Content is a glimpse of something, an encounter like a flash. It’s very tiny – very tiny, content.

Willem De Kooning

The evening before we left for two days in Paris (or, more accurately, one evening, one day and one morning), solely to see the massive Mark Rothko retrospective exhibition (115 canvasses, the largest collection of his works ever shown together in one place) at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, I attended a concert given by the (nominally) Drone Metal group Sunn O))) at the National Concert Hall, Dublin.

Serendipitously, I find I can discern certain elective affinities between these two artists’ respective oeuvres – one visual and painterly, the other aural and musical – in terms of what I find most challenging and moving in art. I made the journey to Paris in an effort to answer a question I have been asking myself for a long time: why is it that I am so enthralled by Rothko’s work, above that of other twentieth century painters I admire? Correspondingly, I might invite a similar self-interrogation regarding Sunn O)))’s output: why am I so drawn to drone in different musical genres, as exponents of which Greg Anderson and Stephen O’Malley’s band are in many ways the epitome?

At first encounter, both partake of the Hegelian aesthetic in striving for the Absolute, or telos, in art: i.e. if you want to worship God, or e/in/pre-voke the Transcendental through an art work, then build something Bloody Big. Ergo, on the one hand: cathedrals as venues, banks of twelve vintage tube amplifier heads atop twenty-four speaker cabinets, enormous volume; and, on the other: chapels as locations, huge canvasses, blocks of pure, primary colour blurring into each other. However, as Rothko wrote:

I paint very large pictures. I realise that historically the function of painting large pictures is painting something very grandiose and pompous. The reason I paint them, however, is precisely because I want to be very intimate and human. To paint a small picture is to place yourself outside your experience, to look upon an experience as a stereopticon view or with a reducing glass. However you paint the larger picture and devote yourself to it wholeheartedly, you are inside it. It isn’t something you command.

In other words, paradoxically, go large for more intimacy. Rothko’s work may be characterised by rigorous attention to formal elements such as colour, shape, balance, depth, composition, and scale; yet, he refused to consider his paintings exclusively in these terms. He explained: ‘It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academicism. There is no such thing as good painting about nothing.’

Flaubert declared, with provocative hyperbole, in a letter to his great friend Louise Colet, while he was struggling with the writing of Madam Bovary: ‘What I would like to write is a book about nothing, a book dependent on nothing external, which would be held together by the inner strength of its style.’ Similarly, as John Banville has observed of Kafka:

The artist’, says Kafka, ‘is the one who has nothing to say.’ By which he means that art, true art, carries no message, has no opinion, does not attempt to coerce or persuade, but simply – simply! – bears witness. Ironically, we find this dictum particularly hard to accept in the case of his own work, which comes to us with all the numinous weight and opacity of a secret testament, the codes of which we seem required to decrypt.

There are echoes of this aspiration in E.M. Forster’s famous pronouncement in Aspects of the Novel:

Yes – oh dear yes – the novel tells a story. That is the fundamental aspect without which it could not exist. That is the highest factor common to all novels, and I wish that it was not so, that it could be something different – melody, or perception of truth, not this low atavistic form.

If Rothko’s painting can be considered ‘good’ (which it is), and is therefore, by his own lights, not ‘about nothing’, then what is it about? Scale was not an end in itself for Rothko, I surmise: it is merely a means to an end. ‘If you are only moved by colour relationships, you are missing the point. I am interested in expressing the big emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom.’

The parallels with the music of Sunn O))) need not be laboured: their work is not, or not only, about loudness for its own sake. They clearly want to make an audience feel something, be it a viscerally physical reaction felt in the chest, the abdomen, the nervous system, or something less tangible and more esoteric, something you can’t quite put your finger on. Perhaps they are seeking to show, at some profound level, that this mind/body duality problem, in terms of apprehension and appreciation, is not irreconcilable.

Both artists are exponents of a maximalism which is a port of entry for a greater minimalism. You may share a large bottle of cognac in front of a roaring fire on a chilly evening with a friend, but it is not necessary to down the lot between you in one sitting to achieve a warm inner glow. Again, maybe this apparent something/nothing, presence/absence dichotomy can be resolved by way of Beckett’s remark in his essay ‘Dante… Bruno. Vico.. Joyce’, an exegesis of Joyce’s Finnegans Wake – then known simply as Work in Progress: ‘His writing is not about something; it is that something itself.’ This chimes well with Rothko’s own proclamation: ‘A painting is not about an experience. It is an experience.’

When Rothko moved on from his early figurative work, which included landscapes, still lifes, figure studies, and portraits – even, almost unthinkably, a self-portrait – and had demonstrated an ability to blend expressionism and surrealism, he also abandoned what Philip Larkin called, with characteristic derision, ‘the myth kitty’: those Greco-Roman archetypes in which he (Rothko – and, it should be conceded, Larkin too) was well-versed. His search for new forms led to his colour field paintings, which, it is safe to say – however much we may be embarrassed by the acknowledgement – employed shimmering colour to convey a sense of spirituality.

Yet, despite almost always being classed (nominally) as an abstract expressionist, he never considered himself as one such. Startlingly, he wrote, ‘I’m not an abstractionist… I’m not interested in relationships of colour or form or anything else.’ He continued, elsewhere, to elaborate on this with: ‘I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I can communicate these basic human emotions.’

How, it might reasonably be asked, does this process take place? How is pure emotion, the sense of transcendence and the sublime which Rothko sought to transmit through abstract forms and colour, communicated without representation, figuration, narrative? Perhaps it is their very absence which clears the way for the tranquillity necessary for meditation upon the infinite. Rock music writer Jim DeRogatis titled his book on neo-psychedelic group The Flaming Lips Staring at Sound. In a form of synaesthesia, a study of Rothko might usefully bear the moniker Listening to Vision.

The paintings are not about the emotions, they are the feelings themselves. It is what it is. In this regard, one may think of another painter, whose ‘squares’ of primary colour separated by black lines are often thought of as ‘cold’: Mondrian. And yet, certain viewers confess to being intensely moved by his work.

This may all sound like a secular instance of prayer for those who do not pray – or even an ancillary form of worship for those who still do. (Certainly, both Sunn O))) and Rothko invite such a reading: the former donning their stage attire of billowing monks’ robes – floor-length habit and hooded cowl, while pumping incense-tinged dry ice at the audience and adopting hierophantic poses; the latter designing a non-denominational chapel which houses fourteen of his paintings – a possible modernist spin on the Via Dolorosa’s Stations of the Cross).

Rothko implied as much when he wrote: ‘The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.’ Within this statement, Rothko encapsulates the profound impact his art has on those who fall under its spell. His works promote an emotional response akin to a deeply personal spiritual encounter. Rothko’s intention was to engage the viewer in a dialogue that transcends words, inviting them to immerse themselves in an experience that mirrors his own unfathomable connection with his art. Through this shared emotional resonance, Rothko forges a connection with those who encounter his creations, which also offers them an opportunity to connect with something transcendent and sublime within themselves.

The artist’s son, Christopher Rothko, wrote in his introduction to The Artist’s Reality, the posthumously published book by his father from which most of the foregoing quotations are taken: ‘Like music, my father’s artwork seeks to express the inexpressible — we are far removed from the realm of words… The written word would only disrupt the experience of these paintings; it cannot enter their universe.’ Which renders my task here, and indeed Rothko père’s attempts to explain himself – if only to himself – moot. One hardly wants to be seen espousing, at this late stage of the game, high Victorian Mathew Arnold’s notion of a ‘religion of art’, or even fellow late Victorian Walter Pater’s line about how ‘All arts aspire to the condition of music’ (even if they do). Again, let Beckett – himself a notable Bible reader (to the extent that, taking a part for the whole as synecdoche does, the Holy Book might also rejoice in the alternative title The Book of Samuel) – fly to my rescue, with his definition, from Watt, of the ineffable as, ‘That which cannot be effed.’ The instrumental music of Sunn O))) might also be said to reside far beyond the written word.

Both Rothko and Sunn O))) run the risk common to any artists who deal in extremity, that of the danger of repetition blunting their vision, and of replication diminishing the sought after emotional impact of their work. This hazard is more acute in the performing arts, where audience expectation due to previous reputation is more immediately felt by the artist, and boredom at fulfilling it by doing the same thing every night with perhaps only minor variations can easily or eventually set in – although it is still to be guarded against in the plastic arts too. Indeed, Rothko was unable to enjoy much of his later success, when he considered that people might only be purchasing his work as investments, with no regard as to the ‘content’, having ‘a Rothko’ being more important to some than owning a particular Rothko because of a personal affinity with it.

His repudiation of pop and op art was partly because they seemed to him to make a virtue of repetition, and partly because their practitioners did not appear to have many qualms about viewing their work as saleable commodities, feeding a market through factory-like production processes which lead predictably to commodification, swallowed by the ravenous maw of late capitalism. (In this context, one might also fruitfully speculate on the significance of the venues for both of these shows. How did a Drone Metal group come to be playing in the National Concert Hall – an auditorium more ordinarily associated with the classical tradition? And how did Rothko’s paintings wind up in the Fondation Louis Vuitton – a patron who embodies the fads of luxury fashion [and was, inter alia, a Nazi collaborator]? Perhaps everything grows respectable, or else degrades, in the end. Or, more mundanely, becomes popular with the general public.)

While no self-respecting critic these days would want to be caught dead dwelling overlong on the separation of ‘form’ from ‘content’, it is worth referring to Susan Sontag’s musings on the conundrum in her seminal 1964 essay ‘Against Interpretation’, from which is borrowed, in an act of homage, the Willem De Kooning epigraph regarding ‘content’ as also the epigraph to this essay. In her short but wide-ranging piece, one deleterious aspect of over-interpretation Sontag stresses is how it diminishes the sensuous experience of a work of art. While her famous, aphoristic final sentence reads, ‘In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art’, the preceding, penultimate section finishes thus:

Our task is not to find the maximum amount of content in a work of art, much less to squeeze more content out of the work than is already there. Our task is to cut back content so that we can see the thing at all. The aim of all commentary on art now should be to make works of art – and, by analogy, our own experience – more, rather than less, real to us. The function of criticism should be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what it means.

‘Content’ is a term by which no writer or artist worth his or her salt would refer to what s/he makes – lest they become a finkish ‘content provider’ – and yet it is one forcefully thrust onto writing and art by the tyrannical vocabulary of commercial media, that hotbed of professionalised consumerism concerned not with the promotion of culture but with the profitable exploitation of it. This is made manifest in criticism which is thinly-veiled advertising and public relations. Again, from ‘Against Interpretation’:

Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable, conformable.

In another prescient insight, Sontag considers this notion of ‘content’ – perhaps the most contemptable term by which professional commodifiers refer to cultural material today – and how it defiles art:

Interpretation, based on the highly dubious theory that a work of art is composed of items of content, violates art. It makes art into an article for use, for arrangement into a mental scheme of categories.

In opposition to such harmful acts of interpretation, Sontag points to ‘making works of art whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be … just what it is.’

Susan Sontag

What, then, is this elusive and rarely glimpsed ‘content’ – if any – in Rothko’s work, which eludes us as we endlessly consider its forms (even if we are enlightened enough to know that they are ultimately indivisible)? And, furthermore, what does it mean? Here is a tentatively trial, and purely provisional, open conclusion.

Shortly before his death by suicide, Rothko suffered an aneurysm of the aorta. As was only to be expected, his medical advisors told him to stop drinking alcohol and smoking tobacco. (His version of being ‘off the sauce’ was the compromise of drinking only vodka, and from the bottle rather than a glass – as this was not really drinking; he remained, as he had always been, a chronic chain smoker.) He also became impotent, so couldn’t have sex. But most saliently, he was warned to stop painting large canvases, because of the physical exertion it demanded of his body. Given the shrinking of his world imposed by these new limitations on it, perhaps the question as to why he killed himself could be better recast as: why wouldn’t he?

Indeed, it is possible to argue that it was his perception – nay, his conviction – of the very thinness of the veil between this world and another one – the blurring of the borders between them reflected in the fuzzy-around-the-edges rectangular blocks merging onto larger rectangular backgrounds in his own paintings – which led him to suppose that ‘doing away with himself’ – as it is called – was merely the slewing off of one particular plain of existence for a fresh start on another. As a reader of the Talmud since boyhood, he would have been familiar with the concept (surely influenced by Hindu and Buddhist notions of reincarnation) that with the last breath, the soul breaks free from the body and endures as a form of consciousness. Beckett again, from Malone Dies: ‘…a last prayer, the true prayer at last, the one that asks for nothing.’ Even atheists, much less agnostics, can espouse a belief that spirit – if only as a materialistic concept – is somehow eternal. Unfashionable as it may be among post-structuralists and deconstructionists, something akin to a fallen, secular variety of mystical awe is undoubtedly aspired to and even realised in these engulfing, rapturous, rapture-inducing canvasses.

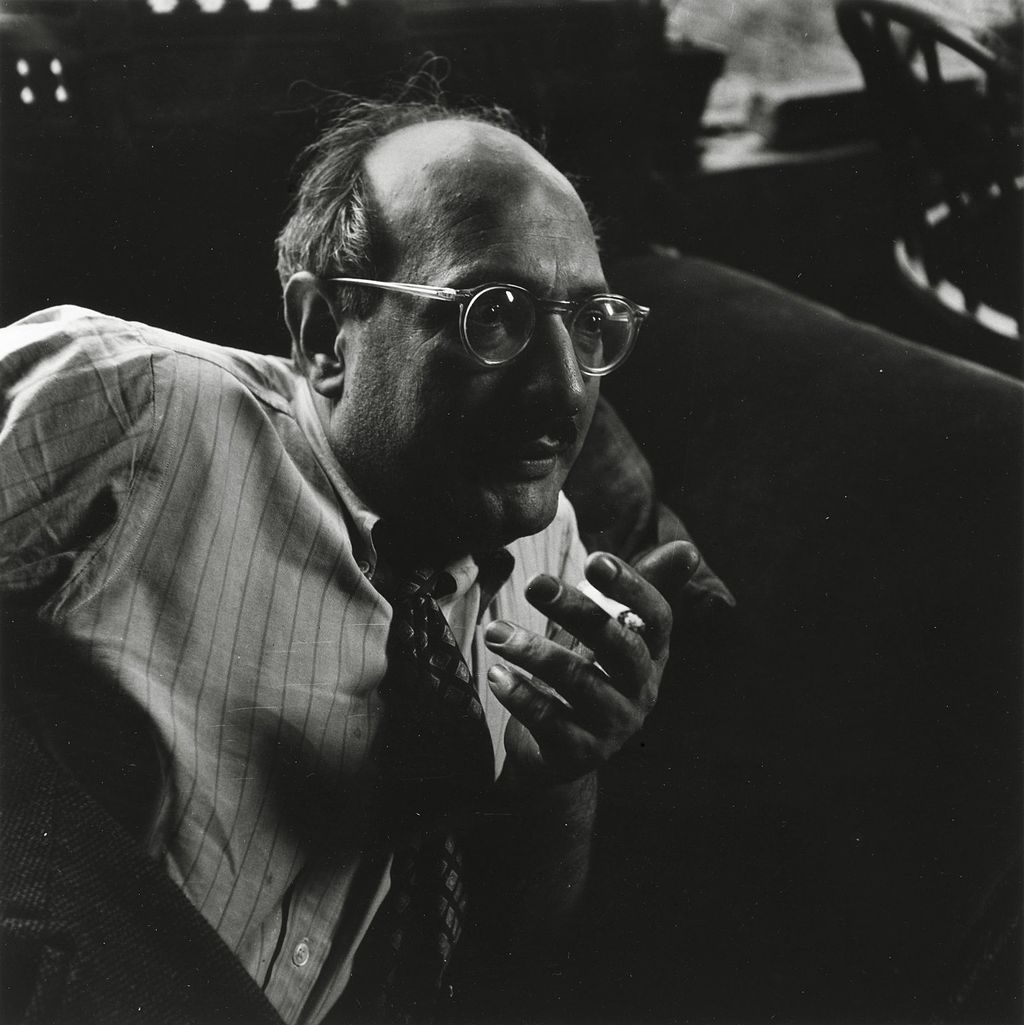

Feature Image: Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978). Mark Rothko, Yorktown Heights, ca. 1949.