All our biographies, if they went back far enough, would begin by explaining how our ancestors came to be more or less enslaved, and to what degree we have become free of this inheritance.

Theodore Zeldin, An Intimate History of Humanity (London, 1995), p.7

We are facing a world in a state of perpetual conflict, which urgently requires solutions on many fronts. The sense of belonging to a place or nation has been universally and irreversibly destabilised.

Integration is a burning question, with unresolved arguments and extreme resolutions: blockages, indifference and walls.

The Refugee Crisis of 2015 was a complex phenomenon, but it was also a simple request for help: individual choices to escape miserable conditions of political and social degeneration.

I found the best response to these exhausting debates in the art of Syrian Abdalla Al Omari. His work silences the state of fear and anger flowing through news and social networks, where intelligence and compassion is failing in front of our eyes, giving way to widespread ignorance and emotive anger.

Terrified by the ‘Other’, fear reigns instead of constructive ideas and creativity. We need to re-activate the empathic part of our brains that makes us see ourselves in others, chasing a conspiracy of life instead of death.

II – Fragility

Marina Abramovic’s 1974 performance Rhythm 0 shows the fragility of the human condition. Laying on a table seventy-two objects, she invited her audience to use them in any way they chose. Once invited, they did not hesitate to select the pistol with bullets rather than feathers and roses. The performance ceased when the audience became too aggressive.

III – Empathy

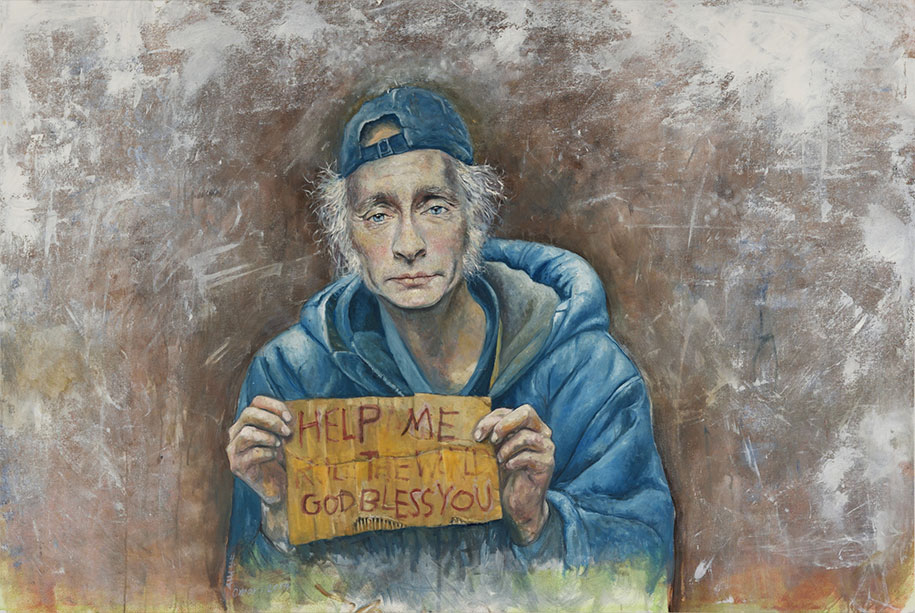

Omari’s brushstrokes confront bizarre laws and bullets, and transforms his anger into an unexpected visual awakening. He portrays political leaders as refugees. Beyond the obvious comedic value this develops empathic responses.

He says:

While depicting my subjects and developing the series, I eventually arrived at the paradoxical nature of empathy, and somehow my aim shifted from an expression of the anger I had, that I thought was the trigger, to a more vivid desire to disarm my figures and to picture them outside of their positions of power.

It is a ‘sweet revenge’ on politicians and powerful leaders, whose decisions displace innocent civilians. He continues:

I wanted to take away their power, not to serve me and my pain, but to give them back their humanity and to give the audience an insight into what the power of vulnerability can achieve.

This ‘celebration of vulnerability’ is for the artist a surrealistic experiment revealing the inner face of the problem: the inner face of both refugees, political leaders, and ourselves:

It’s time for not only artists but any other kind of profession to be more involved in what is in the social-political situation universally.

IV – Identification

According to Daniel Trilling:

In her 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism, the political theorist Hannah Arendt argued that the inability of states to guarantee rights to displaced people in Europe between the world wars helped create the conditions for dictatorship. Statelessness reduced people to the condition of outlaws: they had to break laws in order to live and they were subject to jail sentences without ever committing a crime. Being a refugee means not doing what you are told – if you did, you would probably have stayed at home to be killed. And you continue bending the rules, telling untruths, concealing yourself, even after you have left immediate danger, because that is the way you negotiate a hostile system.

Similarly Abdalli Omari writes:

When you only talk about quantity of people you totally ignore the fact that all these numbers are persons, are individual stories, are people.

What would you do in the shoes of a refugee? Would you keep moving despite the impediments?

What have we in privileged societies to fear from refugees? These are people in search of fresh opportunities, new arrivals looking to reinvent themselves. Are not many of us searching for the same thing?

*******

Portiamo Omero e Dante,

il cieco e il pellegrino

l’odore che perdeste

l’uguaglianza che avete sottomesso

We carry Homer and Dante, the blind man and the pilgrim,

the smell that you’ve lost, the equality you’ve repressed.