I was briefly a Professor of Law and International Relations at the Anglo-American University in Prague, near where the Jewish, German-speaking Kafka was born and raised.

Before arriving, I had acquired a superficial knowledge of the main sights, which are somewhat deceptive and largely unrewarding in that rich tapestry of a city – of which it has been written that by the end of the nineteenth century, ‘deprived of political significance, abandoned by the aristocracy, commercially and industrially backward, [it]had the feeling of an industrial city, suffused by the elegiac atmosphere of a glorious past.’[i]

Apart from heavy industry – the Czech Republic retains a glorious rail infrastructure – the Prague of that period can be likened to Dublin in the wake of the 1801 Act of Union, after which it fell into terminal decline. And, indeed, Arne Novak’s description of the Czech national temperament might apply to the Irish literati: ‘continually fluctuating between two poles: on the one hand a self-righteous over-estimation of everything native, with a stubborn clinging to ancient privileges; on the other hand, impatient curiosity about the latest foreign literary fashions, and a readiness for slavish imitation.’[ii]

Nonetheless both nations, dominated by two cultural blocks – the British Empire and the European Catholic Church in the case of the Irish; Germany or Austria and Russia or the Soviet Union in the case of the Czechs – have produced literary titans, who have railed as much against native subservience as against colonial usurpers.

Thus, in James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) Stephen Daedalus calls himself ‘the servant of two masters,’ indicting ‘The imperial British state’ and ‘the holy Roman catholic and apostolic church’, while Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk (1923), also written in the shadow of the Great War, remains one of the great anti-war novels.

In this article I focus on two Czechs authors, the aforementioned Franz Kakfa, and Milan Kundera whose response in different epochs, to imperialist oppression, provide important insights for contemporary challenges.

Prague Spring

It is in Prague’s shadowy labyrinth of side streets, with a rich diversity of specialist shops and bookstores – fast disappearing from other urban conurbations – that one finds the real gems. Apart from brief excursions, my knowledge of the Czech Republic had mostly been gleaned from cinema and literature of a society that has endured the evils of both Nazism and Communism, while managing to preserve its civilisation.

This rich inheritance can be found in the gloriously satirical 1960s films of Milos Foreman such as ‘The Fireman’s Ball’, which provides an anatomy of the soul of man under Communism.

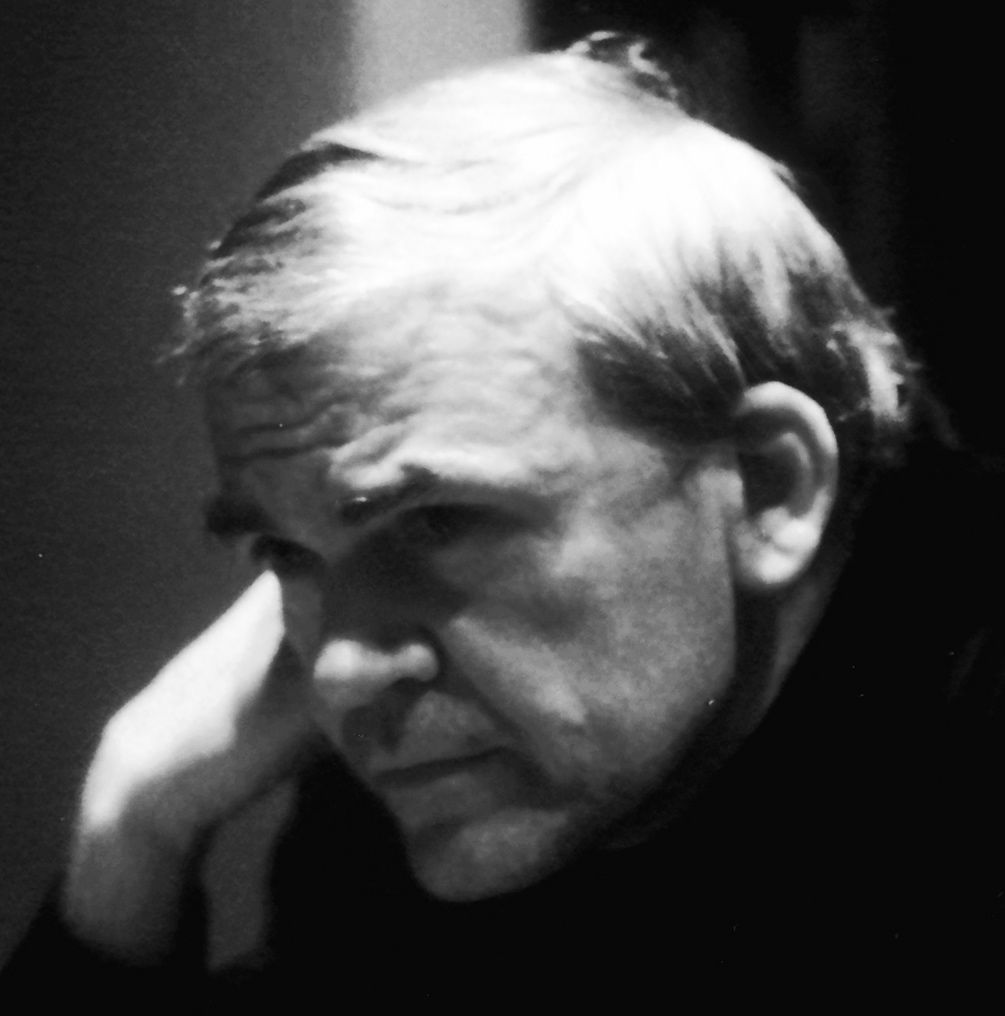

Milan Kundera 1929-

More importantly, there is the contemporary work of that most deserving living candidate for the Nobel Prize, the Czech writer, Milan Kundera. His novels are a crash course in uninhibited eroticism, vastly different culturally to an Irish sensibility. They offer textbook exercises in a form of European decadence alien to the repressive Irish mindset, and our smutty obsession with sexual activity – not undivorced, I believe, from the extremities of sexual perverted crimes that dominate newspaper headlines in an increasingly hedonistic society.

Kundera’s novels, in translation at least, are written in an elegant lapidary style. There is a lot of dark laughter in those books, not unlike the Irish lachrymose sense of humour and despair, found in Flann O’ Brien especially.

One such example is Kundera’s exposition on litost, ‘an untranslatable Czech word’, in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting:

Its first syllable, which is long and stressed, sounds like the wail of an abandoned dog. As for the meaning of this word, I have looked in vain in other languages for an equivalent, though I find it difficult to imagine how anyone can understand the human soul without it…

Kundera expands on its meaning by way of anecdote.

She was madly in love with him and tactfully swam as slowly as he did. But when their swim was coming to an end, she wanted to give her athletic instincts a few moments’ free rein and headed for the opposite bank at a rapid crawl. The student [the boy]made an effort to swim faster too and swallowed water. Feeling humbled, his physical inferiority laid bare, he felt litost. He recalled his sickly childhood, lacking in physical exercise and friends and spent under the constant gaze of his mother’s overfond eye, and fell into despair about himself and his life. They walked back to the city together in silence on a country road. Wounded and humiliated, he felt an irresistible desire to hit her.…and then he slapped her face.

His most prescient points concern historical amnesia and the onset of tyranny. As he put it: ‘The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.’

Forgetting

The internet and social media are fast becoming a tool of forgetting or non-remembrance through the deluge of unfiltered information. The greatest area of amnesia is the subject that Milan Kundera dedicated his career to preserving, namely the horrors of Communism, which finds strange echoes in our current transition from neoliberalism to neoconservatism.

The ‘Liberation’ of Prague by Soviet Forces in 1945.

Kundera described what passed for public discourse under Communism as political kitsch in his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being. This emanates from an aesthetic ideal ‘in which shit is denied and everyone acts as though it did not exist’. ‘Kitsch’, he argued, ‘is the aesthetic ideal of all politicians and all political parties and movements.’

It is the dream scenario of the spin doctor where the press is utterly compliant. He gives the example of politicians kissing babies as an obvious expression political of kitsch.

In Kundera’s view political kitsch is not dangerous in itself, and most politicians cultivate a clean-cut, artificial, image. The real danger lies in totalitarian kitsch such as that encountered by the character of Sabina, who recalls the Communist parades of her youth, which projected an idealised vision of the worker removed from the corruption, suspicion and cruelty that infected her society. Indeed, it was said in Czechoslovakia that love for one’s family required theft in the course of one’s professional life.

Kundera contrasts what looks suspiciously like de-platforming, or cancel culture, with the plurality of voices that he believed still lay in Western democracies:

Those of us who live in a society where various political tendencies exist side by side and competing influences cancel or limit one another can manage more or less to escape the kitsch inquisition: the individual can preserve his individuality. The artist can create unusual works. But whenever a single political movement corners power, we find ourselves in the realm of totalitarian kitsch.

It begs the question whether the Internet has reawakened this “totalitarian kitsch.”

Air-brushed from History

In the same work Kundera describes a moment in Prague in 1948 amidst heavy snow in which the bareheaded Communist leader Klement Gottwald, while giving a speech in Wenceslas Square, was handed a hat by his comrade Vladimír Clementis. Four years later Clementis was purged – charged with treason on trumped up charges and hanged. The propaganda section literally airbrushed him out of history by removing him from the photograph that is the title image for this article. Ever since Gottwald has stood on that balcony in splendid isolation.

Where Clementis once stood, there is thus only a bare wall. All that remains of him is the cap on Gottwald’s head. Similarly, to get rid of an enemy today, you do not have to prove anything against them. Instead, you use the internet or family courts, or indeed a compliant media, to generate conflicting accusations and contradictory data. You sow confusion to elevate hatred and fear until that enemy is either banned from social media, their history re-written or erased from the minds of millions through smear, disposal and, in fact, apathy.

If the struggle of man is the struggle of memory against forgetting, as Kundera put it, then we have in the cacophony of the internet a vast machine for forgetting. One that is building a new society upon the shallow, shifting sands of what Gore Vidal described as the United States of Amnesia.

Of huge relevance to our times, Kundera said:

The first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory. Destroy its books, its culture, its history. Then have somebody write new books, manufacture a new culture, invent a new history. Before long that nation will begin to forget what, it is and what it was. The world around it will forget even faster.

It is like a clairvoyant presaging our times. A pre-Facebook comment on our age of gnat-like attention spans. A world of amnesia and the distortion of history; of canned laughter and forgetting.

Václav Havel in 1965.

Kundera’s only modern contemporary intellectual equal, the former President of the Czech Republic Václav Havel issued a similar warning in his seminal political essay, ‘The Power of the Powerless’ (1978). The then dissident playwright and philosopher argued that empowerment requires us to ‘live in truth,’ which means facing up to the uncomfortable reality that we are not solely victims of the political and economic order we live under, but sometimes also enablers who play into its myths and cover up its lies.

We turn the lies into truth and come to believe it is the only way to get through; the only way to survive in what we are told again and again is a ‘dog-eat-dog’ world. In a reappraisal at the end of his tenure, Havel observed how neoliberalism had created similar social dynamics to Communism.

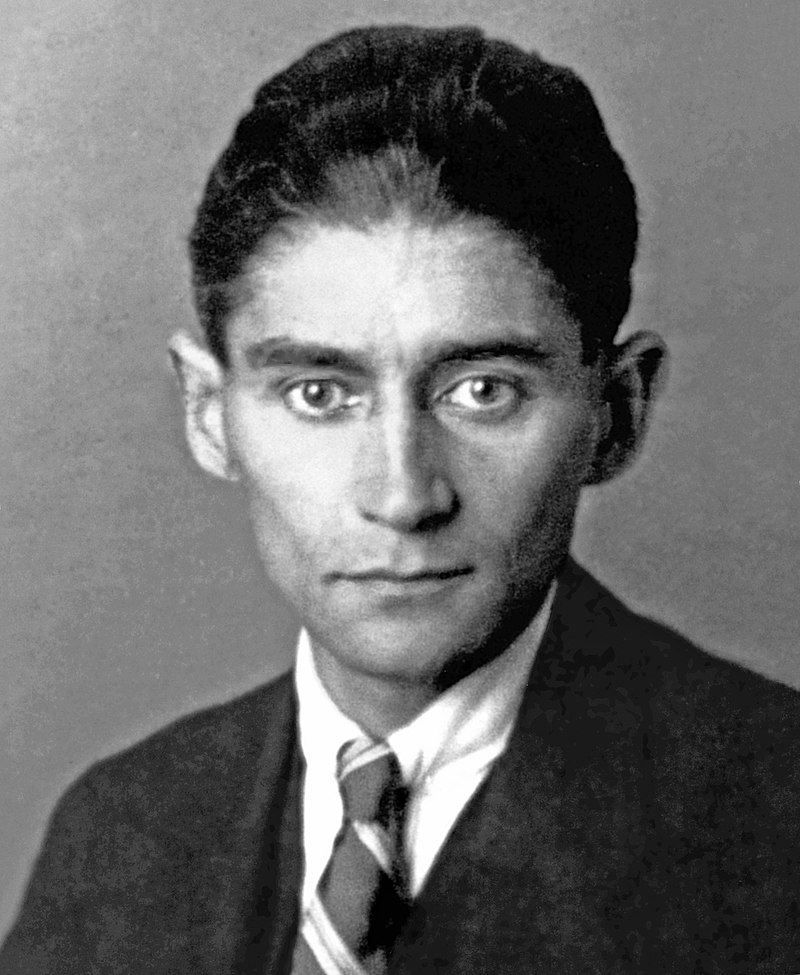

Franz Kafka as a young man.

Kafkaesque

Despite writing in German, Franz Kafka reigns supreme as the writer par excellence of Prague. He now resides like an all-enveloping spirit in Prague. In the Jewish quarter there is a rather modernist statue of him; his visage and silhouette adorn mugs and t-shirts in every tatty tourist shop. There is also an expensive and rather uninformative Kafka Museum, and a bookshop in his name.

Above all else, there is his former house near the Castle, down from the narrow Jewish mile road. His house, now converted into a museum, is not that dissimilar to the two bedroomed artisan houses near the Four Courts in Dublin.

Apart from writing in German, Kafka was Jewish, giving him an outsider status in the Czech Republic; historically an uncomfortable position – though not anything like as bad as it was in Poland – to be in.

While living in Prague, it was an immense surprise to find how Germania had been expurgated from Czech culture after the War. The Czechs now speak English primarily, and Russian occasionally, despite being enveloped by German speaking territories. Still, they venerate Kafka and why not.

Legal Conformism

Part of my own adoration of Kafka comes from training to be a lawyer, and an expression used in a case that has dogged and at times unsettled my career: Gilligan v Ireland. (1997).

The expression I used a ‘Kafkaesque situation’ arrived impromptu to describe what was happening, although I was aware that other Irish judges, particularly Cathal O’Dalaigh had used a similar phrase.

In a legal context the expression conveys a situation of labyrinthian complexity, absurdity, and perversity: one where the law is traduced by procedure and injustice and has become – to use common parlance – an ass.

Franz Kafka did not find the study of law to be an edifying experience. Indeed, according to one account cited by the legal scholar Robin West, he found it ‘had the intellectual excitement of chewing sawdust that had been pre-chewed by thousands of other mouths.’

In Authority, Autonomy, and Choice: The Role of Consent in the Moral and Political Visions of Franz Kafka and Richard Posner (1985), Robin West argues that in Kafka’s world law is alienating and excessively authoritarian, exerting in people a craving for conformity. Students have an urge to conform or obey the law. She argues:

Kafka’s world is populated by excessively authoritarian personalities. Kafka’s characters usually do what they do – go to work in the morning, become lovers, commit crimes, obey laws, or whatever – not because they believe that by doing so, they will improve their own wellbeing but because they have been told to do so and crave being told to do so.

Plaque marking the birthplace of Franz Kafka in Prague.

She contrasts this negative view of the law, with the view that it facilitates the maximization of one’s own welfare, which is presented by the right-wing law and economics scholar Richard Posner:

Whereas Posner’s characters relentlessly pursue autonomy and personal wellbeing, Kafka’s characters just as relentlessly desire, need and ultimately seek out authority.

Further, West points out that although both Kafka and Posner see people as consenting to the various transactions they enter, for Kafka, such consent can lead to humiliating and degrading employment, sex and even death. This point is not expressly made by West, but this may be familiar to readers of The Trial. For Posner, such consent is rational and self-fulfilling. For Kafka, such consent leads to victimization.

West thus posits a conclusion from Kafka on consensual market transactions which is far from positive:

In all these market transactions – commercial, employment, and sexual – Kafka portrays one part consenting to a transfer of power over that party’s body, and in each instance the transfer, although consensual, is horrifying. In none of Kafka’s depictions does consent entail an increase in wellbeing … The participants are often motivated by a desire to submit to authority, not to enhance autonomy, and in each case, the authoritarian relationship they create proves to be a damaging one.

Moreover, West examines the question of consent to law in Kafka. According to Posner, people consent to legal imperatives that are wealth maximizing. According to Kafka, they consent to impersonal state imperatives not because of wealth maximization but out of a deep-seated desire for judgment and punishment. Or one might add compliance.

‘The Judgment’ and ‘The Refusal’

Thus, in Kafka’s short story ‘The Judgment’, a son submits to death by drowning as his father has decreed. And in another short story ‘The Refusal’, the townspeople obey the colonel in charge of the town because authority has ‘just come about,’ and submit to his various denials of their petitions.

The most dramatic example of this submission to authority is of course in The Trial, where Joseph K is arrested without having ever done anything wrong. He never learns the nature of the charges laid against him; he is arrested but not imprisoned; interrogated but never forced to appear; yet in time he passively accepts the jurisdiction of the court and the law’s authority, which results ultimately in his own death sentence.

Finally, West relies upon the short parable ‘The Problem of our Laws’, in which Kafka informs us that law is ultimately sustained, not by force but by the craving of the governed for judgement by lawful, noble authority. It is this human craving, even more than the urge of the powerful to dominate, that sustains the illusion of certainty, fairness, generality, and justice.

In conclusion, West derives the message from Kafka that:

Our tendency to legitimate lawful authority – to give our hypothetical consent – may have good or evil consequences, depending upon the moral value of the legal system to which we have submitted and the moral quality of the relationship between state and citizen that our consent nurtures.

Scepticism Towards Authority

How much of this is of jurisprudential or indeed morally significance? First, it confirms an innate prejudice of mine which is to be at the very least sceptical of authority. Deep scepticism. Far too many people who have had no interaction with authority figures, such as police officers or indeed judges, are inclined to defer to their wishes and take what they say at face value. My experience as an Irish barrister has engendered in me the opposite instinct. Always confront, challenge authority, and never commit the cardinal error of submitting to the edicts or wishes of authority.

Also, ask who is in authority and why they are there? Who appointed them and what agenda do they serve?

Kafka also touches on the way procedural tangles and processes often run contrary to that elusive concept of justice. Law then should be transparent and accessible, and often it is not. Unduly complex procedures among other casuistries militate against just outcomes.

Law of course relates to questions of punishment and both in The Trial and, above all, in the shocking story ‘In the Penal Colony’ – surprisingly neglected by West – about a perfect execution machine, the barbarism and cruelty of legal processes are there for all to see. It is frightening to see how the condemned man submits and, in some ways, enjoys the barbarity of his torture, just as occurs to the dissident in Arthur Koestler’s 1940 novel Darkness at Noon. Today we call this Stockholm Syndrome, where you empathise with your captors.

I have always hated the death penalty and indeed torture or state sponsored cruelty, anyone who has experienced the jihadism of Roman Catholicism will know what I mean.

Fishelson’s version of The Castle at Manhattan Ensemble Theatre, January 2002.

Bureaucratic Nightmares

Kafka lived under a deeply authoritarian extended Germanic state of bureaucracy and authoritarianism then ruling the Czech Republic. A Weberian bureaucracy gone mad.

Alberto Moravia’s 1951 novel The Conformist demonstrates how a bureaucratic conformity evident in lawyers far too easily morphs into fascism. Kafka lived in a proto-totalitarian state and is often seen as someone who mystically envisages dystopian totalitarianism. In some respects, Kundera observed the completion of the projection. The full negation of the individual, and individual rights.

Now such harbingers of dystopia are right back, for want of a better expression, in fashion and the reasons for this are obvious to anyone who looks up from their screen.

We are in a new age of corporate fascism, with an ever increasingly authoritarian state. Mass monitoring and surveillance through artificial intelligence is dictating and controlling our choices. Ascendant right-wing extremism throughout much of Europe has drawn lessons from religious fundamentalism.

In this interview Professor Laurent Pech identifies the three stage process by which rogue EU states are undermining the Rule of Law and threatening democracy across Europe.https://t.co/YW85tanHgx@ProfPech @DLangwallner @broadsheet_ie @liamherrick @ICCLtweet @NMcDevitt

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) April 3, 2021

Thus, Kafka’s arguments on the dangers of unconditional surrender to authority and acceptance of its legitimacy, as well as his arguments around how consent to authority can destroy us are important points to recall. Even in our daily lives.

Both Kafka and Kundera urge us to challenge authority, and at the very least always ask: who is making a decision and why? Don’t look at the office, but at the man or women in control of it, and what he or she is purporting to do.

The enlarged Kafkaesque state – in many respects experienced by Kundera – is right back in force in the coronavirus panopticon, with the vectors of evil apparent everywhere, not least in a plethora of falsely accused and indeed framed Joseph K’s. worldwide. Let us call them the dissentient.

We have all too much faith in the law, a failing which led my friend the late Supreme Court Justice Adrian Hardiman to entitle an article on how the state falsely accused the DJ Paul Gambaccini, ‘Kafka On the Thames’; and yet faith in due process and legal fairness is one of the few values left to clutch on to.

"The cry of "emergency" is an intoxicating one, producing an exhilarating freedom from the need to consider the rights of others and productive of the desire to repeat it again and again."

Former Supreme Court Justice Adrian Hardiman (2011, in Dellway Investments v NAMA) pic.twitter.com/w77qN0IGM7— Brian Reilly (@j_reilly33) July 7, 2021

Kundera and Kafka are two titans of the Czech intelligentsia who have much to say in our contemporary era: be careful about unconditional obedience to authority and distrustful of legal processes; antennae should be raised to detect post truth nonsense and dissimulation; and witness how Communist totalitarianism has been replaced by another decline of the human condition: neoliberal degradation.

Never unconditionally comply with the edicts of authority. Just say No. Do not obey orders just because they are orders. Exercise judgment.

[i] Arne Novak, Czech Literature (translated from Czech by Peter Kussi), Ann Arbor (1976), p.170

[ii] Ibid, p.9