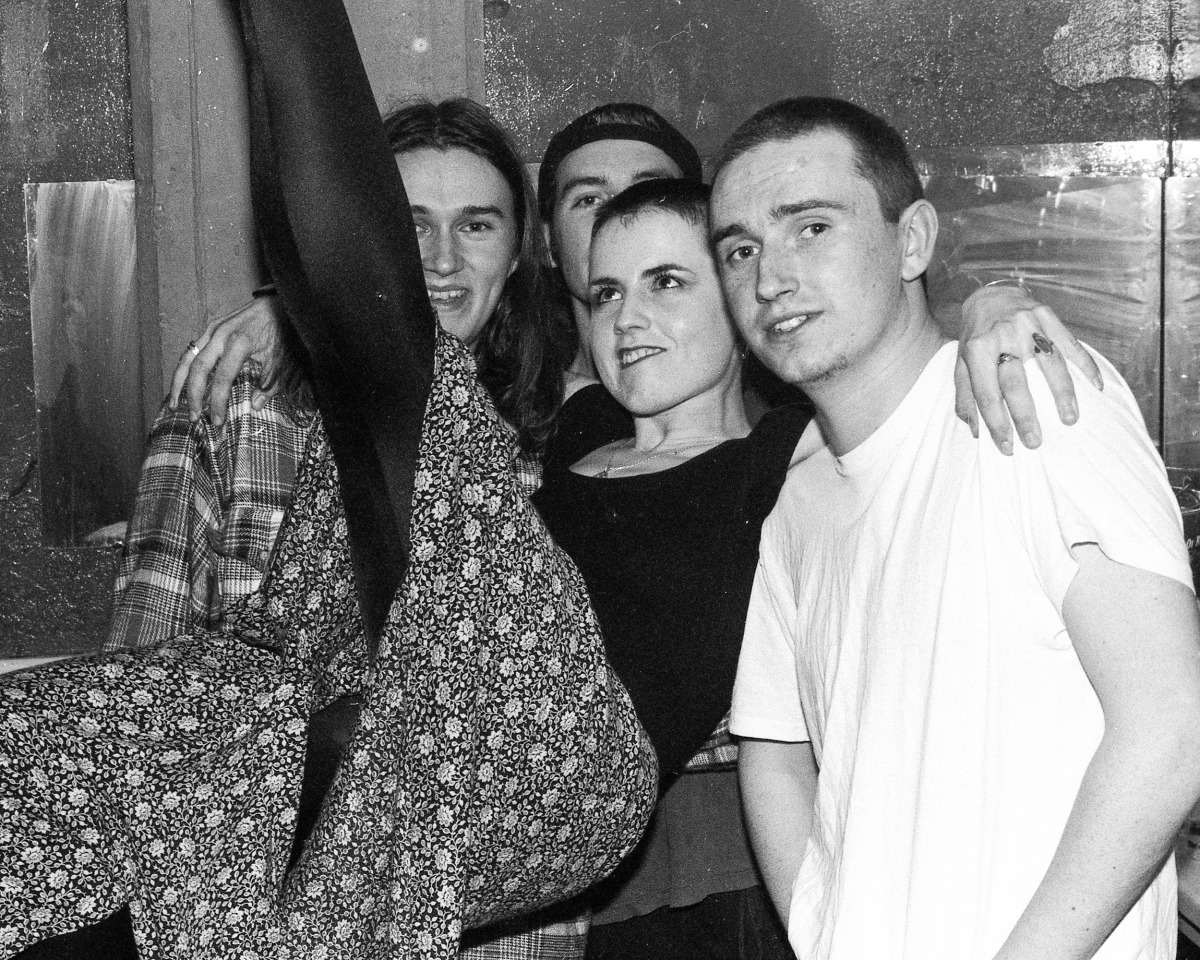

Despite many of his subjects being celebrity figures, there is a lightness to the work. You really get the impression that Julian Lloyd was simply a photographer among friends.

Crystallising Memories

Julian Lloyd clearly possesses a keen eye for the poignancy of a fleeting moment in time, crystallising memories, whether at a carefree party or even outside a funeral, which is the hallmark of great photography, and art more broadly. Choosing when to take out the camera and start shooting is a fraught exercise, as a subject may recoil or put on a false persona before the lens. Lloyd seems to have a knack of timing this to perfection.

Dolores Oriordan and the Cranberries, Tivoli Theatre, Dublin, 1993. © Julian Lloyd

Lloyd is not in the least bit precious about his photography, confiding that on occasion he is not averse to having a few drinks at a party, and allowing auto-focus to prevent any mishaps. Nor does he feel threatened by the ubiquity of smart phone photography, recalling the insight of the American photographer David LaChapelle, who put it to an audience that while everybody in the world has access to pen and paper, few writers attain the level of Shakespeare.

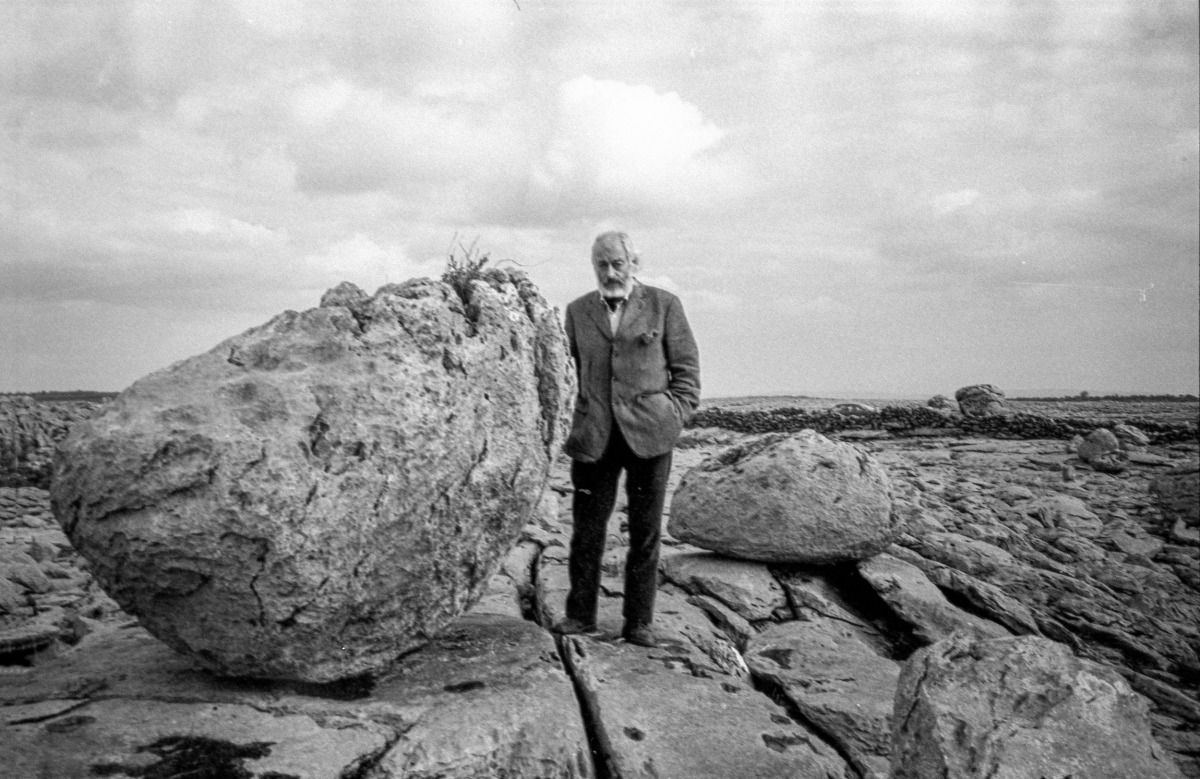

J.P. Donleavy, The Burren. © Julian Lloyd

He also dismisses the idea that photographers conform to a particular personality type, recalling meeting with “ebullient, chatty, noisy photographers, and also furtive ones, who creep around in corners.” His own work has been in “fits and starts”. He was pretty broke for periods, and had no camera to work with after a theft for some time.

- John Hurt, driving home from drinks

- with Marianne in the Shell Cottage. © Julian Lloyd

Hippie Trail

Apart from the glamour of his rock ‘n’ roll and aristocratic subjects, we also find an abiding love for Ireland in the collection, especially the characters he encountered along the way, such as the parking attendant at the Cliffs of Moher who sold tin whistles on the side.

After leaving school he first plied his photographic trade for a local newspaper in Northumberland near the English-Scottish border, where ships would occasionally pull in undetonated World War II mines for him to photograph.

He then moved to ‘Swinging Sixties’ London, where he secured a job in a photographic studio, and met his future wife Victoria, whose sister was going out with Eric Clapton at the time. George Harrison was also on the scene.

There reached a point, however, when, like other hippie idealists, he wanted to move to the country. Back then “people would set off in barrel topped wagons.” He and Victoria followed suit, found one for themselves and purchased a mare to take it from Swindon to Somerset.

This proved a life-changing experience. Despite no family or other background with horses, he grew fond of the mare and “the whole relationship with horses.” Later he found a job with a horse dealer, learning the business “from the ground up.”

Boxer, His final winter, Leixlip, 1989. © Julian Lloyd

Lloyd’s unusual hippie trail eventually brought him to Ireland. This was he says “a very vivid experience.” He and Victoria found “a very different culture living in Ireland than it was in Britain. It was very, very attractive.”

In 1975 he came to work for Tim Rogers in Lucan in county Dublin, who had, he says “the best stallion operation in Europe at the time.” It would be over forty-five years before he finally returned to the U.K.. He has recently moved to live in Shropshire near the Welsh border, where Victoria’s family is from.

He recalls a friend, Sean Doyle saying to him that “to succeed in life you must have an unfair advantage.” But unlike the relatively easy world around his photography, Lloyd enjoyed no unfair advantage when it came to horses, making it “very, very difficult.” It was a seven day a week job, to which he “gave it everything” and possessed “the zeal of the convert”. Nonetheless, he spent “plenty of years skint” during a time when it was “very, very hard to make a living.” If photography was a playful mistress, the breeding and raising of horses was a demanding master.

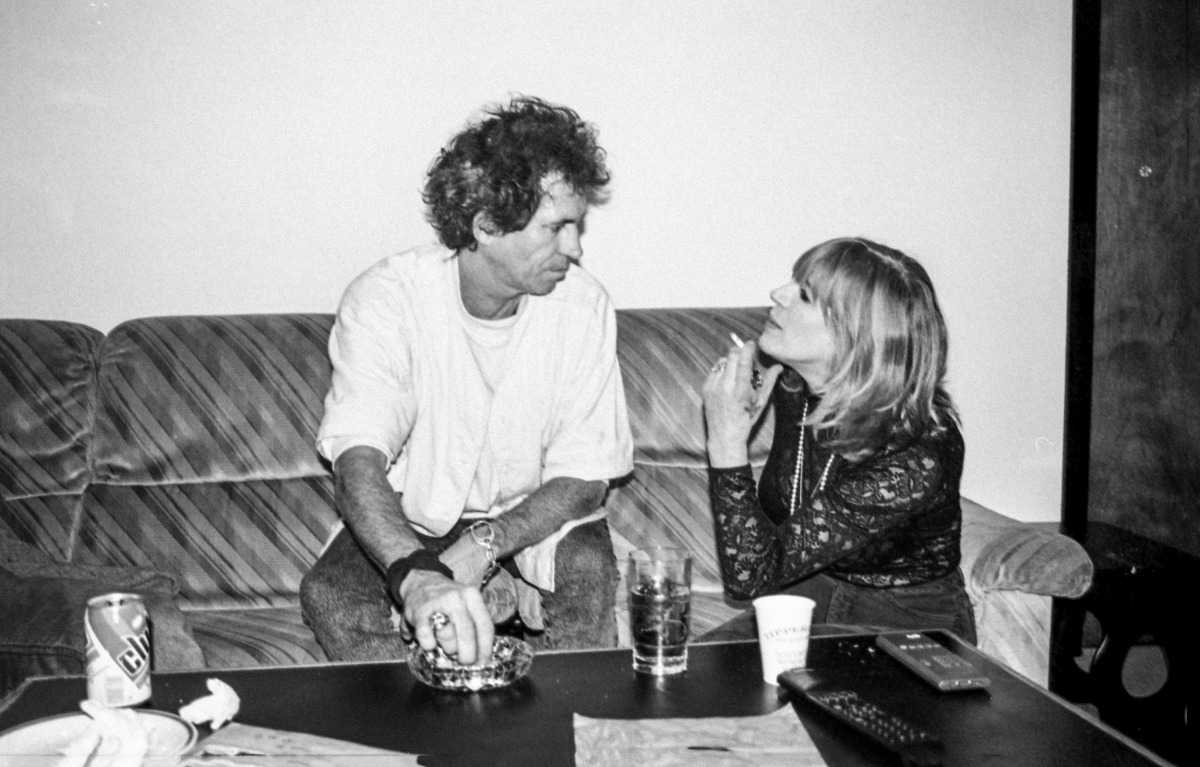

Mirianne Faithfull and Keith Richards, Windmill Lane Studios, Dublin, 1994. © Julian Lloyd

Safe Haven

Lloyd describes Ireland as “a safe haven” – away from a prying media – for many of the English musicians and other artists who took up residence here from the 1970s. Some like Marian Faithfull found a more receptive audience for their work.

Julian Lloyd’s photography captures that carefree world, which existed, unimpeded, alongside surviving remnants of a peasant society, which also features in his work. It was perhaps to his great advantage that he did not depend on photography for an income, but could instead indulge a passion in intimate settings, where he could blend in seamlessly with the crowd.