What do I want from you? Why do I write this text? Is it because I want to share something, or because I was told to? In considering how ‘you’ will read it, (‘you’ hopefully being someone other than ‘me,’) I would like to share some things relating to the development of viewership and audience engagement.

This is by no means a definitive list, rather, a haberdashery of sorts, my own narrative stitched through the history shelves into relevant spines, to prop up against my own bar, serving tall pints poured with personal narratives. How academic!

Good Performance

The majority of good performance dictates to its audience how they must act. Rather than being something written down in a pamphlet to digest and practice pre-show, the way you should watch the performance has been defined through the performance itself.

Live, in the moment. The only way to learn the new terms of engagement is to attend, to witness, to participate (or not participate), and most of all, to act.

It’s like ballroom dancing with a good dance partner, the leader leads, the viewer follows. Dance with a bad dancer, however, and you might be inclined to rebel, to revolt or to leave the dancefloor. I think it was Chekhov who said, show the audience a gun in the first act, you had better use it in the third.

I draw your attention to Hugo Ball, dressed up in a cardboard cylinder to perform his abstract phonetic poem ‘O Gadji Beri Bimba.’ It caused chaos among audience members as they just did not know how to react, what to take seriously, how to engage.

Language, the motherload of culture, the determiner for how we think and communicate, whittled down into a collection of sounds chirruped and chanted by an obelisk shaped man. The ramifications were huge, to challenge the central pillar of communication, attacking it in such a way, also challenged the perspectives which we garner through language, behaviours, nationalism, politics, history, etc.

How do we perform (via language) in our everyday lives after that, knowing that it has been called out for being insincere? Ball wasn’t the first artist to use this medium, before him there was Marinetti, with his ‘Zang Tumb Tumb,’ and also Russian Futurist Aleksei Kruchenykh’s

Zaum language in ‘Victory Over the Sun.’

Language strikes again:

Hans Richter. Dada, Art and Anti-Art.

Marinetti and the Futurists

Marinetti and the Futurists welcomed heckling and shouts from their audience. The viewer was crucial to the performance, so much so that they would glue them to their chairs, patches of trousers and skirts screaming off as tempers tore.

They wanted to break the compliance of passive consumption, of blind acceptance, and so agitating the viewer towards a riot was a crucial factor in their performance. This focus on the role of the viewer as a fundamental component echoes throughout the twentieth Century, most notably with Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetics. In stating that the only way to truly engage with an artwork was to be a part of it, this movement placed the viewer centre stage, the artwork’s legacy depending on their enthusiasm. Only then could the artist be sure that responsible viewing had been contracted.

Relational Aesthetics also sought to display the network of relationships necessary in creating a work of art, to blur the boundaries between negotiating the piece as creator, and negotiating the piece as viewer. But, as Claire Bishop pointed out, simply making us aware of these negotiations does not necessarily introduce a form of criticality in that it does not define what types of relationships we are looking at, if they are equal, or democratic. She criticized the vagueness of many R.A artworks, but held up Santiago Sierra as a successful Relational Aesthetics artist, for showing the subversive, and sometimes unequal transgressions that happen in many negotiations.

‘Ten People Paid to Masturbate,’ Santiago Sierra. Cuba. 2000

Roman Britain

‘The Romans in Britain’ when staged in 1980 at the National Theatre was sued by Mary Whitehouse, who accused the director Mr Bogdanov, of procuring an act of gross indecency between two males actors in the play.

The fact that no act really happened, (there was a simulation of a male rape scene) did not seem to matter, nor did the fact that Mrs. Whitehouse never actually saw the play. Her moral stance overrode these factors, and she felt obliged to tackle the theatre for staging a play which she considered unnecessary and indecent.

Fortunately, the court ruled in favour of the theatre. It was the first male rape scene to ever appear on a stage in the UK. Accounts from the opening night speak of nine hundred audience members, not shouting or walking out, but sitting frozen for the remainder of the play. ‘The atmosphere was later compared to the night in London theatres when it was announced before curtain-up that JFK had died.’

There have been recent attempts by morality campaigners to ban theatrical productions (e.g. ‘Behzti’ UK, 2004, ‘Jerry Springer, The Opera,’ 2005, and ‘Sur le concept du visage du fils de Dieu’ Paris, 2011), which brings back to the forefront the question of censorship, and deciding what narratives are appropriate for audiences today.

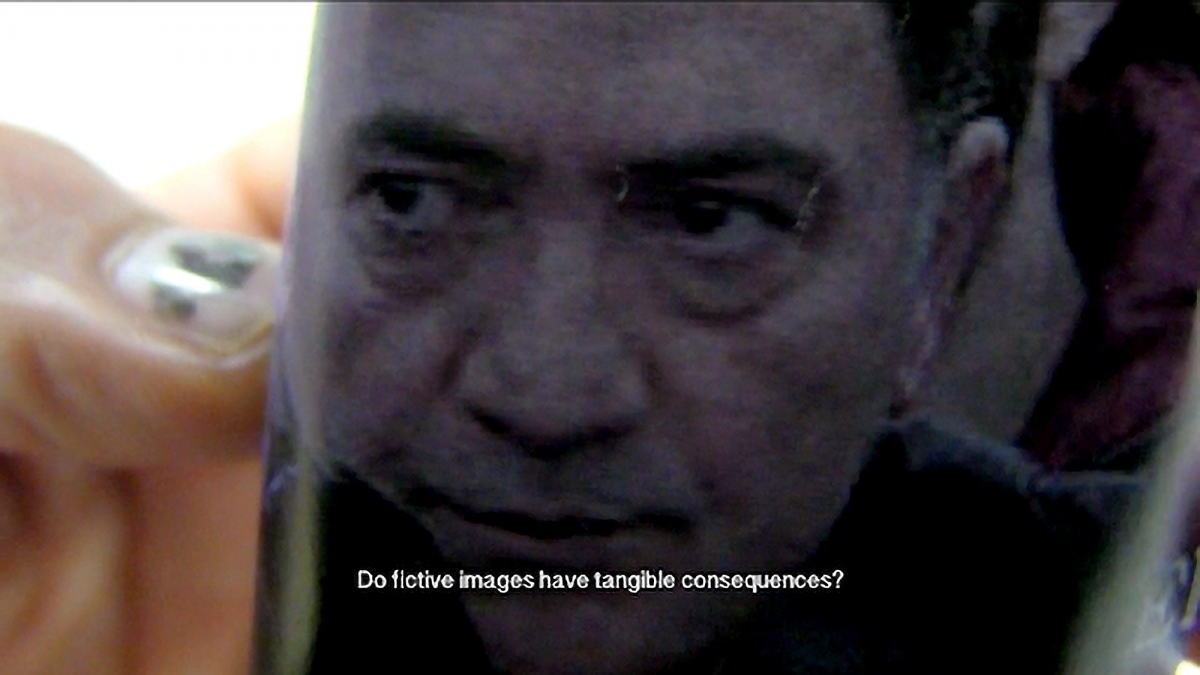

A group exhibition I was part of in Turkey 2016, ‘Post-Peace,’ was cancelled last minute by the institution, Akbank Sanat, deemed to be too culturally insensitive to stage. The offending artwork ‘Ayhan and me’ by Belit Sağ, is a video created from news archives which showed a Turkish police officer bragging about killing Kurdish people.

Belit Sağ. Ayhan and Me. 2016

In this age of fake news, and political correctness, it is more important than ever that we don’t treat audiences as children. Which begs the question; is engagement with morality absent from the modus operandi of our times?

Representing the Immoral

Art has a necessary role in presenting situations that challenge and provoke, it is through these provocations that a society sets its standards of behaviour. Rather than questioning the role of morality in art, (which doesn’t exist,) in order to be relevant, art must, to some extent, represent the immoral.

These provocations offer the possibility to stimulate reflection on and discussion around what is acceptable, and what is not, and why not. Without this avenue culture becomes something that we consume, the same way we consume McDonalds, or a Coca-cola.

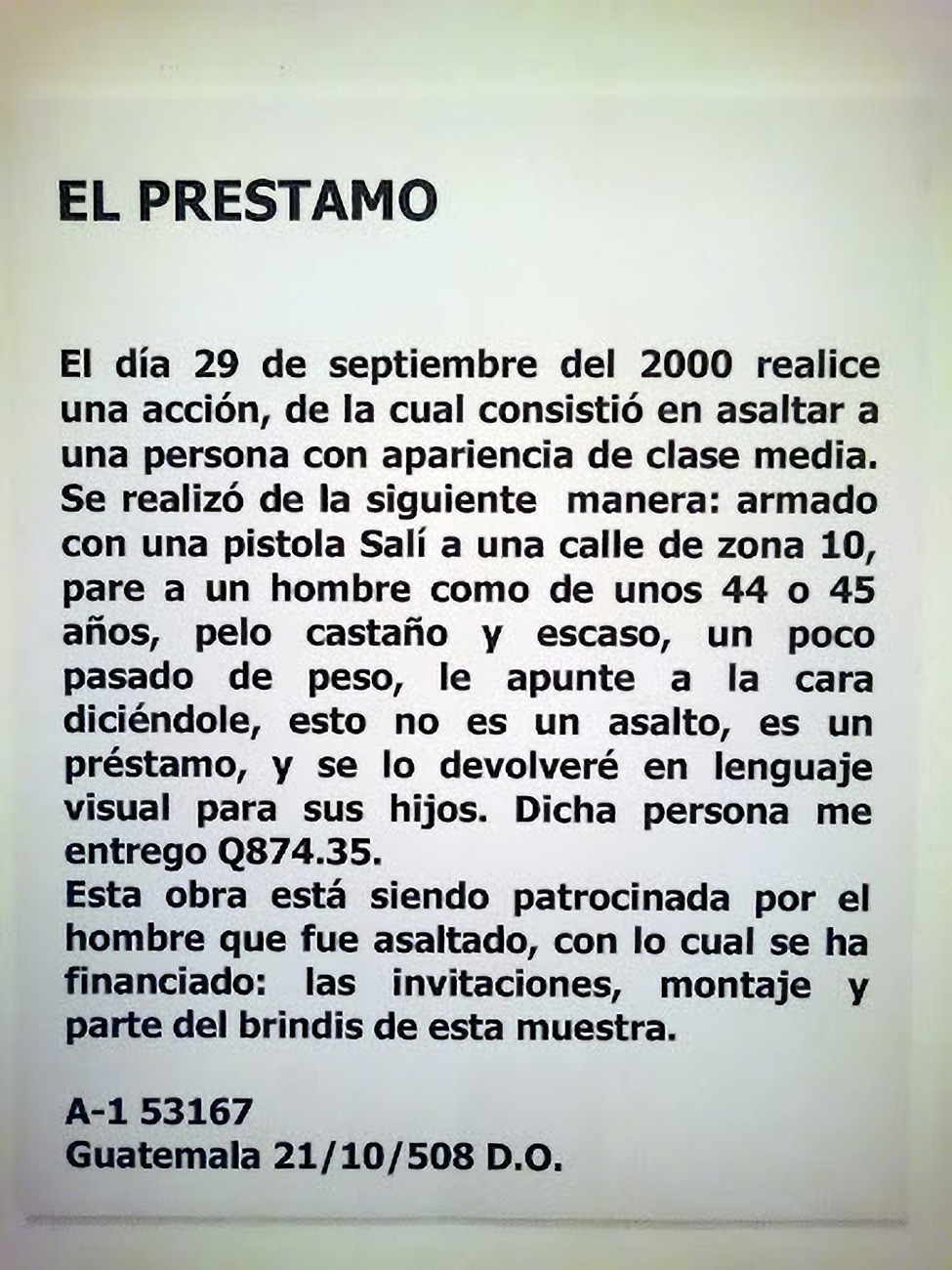

Placing the artwork in a way that the viewer can have the maximum opportunity to be aware of their role is, for me, the ideal. Here I think of Guatemalan artist Aníbal Lopez (a.k.a. A-1 53167.) For the piece ‘El Préstamo (The Loan) (2000)’ situated in Guatemala City, the artist robbed a citizen on the street at gunpoint, and used the stolen money to pay for an exhibition at Contexto. This included invitations, installation, a lavish opening reception, all paid for by this victim, now unwillingly performing as patron. Upon arrival at the exhibition, the audience learned these events through a poster on the wall, the only visual piece on display. The attending viewer became complicit in this crime by participating as viewer, and as consumer. Which makes me wonder about complicity and the act of spectating: Are not all audiences complicit?

THE LOAN. On the 29th day of September, 2000, I did an action, which consisted of assaulting a person with the appearance of middle class. It was performed in the following way: armed with a gun I went out to a street in zone 10, stopped such a man of about 44 or 45 years, brown hair and a little overweight, I pointed in his face and told him, this is not an assault, it is a loan, and will bring visual language to your children. Such a person I call Q874.35. This work is being sponsored by the man that was assaulted, who has funded: invitations, assembly and part of the toast of this sample. A-1 53167 Guatemala 21/10/508 D. O.)

Perhaps this is why the most popular form of viewing has remained the same for over a hundred years, since The Moscow Art Theatre reformed the relationship between the viewer and the stage.

Stanislavski nailed the fourth wall up and many have been banging it down ever since. The ramifications of this wave have crashed through into other art forms, television, cinema, and sometimes, contemporary art, with many collectives fighting its wake to establish other ways of viewing. This invisible wall, invented by this collective, removed the necessity of communicating directly with the audience, establishing instead an experience where the viewer is required to watch this bubbled environment, creating an altogether more realistic performance and allowing for suspension of disbelief. The audience arrive and become silent observers, flies on the wall with no responsibility.

It remains, however, the most popular way of watching something today, this disengaged mode and you may ask, should it be so?

At this moment, culture cannot serve as a salve for nervous souls, even if the (then) President elect tweeted his disapproval of Broadway actors for using the theatre to communicate their doubts about his future administration.

Art’s particular license to speak up, to misbehave, mock and imitate reality, to blur genres and disciplines, this freedom, as long as it lasts, must be deployed to prevent the normalization of the emerging authoritarian paradigm.

To recap…

Violate language and communicate it. Curse your audience and kiss their throats. Question what you’re watching. Attack ‘appropriate’ narratives by telling the truth. Replace complacence with awareness. Leverage weakness to break power. Attack acts of gross indecency by staging acts of gross indecency. Take an axe to axioms. Swallow bubbles for breakfast. Divorce disengagement.

Ask in the taking, instead of begging for scraps under the table, howl at the edges of town.

Ella de Burca. Standards. 2016

Featured Image: ‘Choke’