As events in Ukraine demonstrate, ineluctably, war diminishes our humanity, possessing men – and mostly men – of a callous disregard for life, and a capacity for often inexplicable cruelty.

As such, the invasion of one state by another without a casus belli – as we have witnessed in Russia’s essentially unprovoked invasion of Ukraine and also with the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and other incursions since – has long been considered an injustice: any aggressor thus bears a level of responsibility for what follows.

This does not, however, absolve an injured party from guilt for mistreatment, or worse, of prisoners of war, or other breaches of the Geneva Convention; notoriously described as ‘quaint’ by George W. Bush’s Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, with apparently horrifying consequences.

Sabrina Harman poses for a photo behind naked Iraqi detainees forced to form a human pyramid, while Charles Graner watches.

A Single Murder

In peacetime the violent ending of a single life is newsworthy, but during a military conflict the deaths of thousands are often defined as mere casualties, calculated to diminish one side or another’s capacity to wage war. A cold-blooded logic often underpins such strategic analysis.

‘What was a single murder’ Stefan Zweig asked of World War I, ‘within the cosmic, thousand-fold guilt, the most terrible mass destructive and mass annihilation known in history?’

Beyond the mindless trench warfare of World War I, the twentieth century also produced the exquisite evils of World War II, when the carnage reached the civilian sphere as never before; the leading industrial nations harnessing advanced technologies to produce Concentration Camps, Gulags, carpet bombing, and of course – supposedly bringing wars between Great Powers to an end – the atomic bomb.

In that war’s wake there emerged a new understanding of international law, previously dominated by an insistence that this should only apply between states, as opposed to allowing individual rights to be enforced against officials of an offending state in a foreign jurisdiction.

This traditional understanding was emphasised by a British official during negotiations prior to the Treaty of Versailles after World War I: ‘The new League of Nations must not protect minorities in all countries,’ he complained, or it would have ‘the right to protect the Chinese in Liverpool, the Roman Catholics in France, the French in Canada, quite apart from the more serious problems such as the Irish.’

According to Phillipe Sands: ‘Britain objected to any depletion of sovereignty – the right to treat others as it wished – or international oversight. It took the position even if the price was more injustice and oppression.’ [i]

But the depravities of World War II changed the global mood, even if Hermann Goering could persuasively assert that ‘the victor will always be the judge and the vanquished the accused.’ Indeed, there is a reasonable argument that Russian, American and British officials should also have been in the dock to account for what occurred in Katyn, Hiroshima, Bengal and elsewhere.

Nonetheless, the universal ambit of human rights was one of the great advances of the post-Second World War period, culminating in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In theory at least, it was no longer permissible for states to act with impunity even within their borders, as the Rule of Law gained universal jurisdiction, at least where atrocities were concerned.

Looting of an Armenian village by the Kurds, 1898 or 1899.

Genocide v. Crimes Against Humanity

Thus, charges of Crimes Against Humanity and, arguably more problematically, Genocide, were laid against leading Nazi at the Nuremberg trials.

Coincidentally, the two Polish-Jewish jurists Raphael Lemkin and Hersch Lauterpacht responsible for developing these novel concepts both studied in the University of Lwów, a Polish city between the Wars, before being annexed by the USSR at the end of World War II. Today Lviv, as it is now called, is the main city of Western Ukraine.

Amidst accusations of war crimes, including that of Genocide, being levelled against Russia, it is worth considering important distinctions between Crimes against Humanity and Genocide.

The author of the former concept, Hersch Lauterpacht argued that ‘The well-being of an individual is the ultimate object of international law.’ In contrast, in his 1944 book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe Rafael Raphael Lemkin adopted an approach which aimed to protect groups, for which he invented the new crime of ‘Genocide.’

In response, Lauterpacht worried that the protection of groups would undermine the protection of individuals. He challenged the ‘omnipotence of the state,’ suggesting atrocities against individuals should be referred to as Crimes Against Humanity, whereby no longer would officials from any state be free to treat their people with impunity.

Lemkin also wrote of the misdemeanours of the ‘Germans’ rather than the Nazis, arguing that the ‘German people’ had ‘accepted freely’ what was planned, participating voluntarily, and profited from their implementation. This was similar to the War Guilt Clause contained in the Versailles Treaty after World War I, which was deeply resented by Germans.

Genocide concerned acts ‘directed against individuals not in their individual capacity, but as members of national groups.’ For Lemkin Germany’s terrible acts reflected a militarism born of the innate viciousness of the German racial character. He selectively included a quotation from Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt who noted that one of Germany’s mistakes in 1918 was to ‘spare the civil life of the enemy countries’[ii] and that one third of the population should have been killed by organised under-feeding, but not all Germans shared this mentality.

Collective Guilt

The difficulty, therefore, with the crime of Genocide is that in purporting to protect one national, ethnic or religious group it often implicates another via its ruling authority; this may perpetuate racial stereotypes, such as innate viciousness, and contains a potential for indiscriminate reprisals, or even further wars.

Under the original conception of the crime of Genocide, any Russian, even an expatriate opposed to Putin, might be held responsible for the conduct of the Russian army in Ukraine. This idea of collective guilt – a species of Original Sin attached to a national or racial group – generally based on supposedly timeless national characteristics, could also permit crippling sanctions and even bombing campaigns impacting on civilian life.

Punishing an entire nation for the conduct of its government – even if that government is democratically elected – is therefore unjust, not least as it tends to bolster the authority of belligerent elements within a state – who may point to the aggressor posture of the opponent – diminishing the likelihood of lasting peace.

Far less problematic is the idea of Crimes Against Humanity, which simply asserts a universal jurisdiction for atrocities committed by the officials of any state, including ‘legally’ against their own people.

But charging Russian officials with Crimes Against Humanity might lead us to consider whether the leaders of other nations, including the US – which along with Russia (and Ukraine) is not a party to the International Criminal Court – should be similarly indicted.

Drone Strikes

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century the US has been waging warfare through extra-judicial assassination operations: drone strikes, aimed at suspected ‘terrorists’ living in some of the world’s most deprived and defenceless countries. As of 2021, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism claims that there have been at least 13,072 confirmed drone strikes on Afghanistan alone since 2015.

These remote attacks represent a new phase in the cruelty of warfare, as the leading Superpower maintains a social distance from each hit. The consequences, or ‘collateral damage’ is rarely investigated by a mainstream media that now howls in anger at Russia’s excesses.

As LSE’s Maarya Raabani puts it: ‘Buoyed by mainstream media, an alarming preponderance of metaphors and passive-voice reporting have denied any chance to hold drone atrocity perpetrators to account.’

Moreover, ‘Drone strike casualty estimates are substituting for hard facts and information about the drone program,’ said Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School. ‘These are good faith efforts to count civilian deaths, but it’s the U.S. government that owes the public an accounting of who is being killed, especially as it continues expanding secret drone operations in new places around the world.’

In July 2021, U.S. President Biden announced the adoption of an ‘over the horizon’ counterterrorism strategy. According to the Brookings Institution:

The new plan would rely on armed unmanned aerial vehicles — or drones — to respond to terrorism threats around the globe without deploying American boots on the ground. But although the strategy was designed to overhaul policies that had kept the United States embroiled in conflict for 20 years, it failed to address the unintended consequences of counterterrorism strikes, namely civilian casualties. On August 29, 2021, with most U.S. soldiers withdrawn from Afghanistan and regional bases shuttered, this challenge became clear. The U.S. military conducted a strike that killed 10 civilians, including women and children, rather than the intended target.

TAS13: GENOA, JULY 22. Russian President Vladimir Putin (left) and US President George Bus.

In striking unison, mainstream media in the West has reacted to the invasion of Ukraine with outrage, and conveyed statements of the President of Ukraine with uncritical approval. Russia certainly deserves opprobrium for his war of aggression against Ukraine – and its officials may be responsible for war crimes – but the failure to interrogate the actions of the US and its allies including Israel and Saudi Arabia over many years makes the self-righteousness ring hollow.

Russia is operating in a context established by the US’s illegal invasion of Iraq in 2003 that destabilised the Middle East causing hundreds of thousands of unnecessary deaths. Putin exploited the anarchy in the international system with his invasion of Georgia in 2008, having divined that the rules of the game had changed. There is a continuum between Russia’s attacks against Georgia, the Donbass and Crimea campaign in 2014, and this latest invasion of Ukraine.

Once Western leaders and their allies are also held accountable for their actions we may move to an environment where the Rule of Law attains a universal character; then the invasion by one state of another without a legitimate casus belli may become unthinkable.

Unlike during the period of the USSR, Russia exerts little ‘soft’ power. Putin’s propaganda relies on the hypocrisy of the West, especially the US which continues to baulk at becoming a party to the International Criminal Court and allies with rogue actors such as Saudi Arabia and Israel. Confronting Russia should also involve Western governments pursuing morally consistent foreign policies.

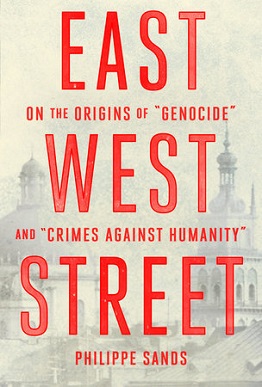

[i] Phillipe Sands, East West Street: On the Origins of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, (Knopf, New York, 2016) p.72

[ii] Ibid pp.82-184