THE LONG READ: In the last edition ‘How Irish Propaganda Operates’ explored how political and media duopolies uphold a dominant consensus of steady economic growth and rising rents, to the benefit of a shrinking, propertied elite. The Irish media sector is commented upon in a 2018 survey of press freedoms by Reporters Without Borders which found that the ‘highly concentrated nature of media ownership in Ireland continues to pose a major threat to press freedom, and contributed to Ireland’s two-place fall in the 2018 World Press Freedom Index.’ They also pointed to the chilling effect of high awards in defamation actions.[i] Curiously, however, that report neglected to mention the 2018 acquisition by the Irish Times of the Cork-based Landmark Media group, which includes the Irish Examiner, to create the current print duopoly.

As regards the ‘crucial constituency’ of farmers supporting the political duopoly, and concomitant failure of the government to compel reductions in GHG emissions – of which the agricultural sector produces over one third of the national total[ii] – a recent report found Ireland was the worst-performing state at tackling climate change in the EU.[iii]

This sequel explores how the Internet, especially social media, is shaping the future of Irish politics. The wider global context is a rise in support for the Far Right, a tendency to which Ireland is not immune. This resurgence is prompted by deepening inequality, and the political, moral and economic failure of the Russian Communist model, but also disorientation in the wake of technological change;and a fundamental failure at the heart of liberalism to identify universal values. We may be on the brink of a new age of barbarism, but cannot afford to give up hope of reforming state and supranational institutions.

I –Changing Politics

To my surprise a few months ago I received email correspondence from Leo Varadkar: ‘Blooming hell’, I thought to myself, ‘His Early-Riserliness, contacting me!’. ‘Perhaps he’s ready to commit to decarbonisation, public housing and basic income, and is looking to this hitherto unheralded journalist for advice. Now where did I leave my singlet…’

My ego crumpled on discovering it was political spam with a sender address of [email protected]. There would, alas, be no warm breakfast awaiting on Merrion Square after we had buddied-up at the gym.

Then I got annoyed. I had never given my email address to anyone from that organisation, let alone consented to receive Mr Varadkar’s grimacing impressions of a vlogger. I decided, however, against channelling subsequent missives straight into the ‘junk’ folder – where I would consign other unsolicited mail – to see how the story unfolded.

The emails are an intermittent reminder of just who is in charge of this country, and what he and his party pals are up to. There is little sophistication or depth to the presentations – boil-in-the-bag corporate fare – but they leach into my consciousness like the jingle on an annoying commercial, or ear worm. I may yet complain to the Data Protection Commissioner, but will settle for writing this article, for the time being at least.

With its ample resources, Fine Gael has been fastest out of the new technology blocks among Irish political parties. We may assume the rest are catching up, or will go the way of the Progressive Democrats.

The din from online chatter is rising, and parties are steeling themselves for a long digital ground war. Politics has travelled a great distance since Alexis de Tocqueville in his seminal account of Democracy in America (1830) declared that ‘nothing but a newspaper can drop the same thought into a thousand minds at the same moment.’[iv]

Now we are confronted with a barrage of information from multiple sources on a digital screen. It is early days, in historical terms, in our relationship with a new technology, but our neural pathways are already being reconfigured in ways we do not yet comprehend. Just as the invention of writing altered how the brain processes and retains information, so it has been with the Internet.

As the character Mark Renton puts it in the original Trainspotting: ‘Diane was right. The world is changing. Music is changing. Drugs are changing. Even men and women are changing. One thousand years from now, there will be no guys and no girls, just wankers. Sounds great to me.’ Politics is changing too, and the calibre of some of those in power is an indictment on the failure of more of us to get involved: as Micheal O’Siadhail warned: ‘the thieves of power / Come noiselessly in nights of apathy.’[v]

Political parties have been using focus groups, analogous to those used in the advertising industry, to test the popularity of policies for decades. Analysis of Internet browsing offers far greater and wider insights. A graphic presentation produced by Eoin Tierney for a previous article in Cassandra Voices illustrates the extent of our data leakage.[vi] Unless we take various precautions, records of our online movements are available to the highest- – or best-connected – bidder.

Some years ago I attended a conference at which one of the speakers was said to be, in hushed tones, ‘Obama’s scientific advisor’. He described how the former president’s second campaign team had made use of extensive data mining – tapping into data from Amazon purchases in particular as I recall – but warned the other side ‘would catch up in time for the next election’.

Pandora’s box had been prised open, and various troll armies have since crawled out, now led by an aging commander-in-chief with disconcertingly bright hair, while in the background another short, middle-aged man – who looks suspiciously like a trophy hunter clad in combat apparel – is whipping the troops into a frenzy. But it is important to recognise that the supposed good guys actually began this particular arms race.

Anarchic social media offers rich bounties for these excavations. In particular Facebook has an addictive quality built around the narcissistic pleasure of external validation. Its dystopian possibilities are powerfully conveyed in ‘Nosedive’ (2016), an episode of Netflix’s Dark Mirror, in which individuals rate each other from one to five stars based on social interactions. High aggregate scores are a passage to wealth and privilege, while low ratings spell poverty and exclusion. The main character ‘Lacie’ sees her attempts at social climbing implode spectacularly, ending in despair, poverty and isolation. It is as bleak a prophecy as you could find on the damage social media could wreak if we are not very careful.

Since a whistleblower revealed the sinister machinations of Cambridge Analytica on Facebook the fear that our political preferences are being conditioned by artificial intelligence tools has risen to panic in some quarters. Their trick appears to involve outspoken contributors taking ‘ownership’ of subtly positioned political messages, which confirm, amplify and ultimately modify opinions.

The commentariat links this to a quarter of Europeans now voting for Far Right parties[vii], and there is some truth to this contention. But mainstream media may be overstating Facebook’s role for their own purposes. Discrediting social media is part of ongoing attempts to salvage the sunset technology of the newspaper, which makes the case for regulation and taxation of the former. But the Internet is a multi-headed hydra, and the trolls are usually ahead of the game. Insulated and seemingly innocent WhatsApp groups are the next target, as was the case during the recent Brazilian election[viii]. We need better, transparent social media not rid of it altogether.

Twitter, unlike Facebook’s ‘secret sauce’ algorithm deciding what we see on our feeds, has kept its own feed mainly organic, although advertising is increasingly apparent, and relative anonymity seems to bring out the worst qualities in keyboard warriors. Donald Trump’s brand of hectoring nonsense seems to be ideally suited to that medium, at least to his fifty million followers. He won the presidential election with most major newspapers bitterly ranged against his Nativist agenda.

Twitter permits direct access to those who specialise in this attenuated form of speech – its one hundred and forty characters the social media equivalent of a haiku. The interactivity is key, with famous figures accessible as never before. This can even have geopolitical ramifications. At an EU summit last year British Prime Minister Theresa May offered to mediate between Europe and the U.S., to which Dalia Grybauskaitė, the president of Lithuania replied there was ‘no necessity for a bridge’, when they could all communicate with the American president via Twitter.[ix]

Irish politicians have not transitioned entirely into new media – the state broadcaster and print duopoly remain the main political battleground, or talking shop – but Twitter is an increasingly powerful vehicle for individual campaigns, and the intimacy of the Facebook environment suits it to subtle messaging.

Until we go about fixing the Internet, including social media platforms, a level of paranoia is justifiable. If Varadkar and his advisors are willing to harvest email accounts, what else are they willing to do? We know he has already floated the idea of creating anonymous accounts to make positive comments under online stories on popular news websites.[x] We have no way of knowing what conversations go on when Varadkar meets Mark Zuckerberg. Ultimately ‘we the people’ must eventually assert control over the social media we use, and integrate it into the fabric of democracy.

II – Inequality

The disorientation of technological change is only one aspect of the profound changes occurring in societies around the world. The era of the Internet coincides with, and is partly generating, unprecedented inequality – to the extent that just eight billionaires control half the human planet’s financial wealth.[xi]

As elsewhere, in Ireland we see disturbing concentrations, especially expressed in property, insulated by our political and print media duopoly from significant taxation. Thus, the wealthiest top five percent in the country own over forty percent of its wealth, with eighty-five per cent of that held in property and land. In the last financial year a mere €500 million (or just 1%) out of total tax receipts of over €50 billion, derived from land or property.[xii]

Indicatively, between 1996 and 2012 the number of qualified accountants in the state grew by a staggering eight-three percent to number 27,112. A sign of the times is that there were just 6,729 Catholic priests and nuns at that point[xiii], indicating we have moved from worship of God to Mammon.

The accountancy profession assists individuals and companies in financial consolidation. This can lapse into unethical forms of tax avoidance as was revealed in the Paradise Papers, where ‘top five’ accountancy firms channelled assets or income through countries with low taxation regimes.

High professional fees make accountants vested interests in asset preservation, and in the process many are stakeholders in the political and media duopoly. The wider influence can be seen in an obsession with imaginary money as a measure of value. In a previous article for Cassandra Voices Diarmuid Lyng identifies a ‘reducing eye – the Súil Mildeagach’ at work in contemporary Ireland which sees only uses and benefits; where ‘a cow is looked on as pounds of beef, and a tree is assessed for the length of its timber.’[xiv]

The decline of the Irish left, especially if the Labour party is counted as such, is part of a global social democratic downward spiral, seen vividly in the precipitous fall in support for the German SPD. This can partly be traced to the economic, political, and moral failure – and ultimate demise – of the Soviet Union at the end of the last century. In response, Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’ in the U.K., and Bill Clinton’s Democratic Party in the U.S. moved into the centre- or even the centre-right ground, and pursued latter-day colonialism.

The rightward drift of traditionally left-wing parties has brought an ideological vacuum now being filled by the Populist Right, which appropriate Marxist analysis, decrying capital flight and corrupt state institutions. Ironically, it is generally the New Labour old guard and Clinton Democrats that are to the fore in defending free trade arrangements, including the European Union, which is increasingly beholden to corporate lobbyists, and NAFTA. Previously free trade had been one of the major planks of conservative parties around the world, but these (including the Republican Party and the Tories in the UK), are increasingly in thrall to Far Right factions.

The ‘old’ Left is not entirely dead. The success of Jeremy Corbyn and his allies in the U.K. Labour Party in building the largest socialist party in Europe in the face of unstinting media opposition, including in the apparently left-wing Guardian, has been highly impressive.[xv] In the last election, Corbyn’s supporters bypassed mainstream media and used memes and vlogs to powerful effect online, besides grass roots activism through the Momentum organisation.

Spain’s Podemos is also bucking the trend in the face of a hostile mainstream media. It shows that social media, in concert with grass roots organisation, remains a conduit for left-wing agendas. The fear is, however, that that space is increasingly dominated by the highest bidders, who generally do not advocate that their wealth should be subject to greater taxation.

What differentiates the New Right or what used to be called the Far Right – or just plain fascists – from the Left is a marked rejection of universal values applying to all of humankind. The appeal is always to ‘our’ people, ‘our’ families, and ‘ourselves’, certainly not, ‘them’, ‘that lot’, or ‘those’ foreigners who are amassing on ‘our’ frontiers.

Fascism plays to selfish self-interest, and individual striving for status as part of an identity seen in opposition to others. Left-wing arguments are a weapon to be deployed against pampered ‘elites’, but leaders like Trump aspire to the same pampering once they have ‘drained the swamp’. Many of his supporters also aspire to climb the greasy pole that leads to a notional Trump Tower.

A comparatively generous social welfare system – in part a legacy of Labour’s period in office between 2011 and 2016 – is one reason Ireland is largely bucking the trend in terms of developing a rebranded fascism. Also, historically, our over-bearing near neighbour has been the target of nationalist ire, and we do not carry the same racist colonial baggage afflicting relations between indigenous and migrants seen elsewhere. Moreover, for all its faults, Catholicism does not distinguish between people on the basis of ethnicity or race. But the universalism of the Old Left and Catholicism are fading away and, as in the 1930s, Ireland is not immune from continental movements, especially as the Housing Crisis and evictions ensue.

Ascendant neo-liberalism does not encourage xenophobia. It is bad for business. Migration keeps down labour costs, and ethnic variety generates economic dynamism. The late Peter Sutherland, neo-liberal high priest, was one prominent supporter of tolerance.[xvi] But free movement of people is only an addendum – almost a good will gesture – to the core principal of neo-liberalism: the free movement of capital and individual enrichment. Contemporary fascism pitilessly highlights any policy failings relating to integration policies, while only superficially addressing capital flight, as unscrupulous politicians like Trump (and others) are often self-interested players themselves.

III – Wasted Lives

The late Zygmunt Bauman argued that economic migrants become scapegoats as long as the real powerbrokers of a neo-liberal Globalisation are untouchable. In his book Wasted Lives (2010) he contends:

Refugees and immigrants coming from ‘far away’ yet making a bid to settle in the neighbourhood, are uniquely suitable for the role of the effigy to be burnt as the spectre of ‘global forces’, feared and resented for doing their job without consulting those whom its outcome is bound to affect. After all, asylum-seekers and ‘economic migrants’ are collective replicas (an alter ego? fellow traveller? mirror images? caricatures?) of the new power elite of the globalised world, widely (and with reason) suspected to be the true villain of the piece.

Like that elite, he considers:

they are untied to any place, shifty, unpredictable. Like that elite, they epitomise the unfathomable ‘space of flows’ where the roots of the present-day precariousness of the human condition are sunk. Seeking in vain for other, more adequate outlets, fears and anxieties rub off on targets close to hand and re-emerge as popular resentment and fear of the ‘aliens nearby’. Uncertainty cannot be defused or dispersed in a direct confrontation with the other embodiment of extraterritoriality: the global elite drifting beyond the reach of human control. That elite is much too powerful to be confronted and challenged point-blank, even if its exact location was known (which it is not). Refugees on the other hand, are a clearly visible, and sitting, target for the surplus anguish.[xvii]

This kind of scapegoating is beginning to be seen in Ireland. A small online publication www.theliberal.ie offers a news carousel, previously plagiarized[xviii], alongside vindictive comments about migrants. One headline from November 12th read: ‘Uproar from locals as Wicklow hotel set to become direct provision centre’, the ‘report’ by James Brennan went on to say:

‘Locals are said to be “very concerned” over the proposed centre with one social media telling The Liberal: “Locals have held meetings about it and have both privately and publicly stated that they’re very concerned about the new centre. There will be uproar if this goes through”.

More disgraceful even than this ‘post-truth’ abandonment of evidential standards, is a headline to another ‘report’ written by James Brennan, which read: ‘As more migrant Direct Provision centres pop up, a 48-yr-old homeless Irish man DIES on the street in Waterford’. The message is clear: it is a zero sum game between homeless Irish dying on the streets, and migrants who are being provided for. The publication was also vocal in its support of Peter Casey’s Presidential candidacy. He made incendiary comments about members of the minority Traveller community – a traditional Irish scapegoat.

Interestingly, the editor and owner of the magazine, Leo Sherlock, is the brother of Cora Sherlock, deputy chairperson of the Pro-Life Campaign. Well accustomed to the emotive language of protecting ‘our own’, it could be that the Pro-Life campaign will provide the resources and know-how for a new campaign against immigrants, just as in America the Far Right has moved from anti-abortion to anti-migrant.

In a disturbing turn of events, investigative journalist Gemma O’Doherty has adopted anti-migrant slogans from the Far Right playbook, especially attacking George Soros.[xix] She recently tweeted that his ‘twisted Open Society Foundation … seeks to destroy nation states’.[xx] Also, her Youtube channel recently featured an interview with John Waters in which both interviewer and interviewee conveyed the idea of a migrant tide overwhelming Ireland[xxi], a country more sparsely populated today than in the mid-nineteenth century.

As wealth inequality rises, and homelessness increases, in this small open economy a desperation sets in that is easily manipulated. The Celtic Tiger has become a Paper Tiger, where most of the population does not enjoy the fruits of extravagant economic growth. For most rising gross domestic product leads to rent hikes and unaffordable property. As Bauman explains, in circumstances where the global elite are untouchable, outrage against vulnerable outsiders is likely to follow.

IV – The Mediated People

Technology is leaving a profound impression on all our minds. The smart phone is altering homo sapiens at a profound level of consciousness. We are now, as Bill McKibben puts it, a ‘mediated species’:

Everyone I know seems a little ashamed of the compulsive phone-checking, but it is, circa 2017, our species-specific calling card, as surely as the bobbing head-thrust identifies the pigeon. No one much likes spending half the workday on e-mail, but that’s what work is for many of us. Our accelerating disappearance into the digital ether now defines us—we are the mediated people, whose contact with one another and the world around us is now mostly veiled by a screen. We threaten to rebel, just as we threaten to move to Canada after an election. But we don’t; the current is too fierce to swim to shore.[xxii]

The compulsive checking is attritional and ultimately lonesome, as we avoid direct contact with one another. George Steiner attributes these habits to a ‘dread of solitude, an incapacity to experience it productively’[xxiii], which afflicts the young, but this extends well into old age.

Linked to the advance of the smart phone is a declining opportunity for book reading. The Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye identifies the properties of the book with the preservation of democracy itself. It is he says the:

by-product of the art of writing, and the technological instrument that makes democracy a working possibility – avoiding all rhetorical tricks designed to induce hypnosis in an audience, relying on nothing but the inner force and continuity of the argument … Behind the book is the larger social context of a body of written documents to which there is public access, the guarantee of the fairness of that internal debate on which democracy rests.

The book is non-linear, he says, allowing us to flick back and forth: ‘we follow a line while we are reading but the book itself is a stationary visual focus of a community.’

He distinguishes this from:

the electronic media that increases the amount of linear experience, of things seen and heard that are quickly forgotten. One sees the effects on students: a superficial alertness combined with increased difficulty preserving the intellectual continuity that is the chief characteristic of education.[xxiv]

Frye was writing in the 1970s when electronic media meant television. He might despair at contemporary attention spans, with kids unhinged and transfixed by a Snapchat that brings the inbuilt obsolescence of a social media posting to the next level. But he might also encounter knowledge and insights far exceeding those he found in his own less technology-addled students.

We have developed remarkable specialisms through advances in book-learning, but these are increasingly remote from one another. The Internet brings more generalised understandings – new horizons of knowledge – which could de-mystify formerly esoteric fields and inaugurate Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (d.1832) vision of weltliteratur, ‘world literature’, and perhaps more clearly, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s (d. 1716) dream of a bibliotheca universalis, a ‘universal library’, where expert insight could be available to all, everywhere. It could really lead us into thinking more globally. But this beast needs considerable taming.

The raging digital torrent is inherently unstable, as the content on any screen (including this article) can easily be tampered with. This makes it easy to develop superficial arguments that shift with circumstances. But latter-day fascists are arguably less ominous a presence in the absence of complex ideological statements, conventionally expressed in books, such as Karl Marx’s Das Kapital, or even Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. As the dissident Soviet writer Aleksander Solzhenitsyn put it: ‘Shakespeare’s villains stopped short at ten or so cadavers. Because they had no ideology.’[xxv] Thus, even the book, which performs an important role in preserving democracy, can, paradoxically, be used to undermine it. Similarly, the Internet can have positive and negative effects on our politics.

The online contributor may exert an influence on the outcome of elections and referenda but there is a sedentarism to his political participation. How many people attended Donald Trump’s inauguration? Historically, any political credo lacking a clearly outlined ideology tends to lack durability. What will remain of Trumpism after Trump? This recalls Percy Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias’: ‘Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare / The lone and level sands stretch far away.’

Similarly, the incipient Irish Far Right lacks a convincing ideologue. John Waters has an intellect to be reckoned with, but it is difficult to see how he can reconcile the universal values of the Catholic faith he espouses with the xenophobia evident in Far Right movements. Moreover, Ireland is an increasingly liberal society – even decriminalisation of marijuana cannot be far off – where Catholicism is commonly disparaged, but the policies of the duopoly which brought the rise in rents, and a Housing Crisis, threatens a new form of serfdom, or rage on the streets.

V – A New Age of Barbarism

Apart from technological shifts, and the moral and political vacuum brought by the demise of the Soviet Union, which permitted a corporate takeover of societies, the value system of a dominant neo-liberalism rests on decidedly shaky foundations. The philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre identified a ruling ‘Emotivism’: ‘the doctrine that all evaluative judgments and more specifically all moral judgments are nothing but expressions of preference, expressions of attitude or feeling, insofar as they are moral or evaluative in character.’[xxvi]

In other words we operate at a time when justice, including economic justice, is seen as an expression of arbitrary norms. MacIntyre traces this to the Enlightenment, when David Hume and later Fredrich Nietzsche led the attack on the universal values which the Aristotelian philosophical tradition had laid down. Thus, Aristotle’s The Nicomachean Ethics begins: ‘Every art and every scientific inquiry and similarly every action and purpose, may be said to aim for some good.’[xxvii] In contrast liberalism, or Emotivism, identifies no “good”, only self-interest.

In what is a remarkable passage MacIntyre despairs at the onset of a new age of barbarism:

It is always dangerous to draw too precise parallels between one historical period and another; and among the most misleading of such parallels are those which have been drawn between our own age in Europe and North America and the epoch in which the Roman empire declined into the Dark Ages. Nonetheless certain parallels there are. A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead – often not recognizing fully what they were doing – was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness. If my account of our moral condition is correct, we ought also to conclude that for some time now we too have reached that turning point. What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our present predicament. We are waiting not for Godot, but for another – doubtless very different – St. Benedict.[xxviii]

So what are Irish “men and women of good will” to do in these times? Retreat from the Dublin metropolis and carve out cooperative self-sufficient communities? This is one alternative. But the European imperium has not been lost entirely, and the pressing environmental problems of our time require world governance. Moreover, multilateralism is the only way to preserve peace in the nuclear age.

The institutions of the Irish state and European Union at present do not serve the interests of the people, but this could change if a broad Left-Green alliance, espousing universal values, is forged. In this respect, Irish progressives should get behind a new group, led by the economist Thomas Piketty, offering prescriptions for a fairer and more sustainable Europe.[xxix]

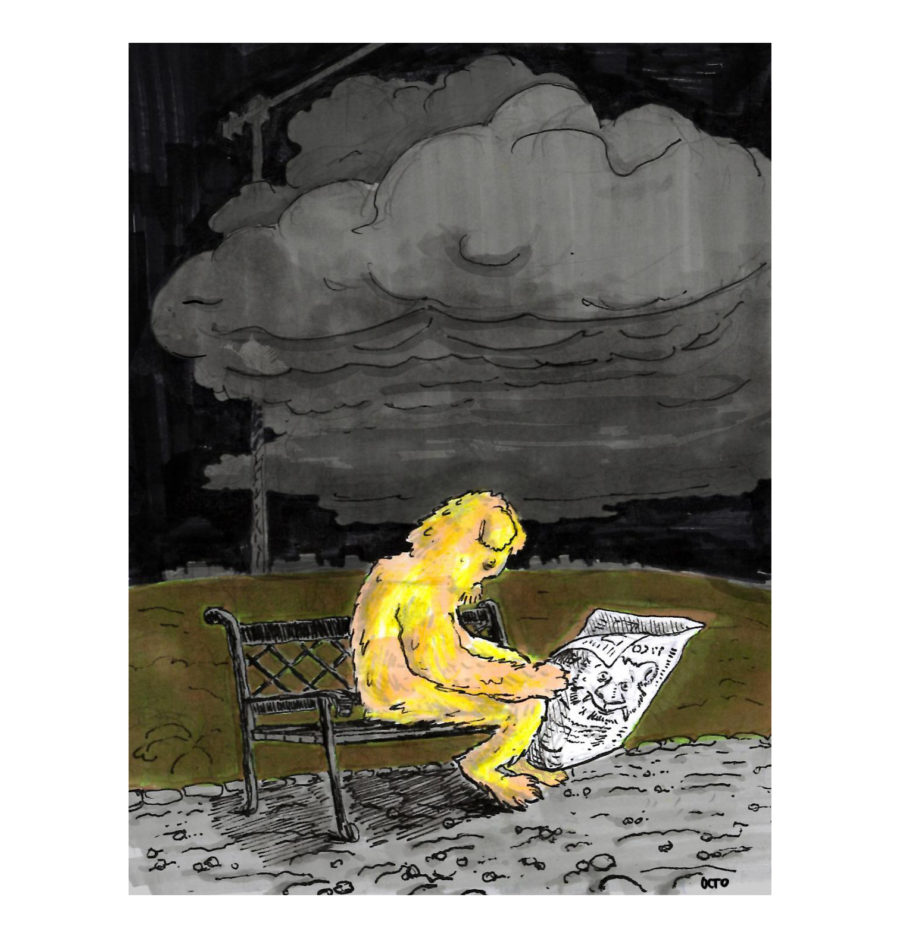

Irish Democracy is in for a long bumpy ride as we struggle to contain our online urges and the challenge of grotesque inequalities. To counteract a slide into barbarism, we must think globally and act locally, doing what we can in our own way, and never succumbing to despair. In these times we also need artists to sustain us.

Did you know that Cassandra Voices has just published a print annual containing our best articles, stories, poems and photography from 2018? It’s a big book! To find out where you can purchase it, or order it, email [email protected]

[i] Reporters Without Borders, ‘Ireland: Unhealthy Concenrtation’, World Press Freedom Index 2018, https://rsf.org/en/ireland, accessed 12/12/18.

[ii] Ciaran Moran, ‘Emissions from agriculture increase by almost 3pc in 2017 due to dairy expansion’, Irish Independent, December 8th, 2018.

[iii] Jeo Leogue, ‘Ireland worst performing European country at tackling climate change’ Irish Examiner, December 10th, 2018.

[iv] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, translated by Henry Reeve, Hertfordshire, Wordworth Editors Ltd, 1998, p.220.

[v] Micheal O’Siadhail, The Five Quintets, Waco, Baylor University Press, 2018, p.149

[vi] Eoin Tierney, ‘A Guide to Preventing Data Leakage’, Cassandra Voices, June 1st, 2018.

[vii] Paul Lewis, Seán Clarke, Caelainn Barr, Josh Holder and Niko Kommenda, ‘Revealed: one in four Europeans vote populist’, The Guardian, 20th of November, 2018.

[viii] Tom Phillips, ‘Bolsonaro business backers accused of illegal Whatsapp fake news campaign’, The Guardian, 18th of October, 2018.

[ix] Andrew Rawnsley, ‘Mrs May discovers you can’t be a bridge builder and a bridge burner’, The Guardian, 5th of February, 2017.

[x] Diarmaid Ferriter, ‘‘Leo Varadkar: A Very Modern Taoiseach’ is shallow, flimsy and exaggerated’, Irish Times, September 8th, 2018.

[xi] Melanie Curtin, ‘These 8 Men Control Half the Wealth on Earth’, Inc., undated.

[xii] David McWilliams, ‘Why do we tax income instead of wealth?’, October 9th, 2018, http://www.davidmcwilliams.ie/why-do-we-tax-income-instead-of-wealth/, accessed 10/12/18.

[xiii] Tony Farmar, The History of Irish Book Publishing, Stroud, The History Press, 2018, p.12

[xiv] Diarmuid Lyng, ‘A Hurler’s Silver Branch Perception’, Cassandra Voices, June 1st, 2018.

[xv] Dr Bart Cammaerts, ‘Representations of Jeremy Corbyn in the British Media’, ‘The London School of Economics and Political Science’, http://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/research/research-projects/representations-of-jeremy-corbyn, accessed 9/12/18.

[xvi] Ruadhán Mac Cormaic ‘Selfishness on refugees has brought EU ‘to its knees’, Irish Times, December 26th, 2015.

[xvii] Zygmunt Baumann, Wasted Lives, Modernity and its Outcasts, Oxford, Polity Press, 2004.

[xviii] Joe Leogue, ‘TheLiberal.ie goes offline amid plagiarism row’, Irish Examiner, January 10th, 2017.

[xix] Jon Henley, ‘Enemy of nationalists: George Soros and his liberal campaigns’, The Guardian, 29th of May, 2018.

[xx] Gemma O’Doherty, ‘George Soros names 5 Irish MEPs @MarianHarkin @LNBDublin @MaireadMcGMEP @SeanKellyMEP @brianhayesMEP as proven or potential allies of his twisted Open Society Foundation which seeks to destroy nation states. Which of them will deny this?’, December 1st, 2018, 12:32pm. https://twitter.com/gemmaod1/status/1068965965940043777, accessed 11/12/18.

[xxi] Gemma O’Doherty, ‘John Waters on the death of Ireland and the ideological cesspit that is the Irish media’, Youtube, November 30th, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yEnOwn4v2Yk&t=36s, accessed 10/12/18.

[xxii] Bill McKibben, ‘Pause We Can Go Back!’, New York Review of Books, February 9th, 2017.

[xxiii] George Steiner, Grammars of Creation, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2001, p.262

[xxiv] Northrop Frye, Spiritus Mundi – Essays in Literature, Myth and Society, Indiana, Indiana University Press, 1976, p.8

[xxv] Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, New York, Perennial Classics, 1974, p. 173.

[xxvi] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, Second Edition, London, Duckwork, 1985, p.8-9.

[xxvii] Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics, translated by J. E. C. Welldon, London, Prometheus Books, 1987, p.9.

[xxviii] Ibid, p.263

[xxix] Jennifer Rankin, ‘Group led by Thomas Piketty presents plan for ‘a fairer Europe’’ The Guardian, 9th of December, 2018.