We all see things with different eyes and it gets you nowhere hoping that one in a thousand will see things your way.

J. L. Carr, A Month in the Country (1980).

In his droll 1999 essay, ‘Reader’s Block’, Geoff Dyer describes suffering from what he calls a creeping condition whereby he finds himself staring blankly at his bookshelves noting all the books he hasn’t read and thinking “there’s nothing left to read”.

Such was Dyer’s malady that even so-called “quality fiction” seemed a waste of time. He was forty-one. Back in his twenties he had imagined he would spend his middle age reading the books he didn’t have the patience to read when he was young. But it was not to be, and now he found himself resigned to leafing through the pages of the in-flight magazine when traveling abroad rather than reading the books he brought for the journey.

Being roughly the same age as Dyer, I identified wholly with his piece back then, and in a way still do. But my malady, my “reader’s block”, is more specific: it was fiction that got on my nerves at the onset of middle age, and years later it still does. I don’t suffer from reader’s block, but rather fiction reader’s block, or to be more precise, novel reader’s block.

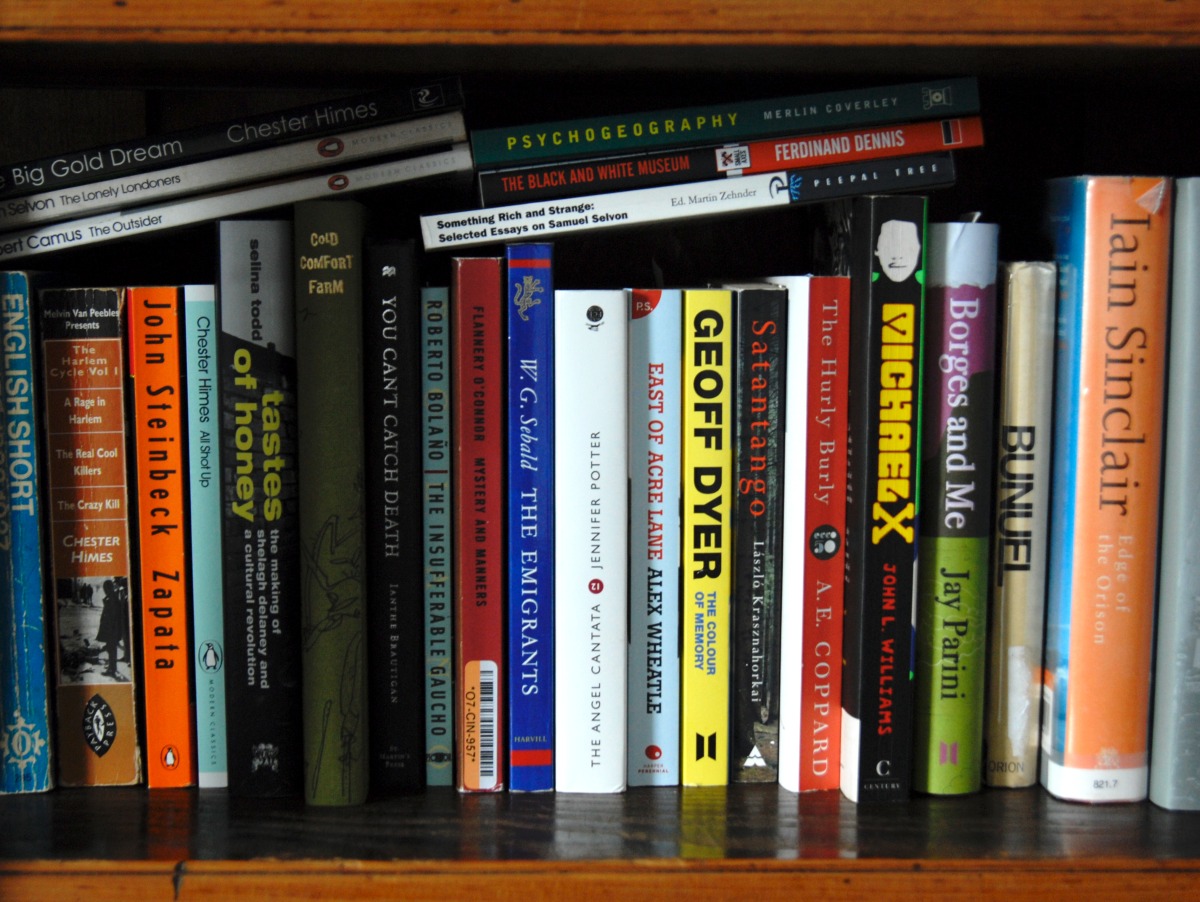

Occasionally some fiction does slip through the net. Jennifer Potter and Ferdinand Dennis are on my bedside table alongside the handful of old favourites that I occasionally revisit: Sam Selvon, Chester Himes, Shelagh Delaney, Stuart Dybek, W.G.Sebald and Ann Quin. But it is to non-fiction that I mostly turn and have done for over twenty years.

Currently I’m engrossed in Patrick Wright’s monumental The Sea View Has Me Again, an extraordinary telling of the German writer Uwe Johnson’s lost decade on the Isle of Sheppey. Johnson drank himself to death in bleak surrounds of the Sheerness Sea View Hotel in the 1984.

But what is this affliction? It’s not laziness or distraction, nor the inability to concentrate on anything that doesn’t offer immediate gratification. Patrick Wright’s multi-layered opus is a densely packed seven hundred page micro-history of both Sheppey and Uwe’s self- exile, and is not remotely daunting. Likewise, Speak, Silence, Carole Angier’s detailed study of Sebald’s life and work comes in at over six hundred pages, and is not a page too long in my view.

In interviews the highly-regarded contemporary writers Kevin Barry and Rob Doyle can be interesting, but the preoccupations they display in their fictions are those of young men and are of no interest to me at all at my stage in life.

Now to be sure, I’m of the wrong demographic for Sally Rooney or Nicole Flattery, but I can’t hack the imagined worlds of the Colm Toibins or John Banvilles either – in form and content they’re just not my cup of tea. It is of course a question of taste, but I can’t abide the narrative armature of story-driven literary fiction with those wretched character arcs – as Shakespeare fully understood, people do not change.

Mark Venner evokes 1970s England, a time of Bronco toilet rolls and King Crimson albums, when Jack Russell terriers still snapped at the coal man's feet.https://t.co/SPLJSrswV0@broadsheet_ie @IlsaCarter1 @EdwardClarke20 @hisonlysonnet @wadeinthewate11 @NMcDevitt @FutureVisions5

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) January 14, 2021

My inability to read literary fiction doesn’t bother me, and I don’t need my ideas of the world to be shaped. My view of the world is fully formed and doesn’t need to be textually generated or reinforced.

But I am a reader, and always have been, even though I grew up in a non-reading household. Even when I was boy, I knew where to look for my reading material. I was a discriminating reader. As an eleven-year old I knew Edgar Allan Poe was good and H.P. Lovecraft was bad. I could see that, unlike Henry James, William Golding wrote in clear, straightforward prose to elucidate complex themes.

As a young adult in the counter-culture era of the late 60s, I recognized that Mervyn Peake was a singular talent and a great stylist, and that Tolkien was a dull and pedestrian writer. Jean Cocteau, even in translation was great and Burroughs’ debut Junky/Junkie was a fine example of taut, economical writing that surpassed his later experimental fiction.

Underlying Mark Venner's ongoing project is to take a personal history with a strong sense of place and to overlay this with pop cultural references.https://t.co/nU9veqVQ3Y@broadsheet_ie @corourke91 @danwadewriter @FutureVisions5 @itsmybike @Bate_Kevin

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 3, 2021

Recently I was chatting with an old friend. He’s an exiled Corkonian living in Italy, and an erudite man of letters. We spoke about my aversion to fiction and he echoed my sentiments. Somehow our conversation turned to Flannery O’Connor. I’m an admirer of her short fiction but now find myself confused and a little wary of her after the revelations in 2014 of the racist views expressed in her correspondence.

My friend had never read O’Connor. Could O’Connor be saved from herself? I don’t have the answer, but her fiction can stand alone. I told my friend how in the 1950s reviewers were constantly vexed by her characters’ lack of interiority. My friend lit up at this: “I like the sound of that! I can’t stand being told what characters think and feel. I just want a description of where they go and what they do.” Simply and succinctly put.

In The Lonely Voice, Frank O’Connor wrote that for some reason he could only guess at, “the novel is bound to be a process of identification between the reader and the character. One character at least in any novel must represent the reader in some aspect of his own conception of himself”.

It is this process, embedded in the mechanics of fiction, of identification and absorption into a psychological world, that in time becomes for me recognizable and tedious. So maybe it is a case that non-fiction – and certain rare types of fiction that bypass identification in favour of evocation of a world and its details – doesn’t use itself up in the telling. It stays with us. And so, in the meantime and undoubtedly for the rest of my life, I will follow my instincts, knowing that non-fiction will more likely give me what I want.

Feature Image: Mark Venner