Part I

“DON’T QUIT” My father’s mantra was taped to the dull beige wall above his bed. Its edges were a little worn after being ripped down from one hospital wall and taped to another, for years. Deafening was the respiratory wheezing which somehow managed to be erratic and yet, constant at the same time. As a family, we were drowning in an aching cesspool of disease, but it defined that life was still present. It defined that my father was still alive. So we sat. We waited. Held on to each breath. Hour after hour. Night after night. For the better part of those last three months. The reality was, if not in the physical sense, in an emotional one, I’d been there for seven years.

That hospital was an all-too-familiar environment. Homey to us all. The room scattered with bits of our life. A keyboard, magazines, photos, Dad’s guitar, a soapstone carving of a seal he was crafting. It was all there, in an attempt to provide us any peace. The doctors and nurses, porters and administration, housekeeping and parking attendants, other patients and their visiting families. Everyone within that sphere were part of what was to us, “home.”

Better than sleeping upright in the chair, or awake and listening to my Dad struggle for breath, was the penthouse stairwell landing. It morphed into a makeshift sleeping area we siblings fought for, and as the youngest, most often I lost.

It had been seven years since we got the news. My mother and father were in the hospital room. While out in the dim hall, I waited. Glancing around at the sterile surroundings, I was excited to see my father again, but nervous. Why were we in this strange place? He’d been tired and required some tests. Whatever that meant.

“Your father has cancer.” Those were the words.

“Can I catch it?” I asked.

“No.”

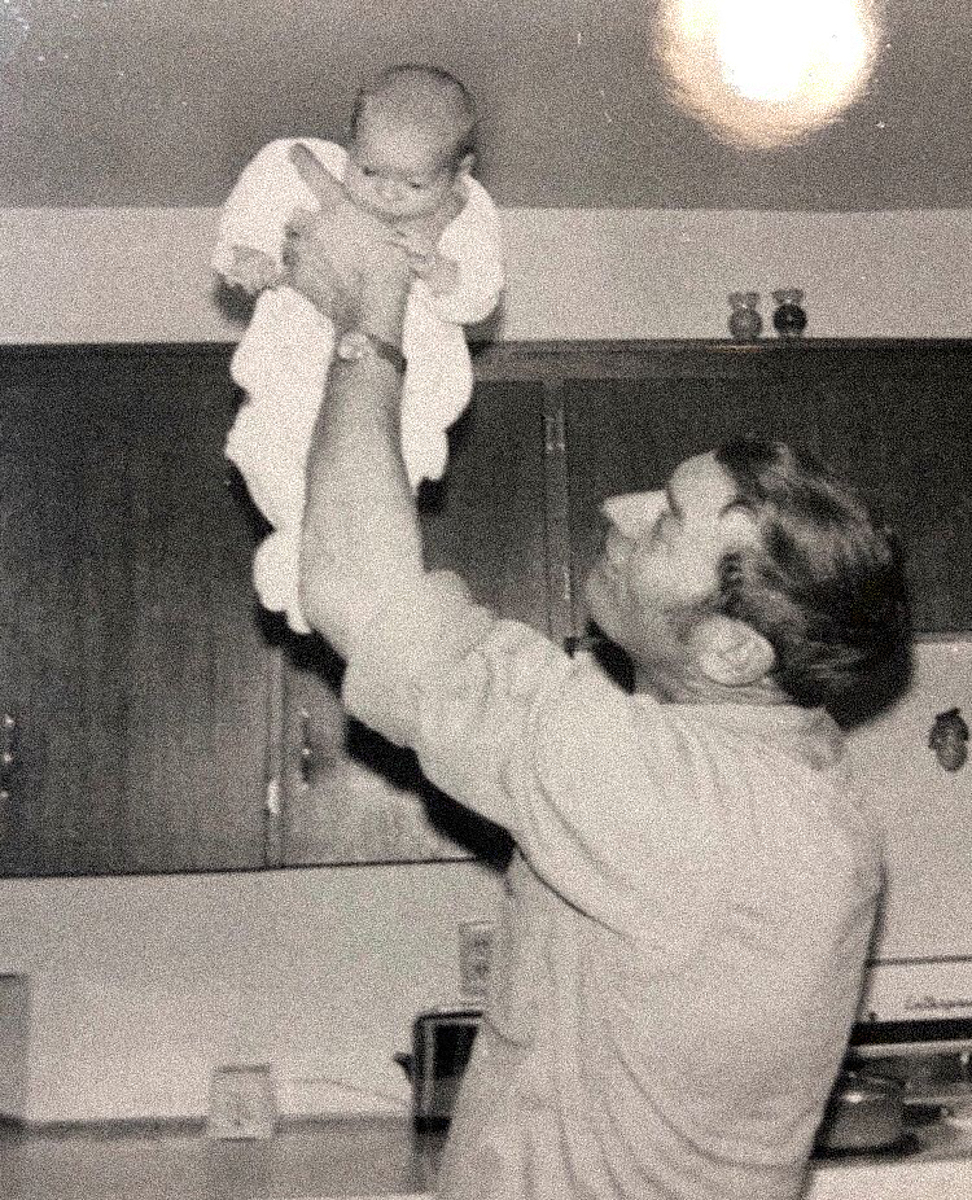

I wondered what cancer was. It made Mom’s eyes puffy. She’d been crying. She was sad. At Daddy’s side, I held his hand, like I always had. Squeezing my little fingers, he looked into my eyes and smiled. My mother held his other hand, small gasps escaping her lips, and tears in her eyes.

“Your Dad will have some treatments to make the cancer go away,” they said. “He will be losing his hair.”

HALT! I was horrified. What did they mean “lose his hair?” Why? Where was his hair going? Dad would be bald?

“It could come back in any color.”

“Like pink, or purple or red or blue?” I quizzed.

“Sure!”

Dad’s hair didn’t matter, but I knew by the look in their eyes, and their strained voices, that something was wrong. All attempts to convince me made it more obvious that life would never again be the same. At age six I was unable to comprehend the scope of sadness that would become our reality. From this moment forward, the course of my life would be altered. Forever.

He was given thirty days to live. My mother was just thirty-six and would be left to raise a family of five alone. Then, during the subsequent seven years, in cycles of thirty to ninety days, he was given additional time to live. It would prove to be an unimaginable journey: fear, insecurity, loneliness, lack of identity, hardening, pain. The canvas appearing bright, a guise brimming with fun, friends and popularity, Yet, the brush strokes, and the mediums were layered; opaque textures veiling a stark and sombre reality.

Dreading the last buzzer of the day at school became a mainstay. What would I come home to? I turned age seven, eight, and nine. The years went on, and some questions remained the same, some changed. Would I end up all alone? Would that old lady with the weeping mole be my nanny once again, or would I be shipped off to whomever would take me? I wondered this knowing I might be with them for more than a month. Ages ten, eleven, and twelve passed, and the pain continued. Would my parents be home, or would the chemo-induced nightmare have Dad slumped over the porcelain, convulsing, heaving, and regurgitating nothing again? Would he remember me today? Would he get lost driving, if he could even drive? Would Mom be crying? Of course, she always cried. And would the ambulance be backed up to the door with Dad crawling to the stretcher, as a form of pride? At age 13, I wondered would Mom survive? Would I?

He was dead. My father. Lifeless. Hollow. Dead. Dad died from a harrowing seven-year battle with cancer. A battle I would ultimately recognize as being a significant moment in my own life. It would serve as a catalyst for the person I became. Silent. Sober. Glazed, I sunk into a therapist’s worn velvet sofa, deep in that tearstained domicile of heart wrenching human agony. Behind a calm façade, the only evidence of anguish I saved for that lacerated outlet of my pain, were the petals of a crimson poinsettia. Sympathetic yet, clinical, I felt my therapist’s analytical eyes summing me up. I didn’t want to be here. I wanted a reprieve. Wanted to melt into the blueness of his sofa. Blend into his flat, silent walls. Walls which had absorbed the malaise of multitudes.

That excruciating sound had ceased. The agonizing gasps for life that accompanied each passing second for the past month stopped. That last breath of life had taken him with it, leaving a silent, still, deserted form laying there. My Dad was dead. I didn’t know it then, but I was now part of a club. A club that I’d find out, in later years, was unlike any other. Neither prestigious, nor chic, it was nevertheless a club. It was a club that would give bearing, and direction to the future me. The club would open doors. And these doors would lead me into the lives of others.

Part II

Club Life. Who are we but an assemblage of clones. Xeroxed human forms convinced that by seeking individuality, we don’t exploit its very existence. As club members, we attend the club of the moment, striving to be a part of the in-group; a clique, attempting to carbon copy the look, speech, smell, and thoughts of others. Lost in a sea of conformity, we’ll adapt to anything familiar for that feeling of wholeness. Righteousness. Acceptance. Gregarious sheep, we follow our instinct to flock, and when separated from the group, we become agitated and crave safety from lurking predators who may challenge us, or our character. We search for the lead sheep to follow down the road. The road to conformity right over an imminent cliff at the peril of what makes us unique. Original.

We could choose to believe that we are beautiful. Singular individuals. Designed to be a happy result. An impeccable concoction of experiences that when blended together become our life as we know it. Like a recipe, we are just ingredients, temperatures, measurements, outer elements, and mediums, and who is cooking. All these play a role for the outcome of the dish that is this life. Our ingredients and our process contain variables both habitual and fortuitous. Making each and every decision, experience and moment, directly affect the core of who we become. Internally. Externally. These uncertainties and variables add the fundamental flavour and the texture to our souls. Our lives mould us into who we will be.

So, let’s talk food, spices to be specific. For the most part, spices are added in small, portions. Sometimes so insignificant they are invisible to the eye. When blended, they often vanish. Yet their potency and flavour are a game changer. How much spice, tasty or disgusting has been added to the lives of others and while unaware of why, still we somehow sense something in their presence.

Some ingredients seem similar. But there exists a vast difference between, vinegars for instance. Selecting white, cider, malt or balsamic, would we then pour the potent fluid directly from its bottle, or over a fire, find its thick sickly sweet reduction? Faced with different conditions, the same ingredient reveals otherwise hidden characteristics from the inside, out.

Measurements; a pinch, an ounce, a cup; the abundance of an ingredient or lack thereof can build or destroy what we perceive as the expected end result. Do we have enough? Is it too much?

And who is cooking in your kitchen? Is that a Three Star Michelin Chef preparing avocado mousse with green pistachio oil, garnished with fleur de sel? Or is it Grandma’s loving hands putting her warm heart fondly in to preparing her mother’s, age-old family recipe of roast beef and mashed potatoes? Then there’s the fifteen year old kid slinging burgers at the local drive-thru, just to make a buck.

How’s the heat? Low and slow? Is the lid on or off? Are we baking or grilling over mesquite on the barbeque? Have you tried deep fried? Is stuff sautéed on the stovetop or simply served, cold and raw? An utter absence of heat changes everything. Regardless of method employed, each element plays an intrinsic role in what will be plated and served to please or repulse one’s appetite. And at the end of the day all we can say is that dinner is served, or Bon Appetit!

As humans full of a variety of ingredients; mediums, measurements, methods and so forth, we differ and yet find what we share in common. Lonely in our fight to be profoundly unique, conversely, we crave to fit in and be part of a group. We want a club that will unify us. Bring us together in a harmonious and understanding manner, and thus the recipe.

The universal understanding of clubs comes decked out in the all-knowing perceived costume of book clubs, tennis clubs, rotary clubs, dance clubs, bike clubs, yacht clubs, even golf clubs. But the clubs in disguise that resonate in all of our lives each and every day are blatantly obvious yet not drafted or defined. These are the clubs of reality, the clubs of experience, the clubs of heartache, sorrow, joy, bliss, danger, and courage, LIFE.

These clubs build the foundation within us to erect relationships with others based on empathy and understanding of shared mutual knowledge and experiences. These clubs categorically hoist us into levels of sameness. Ultimately allowing us to relate with one another in a way that can be truly understood. The clubs become a vast and endless springboard to deeper relations. Club menus adorned in new attire are decorated and large; lost a parent club, pregnant club, married club, divorced club, singles club, couldn’t have a child club, owned a business club, the LGTBQ club, been an addict club, had a daughter club, had a son club, had a sister club, was abused club, lost a job club, went bankrupt club, made a million club, survived cancer club, chronic pain club, attended university club, wrote a dissertation club. I think you get the picture.

Part III

It was overcast when I left my scheduled ultrasound, childless, except for the unborn one inside me. I was enjoying every moment of being seven months pregnant with my second. A clingy camouflage dress did anything but that for the basketball-esque lump that bulged beneath it. I ran my hands down and around us both, saying, “I love you.” I even pressed on its body parts. Hoping to awaken our little one. Feel those movements that made me feel so whole. So beautiful. So utterly complete. Growing at the proper pace, meant together we were squished behind the steering wheel, in order for my feet to touch the pedals. But these nuances are nothing. These petty discomforts, which arise with pregnancy, pale in comparison to being a conduit of life.

Had I seen a penis? Was it a boy or girl? Would it go to an Ivy League school? Questions about my unborn child played out in my head as I drove down the street that afternoon. Wait, would my little girl adjust or object to her new room? Her new sibling? And what about the nursery? What about the crib? The decorating around it was nowhere near complete. There would be plenty of time for that, although I anticipated an early arrival. This would be a carbon copy of my previous little miracle who entered the world two weeks early. I had so many questions and thoughts. So much newness, I was about to burst.

In a couple of months, we’d have two children. Two years apart. Perfect! Oh and I wouldn’t split my love. There was enough of me to go around! I would DOUBLE my love. Yes. It would all be perfect. U2’s song, “It’s a Beautiful Day” played on the radio. I sang along. Well, the words I knew. “It’s a Beautiful Day, don’t let it get away, it’s a Beautiful Day, don’t let it get away.” “You’re on the road but you’ve got no destination you’re in the mud mmm mmm mmm . . . you’ve been all over and it’s been all over you.”

I hummed and mumbled through the rest. It was perhaps a grey day, but it was still beautiful to me. Seemed I always left those ultrasounds in such a euphoric state, after observing the little life inside me. A life I had played a major part in creating. And for those nine precious months, I took seriously and welcomed all responsibility for controlling the wellbeing of this little miracle inside me.

The phone in my lap vibrated before it rang. Competing with Bono’s, “What you don’t have, you don’t need it now,” my husband answered my singsong hello.

“Honey, great news! Your doctor just called and has the results from your ultrasound.”

Thump, thump, thump. Heart pounding. Pounding. I veered off the road. I wanted to back up, Wake up. Start the day anew. You don’t get results from ultrasounds unless they are bad. And no, not personal calls from your doctor, only minutes afterward. I couldn’t hear anything. The world spiralled around me. I needed air. At that moment, I knew. All those hopes and dreams I’d entertained in my head moments before, of my unborn child, would NEVER be. I knew.

The five days to follow were some of the most agonizing, I’d ever experienced. Ultrasounds. Amniocentesis. Internal exams. External prodding. Counselling. Tears. Decisions. Conclusions. Devastation.

Four days later, I huddled with my husband in the boardroom of a hospital in another city. White walls surrounded the big brown table where we sat on insignificant office chairs forged from metal and woven fabric. Other than that, the room felt empty. Lifeless. Not counting the dozen or so medical professionals gathered to go over the prognosis, answer any questions and hear our decision. Considering that my husband chose to leave it in my hands, head and heart, our decision was actually mine.

Introductions were made after everyone was seated. Dr. Jones. Dr. Ramirez. Dr. Denard. Dr. Hall. There was a blur of specialists, a handful of nurses, a couple of psychologists and some pre-med students. Inconsequential formalities. My heart was pounding again. I tried to swallow, but my throat was dry.

The professionals spoke. “Your son.” A son! Son. “Severe heart defects.” Their mouths moved but the words were muffled. Muted. The cold, rawness of the first words spoken “Your son. Severe. Heart. Son. Defects. Son. Severe. Son,” skipped like a scratched vinyl record. “His chances of survival through the birthing process are next to none, if he lives that long. Upon birth he’ll need an immediate heart transplant only possible in select hospitals thousands of miles away. You’d have to relocate for quite some time. That heart may be rejected, that is if we can find a heart for him. He’ll need more transplants as he grows. Chances. A son. Survival. Immediate transplant. Relocate. Thousands of miles. A son rejected.” For what seemed like an eternity, the whirlwind was spinning. And then it stopped.

The room held a thunderous silence. I looked out at the blank faces staring back at me. I felt so small. Why couldn’t they make my decision? Why did it have to be me? I opened my mouth to speak, but my voice cracked. Breathe, breathe, breathe, I told myself, clearing throat again. “I want to terminate my pregnancy.”

I said it. Said the words I did not want to say. But knew I had to. The words I had prayed to receive. And then I heard the sighs. Sighs of relief. Escaping the mouths and hearts of everyone in the room. Sighs offering me comfort about a decision well made. We left the hospital. Silenced. Dispirited. I would return to the hospital at 9:30 the following morning to voluntarily end the life of my child.

We’d stayed at the same hotel, a year prior, during my husband’s heart surgery. It felt comfortable. Homey. They addressed us by name, and we were treated well. For me, the hotel held many memories. My first experience there had been a private party with a rock band on their world tour. Then a “Bride-to-be” wedding gala and the list goes on. It was a place where the infamous and “B” actors stayed while shooting on location. Falling in to conversation with them in the elevators or the lounge happened all the time. To be honest, the sheer retail therapy available; shopping at close proximity and bag drop at my fingertips, would’ve been a draw. But that night, thoughts so banal, didn’t enter my mind.

They gave me drugs to aid my sleep that night and maybe I did. Don’t know. Had to remind myself to breathe. Just breathe. Deeply. Inhale. Exhale. BREATHE. Faith Hill’s lyrics ran through my head, “Caught up in the touch, the slow and steady rush. Baby isn’t that the way love is supposed to be? I can feel you breathe. Just breathe.”

Unable to sleep any longer, it was early the next morning, when we went downstairs for breakfast. Happier times had been had in this very restaurant for us. This not being one of them, and well aware I’d need superhuman strength for the self-administered labour, I ordered Eggs Benedict.

Nearby a man and a woman sat together, laughing over their coffee. I’d never been so desperate for a laugh, myself. But her laugh was so familiar. Familiar enough to make me look up. And I realized it was the actress who had played Marion Cunningham, the perfect mother from the television show, Happy Days. How many hours of my childhood had been spent, after school, sprawled on a bean bag chair enjoying the Cunningham family and their antics, while my parents were away at the Cancer Clinic? It is then I smiled. Because, like some kind of surrogate mother who had been there for me before, she made me feel safe. She’d no clue about who I was. Of the trauma I was facing. Nor how, at that moment, she gave me, in a small way, a glimmer of hope.

When it was time, we drove to the hospital. I needed to take anything and everything I could from this moment. I needed to remember every detail. I wanted my senses to never forget. With chunky crimson red boots, I was again wearing my camouflage dress. It wasn’t a maternity dress. Simply a stretchy form fitting, high necked, short sleeved, three quarter length dress. Of ever so slightly see-through fabric. I felt good in this dress. Even though it was the same dress I had on when they told me the news. Out of what I was about to experience, I was desperate to accentuate any ray of light I could. And if some trivial piece of fabric could boost my senses even an iota, I was going to take it.

Hand in hand, we walked through the doors. The only brightness in a flatly lit room were the walls lined with colorful paintings and clay works by young children. The smell was that ever present hospital smell. Clinical, yet sort of stale and so familiar from my past, that oddly I found some comfort in it. Behind a desk, where we would register, sat two ladies. One was on the telephone. I’m pretty sure her unlucky colleague was wishing she’d been the one on the telephone too, after she greeted us with an appropriate, “Good morning. Can I help you?” “Uh yes, I am here to…” Someone stepped in for me, as I broke down. We were then ushered to an elevator.

Stepping out, we turned left twice, circumnavigating a maze of linen carts in the hallway to the room where I would give birth to my son. A room that felt forgotten. Obscure. Hidden. It was like a place to hide a dirty little secret. Inside, medical instruments hung on its walls which were white. The bedding was bright on a lone single bed. There were dismal peach coloured drapes around a window with no view. The room was brighter than its small, dull and grey bathroom with just a toilet, sink and an emergency pull cord.

The alternatives to inducing my labour had been discussed and it was agreed that I would take part in a study. Meaning, throughout the day, I would insert a series of pills. Vaginally. Labour to ensue. And like the beginning of a bad joke, a couple of doctors, an intern and two nurses entered the room. After signing the forms, I was handed a package of pills and told to go into the washroom to insert one. I was then told I could leave the hospital, but not to venture far. In case my labour came on too quickly. And oh yes, try to keep calm. In a daze, and for lack of anywhere else to go, we hit a nearby shopping mall. Aimless, we wandered the halls, to buy nothing. Looking, we saw nothing. Listening, we heard nothing. Thinking, we tried hard not to feel. My emotions were so contradictory, so raw. Wanting to experience everything, and at the same time, nothing.

Blessed with a high pain threshold, the intensity I am capable of enduring is legendary. To my amusement, after our first child, my husband said, “I’ve a new respect for you. Bet I could take an axe to your leg and you wouldn’t flinch.” That labour lasted thirty-nine and a half, (Can’t miss that half) hours. And except for short intervals, with all I had, I was pushing for four. Well this was no different.

Soon enough, mental torment became secondary to physical agony. The pills were working.

And this labour began with a vengeance. Because this baby wasn’t entering our world to stay, I’d expected the labour to be less severe. But I couldn’t have been more wrong.

My husband wanted to return to the hospital, because the labour was so severe, but I insisted we keep walking. Non-contracting moments were filled with emotion. I wasn’t ready to say goodbye. Not yet. Didn’t want to lose this feeling of my son inside of me. Didn’t want to lose part of myself. I wanted to continue talking to him. Playing with him. Moving his little body about me and rubbing love all over him. Desperate, I didn’t want to let go of the hopes and the dreams. I didn’t want to make my decision a reality.

Excruciating, when the contractions came, my head went somewhere else. Breathe, Breathe, Breathe. I was stubborn. I would not go. Not yet. We walked out to the truck, where I couldn’t stop crying. Looking at my despondent husband, I knew it was he who could take no more.

I didn’t care. Body and soul, I was in my finest form, with no intention to vacate either. And loving myself pregnant, the occasional whimper escaped me, but louder was the emotional pain. We drove back to the hospital parking lot, only to sit in the truck for as long as I could convince him to stay. Walking back through those doors, going up in the elevator, and down the dingy hallway, again we skirted around the linen carts and entered the white room in the hospital’s most remote corner. Pausing every 45 seconds or so to breathe through the pain, indeed we had succeeded in arriving. To my son’s birthplace, where he would also die.

I wasn’t dilating. The nearby nurse monitored my progress and though attentive, my husband was terrified. Now clothed in a dreadful blue hospital gown, I lay in the white linen of the bed, trying to find calm. Embracing these last moments with the child within and praying for the strength to deal with it all. Breathing through the pain that would not give me a moment’s peace, as hour after hour flew by and yet, time stood still.

Nurse on one side and husband on the other, I was escorted to the washroom numerous times, to relieve the enormous pressure on my poor bladder. In my modesty pleading that they leave me alone. Time and again the routine was the same. Until the last time which differed, in that as I sat down, the labour pains came. Breathe. Breathe. Breathe. I had an urge to push, just as a wave of nausea washed over me. I wasn’t sure how much longer I could do this. Was I supposed to push? At that moment my world changed.

“Oh my God! What is happening to me?” Feeling something. I screamed, “Help me, help me, someone, please help me! God, help me!” Between my legs, I saw my son’s small hands grasping at my legs. He was out. He was flailing beneath me. I only heard my own screams. “Anyone. Somebody hold me. Take me away. I need to die now. He’s alive. He’s not supposed to be alive. Oh my God, what have I done?” In seconds the nurse and my husband were there. Alarms sounded, and people came running.

Told to hold my baby, that they might get me back in bed, I didn’t want to. I couldn’t touch him, I was afraid. Managing to get me and my son onto the bed, they then cut the umbilical cord. I so wished the noise in this hospital would stop. Not realizing the noise was me, screaming.

The life that called my body home had moved out. After no more than a few minutes of chaos everyone left, and I lay there alone. Empty. Hollow.

Dismal and omniscient, the peach-coloured curtains were now closed. And as though choreographed, a dark grey shadow cast itself against them, making the room more muted and mundane than before. It was like the natural light of a foggy day and this broken only by a tiny beam of electric light coming from beyond the bathroom door. Where moments before, I’d borne my son. The blue gown I wore was wet. Blood-soaked, it lay limp and lifeless over an abandoned abdomen, and almost as dreadful was a deafening silence that echoed between the four walls of my room. Tormented I asked myself, “Why was my child moving? Why was his heart beating? Why was my son alive?”

The door to the hall opened and there he stood. My husband. With a nurse, he entered the room. Holding my son. Swaddled in the satin and flannel blanket his Grandma had made just for him. Taking the baby in to my arms, I wept. My soul ached with so many questions that still went unanswered. I had to stay in the moment. This one moment in time I knew would end without any kind of closure. There would be nothing more than this.

We spent the next three hours alone with our son. His small chest was moving rhythmically but with no breath. I held him and told him stories of his sister and the life he would have had. Pum pum. Pum pum. Pum pum. He was perfect. Small, but perfect, and his skin was slightly transparent. He had little fat on his body. His heart continued to beat and mine was beating faster. His long delicate fingers wrapped around mine as I held him. I tried to make each and every piece of him a photograph in my memory, a keepsake of my son. A son I would never see again. Pum pum. Pum pum. I apologized to him and told him how much I loved him. He had the sweet aroma of all newborns. That scent bottled, would be an immediate success. Why wouldn’t his heart just stop beating? Damn. Why wouldn’t mine?

We lit a candle, named our son and the hospital’s pastor blessed him. I felt peace for a moment. However, that peace was short lived. Quickly kyboshed, it was absorbed by one resounding question. A question lurking, to which I needed an answer. Due to severe heart defects, I had made the difficult decision to end my son’s life. Yet he’d been born with a beating heart, and three hours later as I loved him in my arms, it continued to beat.

That day stands alone for leaving me emptier than anything I’d ever encounter. Equipped only with my previous life experiences, I’d entered an unknown abyss, and come out hollow, yet grown. And I didn’t want to belong to this. Nobody asked if I wanted to be a member. But that was the day I joined another club.