Sucked in by day-to-day dramas, or absorbed by the most closely studied pandemic in the history of medicine, the mental space to muse idly is severely circumscribed. But we may find a portal, removed from the daily thud of mortality lists and the slow grind of lockdowns, to raise the spirit. Art is more important than ever at this time.

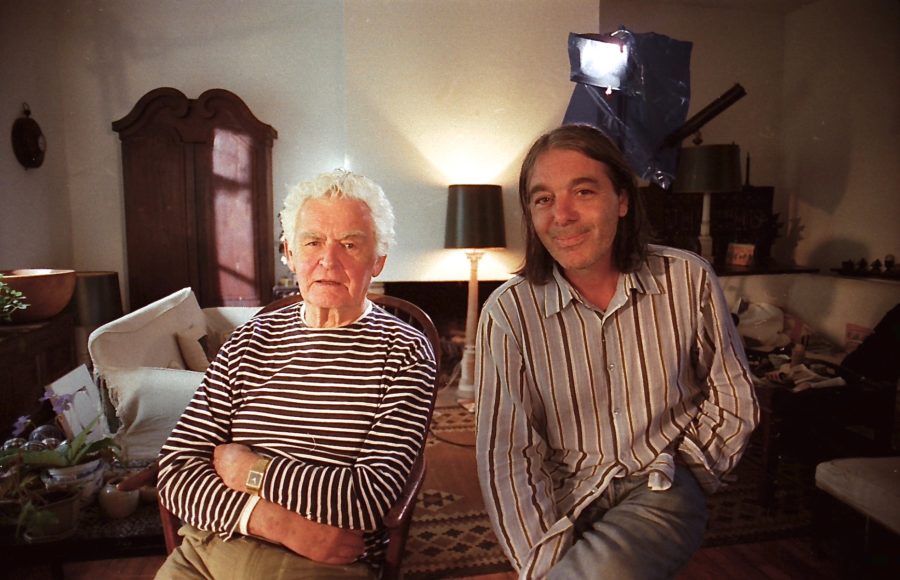

Shamefully, I had hardly engaged with the great Irish artist Patrick Scott before watching Sé Merry Doyle’s vital documentary ‘Patrick Scott: Golden Boy,’ from The Loopline Collection stored in the Irish Film Archive.

This grand old man of Irish art passed away in 2014, aged ninety-three. Doyle’s documentary provides a vital record of an artist whose work is infused with a tranquillity and balance, seemingly derived from lifelong interest in Zen Buddhism. It is an influence apparent in mesmeric meditative tables skillfully integrated into the film.

Doyle’s intimate portrayal takes us into the artist’s home, which he shares with an elegant black cat. ‘I’ve never got a cat, they’ve always got me,’ Scott reveals as the feline owner brushes softly against his forearm, whereupon he receives a loving stroke. Although the speech is slowed by age, calm deliberation is still on display, and evident throughout his oeuvre too.

The documentary takes us to Scott’s family roots on a substantial farm in Country Cork that is still occupied by a relation. The ‘Golden Boy’ came from a comfortable Protestant background, before boarding school at St Columba’s College in the Dublin mountains.

The turbulent conditions of the 1930s and 1940s, including the Economic War, which almost bankrupted his family, and frustrated a wish to train as an architect – the standard career opportunity for anyone of an artistic bent at the time – before the intercession of a family friend allowed him to begin his studies in UCD.

Patrick Scott spent fifteen years working as an architect under the great Michael Scott, who was no relation. Although it may not have been his first love, the cross fertilization that occurred seems to have been mutually beneficial.

Among the projects that Patrick worked on in that period was the Busáras building on Store Street in Dublin 1, heavily influenced by Le Corbusier, still considered one of the most significant pieces of architectural heritage in the city.

Busarus in Dublin.

The one-time architect bemoans how the building is ‘nothing but a departure shed now;’ although the camera identifies the yellow mosaic dome that is easily forgotten in the general hustle and bustle.

The young architects had imagined a multi-purpose hub of commercial activity and civic interactions. Indeed, there is still a roof-top restaurant space that reminded me of a similar venue in Lisbon, but which, according to Scott, has never been used as anything other than as a staff canteen. Can something be made of this delightful venue in the future?

In parallel with his architectural career, which he was finally able to walk away from in 1955, once he was able to earn a decent living through selling his art, Patrick Scott was finding his way as a painter. He embraced an array of styles and motifs, including using wet canvasses and whips for brushes, as well as the gold enameling that gives this work an iconic impression, which continues to inspire graphic designers today.

There is also an important discussion of the White Stag movement in Irish art, which developed among British artists that moved to Ireland in 1930s and 1940s. Basil Rakoczi and Kenneth Hall developed a dynamic focus of energy that had a profound effect on artistic practice in Ireland, including on Scott who joined the group.

In 1960 Patrick Scott became the first Irish artists in thirty years to have their work exhibited at the Venice Biennale. It is indicative of the status of art, and artists, in Ireland at the time that he had to pay his own way to attend the occasion, as well as for the catalogue and press cuttings. The skill of Doyle’s documentary filmaking is to reveal these kind of details. It might bring consideration to the plight Irish artists today, who contend with a high cost of living and low funding by comparison with other European countries.

WATCH THE FULL DOCUMENTARY HERE FOR FREE