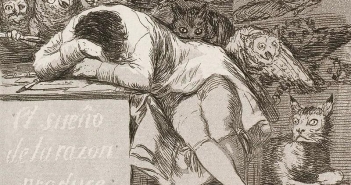

Life, as we find it, is too hard for us; it brings us too many pains, disappointments and impossible tasks. In order to bear it we cannot dispense with palliative measures… There are perhaps three such measures: powerful deflections, which cause us to make light of our misery; substitutive satisfactions, which diminish it; and intoxicating substances, which make us insensible to it.

Sigmund Freud from Civilisation and its Discontents (1930)

One sees it traversing through the garrulous troughs on social media, particularly X (formerly known as Twitter), and in the comments section on YouTube. For example, ‘Dads car,’ and, ‘Mums SUV’, rather than ‘Dad’s car,’ or ‘Mum’s SUV.’

It is time-consuming to learn how to punctuate and, thus, write correctly – adhering to the rules. Many find concentrating on this to be a chore. One comprehends, but… it is unadulterated, plaintive laziness.

This is not ‘Grammar-Nazism’ as the meme-led, cultural clichéd term goes. This is about improving one’s writing, working harder, avoiding inertia and Mediocrity. Many prefer verbal communication and visual stimuli to sitting down to write – in a chair ‘old school’, the traditional way.

An instantaneous gratification culture is alive and well. It descends into a podgy finger flicking on a dimly lit screen of an evening, absorbing those dopamine hits. Bobbing and weaving through the electronic morass. Jiving and twisting. The synaptic twerking of consciousness.

We, as human beings, have become slovenly. Infantilised, as we pig out on junk food. Recumbent and ‘comfy’, as we wade through the internet’s offerings. Night after night.

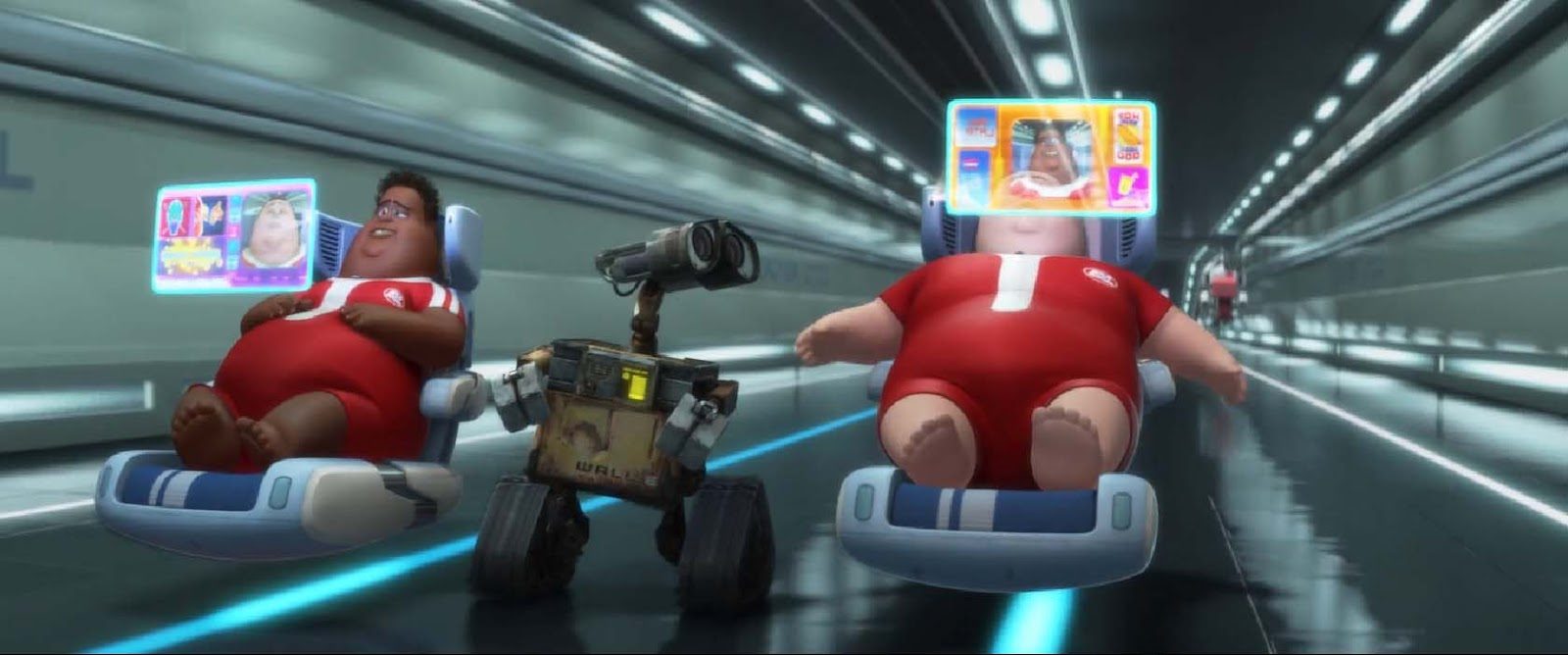

WALL-Es

That scene in the Disney Pixar movie WALL-E with overweight patrons onboard the flying-in-space cruise ship on hover chairs flying around onboard, never walking, watching big screens that tell us when to eat and when to chill. These humans reflect what we have become: our seemingly ambiguous comfort in this obesity has been normalised.

This is where the capitalist market has led us. There is profit in wanton laziness for those who make the products of greed readily available and easy to consume. They do not want to give up that income stream, and into the troughs come the snouts that munch, munch, and munch amidst the squeals.

Shucking up gallons of fizzy drinks. Snuffling down handfuls of sweets and munching upon oil-laden fries. Scoffing on crisps, cakes, and biscuits to fill that sugar, fat, and salt desire, with little or no real nutritional value to help our brains and bodies function.

This writer has been guilty of the above, overeating junk food. It leads to diabetes, heart disease, high cholesterol, and long-term health complications. It is a work in progress to avoid being bowled out at fifty, succumbing to gout, fat-infused valves, and diabetes.

The idea of spending, as one young person informed me of late, ‘the evening/night scrolling through TikTok,’ is a sad indictment of where many have arrived. We delight in the displayed lives of others on the smartphone’s small screen. But is there anything to be learned from this narcissistic intrigue and fascination?

This writer believes there is a correlation between poor diets and sedentary lifestyles. It is about accepting banality as the status quo and not desiring to work harder.

Image: Maria Geller

Mediocrity

Mediocrity, as a movement, is parasitical. It moves onto a host, infects it with its form of banal idealism, and then moves on to the next victim, where it implements the same process. Replication. A bacillus of sorts.

Mediocrity feeds into apathetic mindsets that have been taken over by the synaptic-feed outlay. It encompasses newspapers, mainstream media, and much of what is posted on the internet. It promotes and projects an idealistic self-image. Differences are highlighted and ultimately vilified – leading to racism – day in and day out.

Terms such as ‘Shock’ and ‘Fury’ in online news articles feed into that visceral, tribe-on-alert, emotive response that keeps people in that Sartrean fear of ‘the Other’, compounding accepted, interjected biases.

We are also constantly exposed to false standards of measurement. There is a multitude of inane, beige, loquacious, naive, idealistic, and elegiac minds all desiring the same thing – to be rich and famous.

As Freud states in the opening paragraph of Civilisation and its Discontents: ‘It is impossible to escape the impression that people commonly use false standards of measurement – that they seek power, success, and wealth for themselves and admire them in others, and that they underestimate what is of true value in life.’

Having a million social media followers does not generally bring financial success – it is illusory. These individuals, who are generally beneficiaries of marketing campaigns, have become false prophets. Mediocrity is a virus, burning through media outlets, claiming there is only one way.

Because of its extensive reach and influence, Mediocrity is not readily noticed and thus rectified. It has become entrenched. The indomitable rise of Mediocrity coincides with a fall in proper adherence to punctuation and grammar rules.

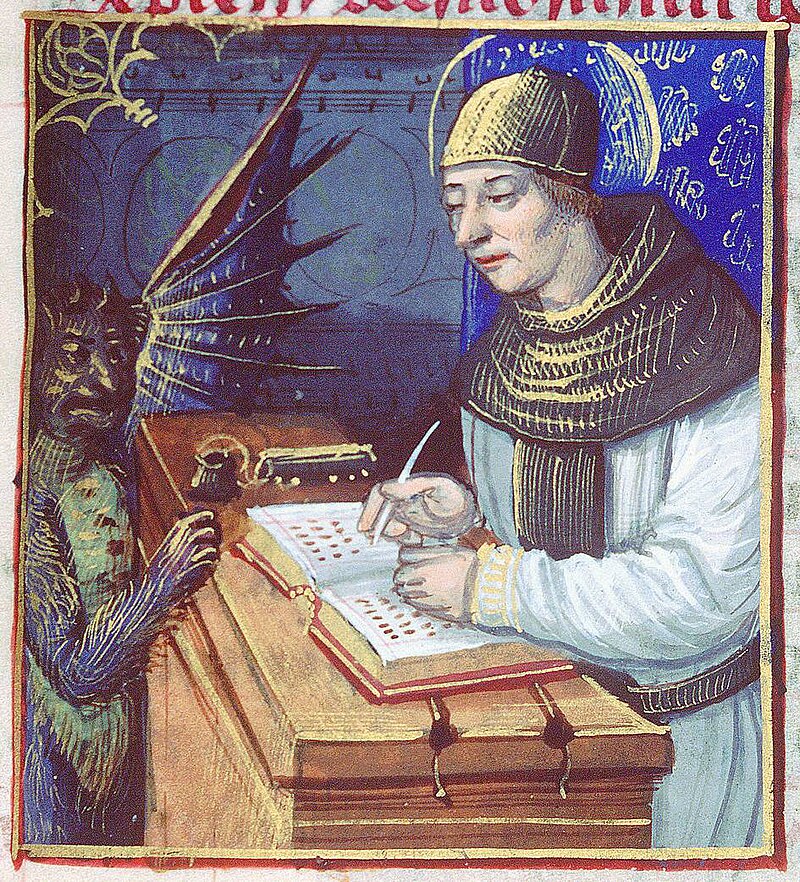

Titivillus, a demon said to introduce errors into the work of scribes, besets a scribe at his desk (14th century illustration),

Punctuation in History

As far back as 260 BCE (Before the Christian Era) in China symbols were being used as full stops on bamboo texts to indicate the end of a chapter. Around this time, Western scholars used scriptio continua, text with no separation between the words. The Greeks were using punctuation marks consisting of vertically arranged dots from the 5th century BC as an aid to oral delivery. After 200 BC, the Greeks used Aristophanes of Byzantium’s system (called théseis) of a single dot (punctus) to mark up speeches.

In addition, the Greeks used the paragraphos (or gamma) to mark the beginning of sentences, marginal diples to mark quotations, and a koronis to indicate the end of major sections.

To take two forms of punctuation, the comma and the semicolon. The comma is widely attributed to Aldus Manutius, a 15th-century Italian printer who used a mark now recognized as a comma to separate words. The word is derived from the Greek koptein (literally ‘to cut off’).

Meanwhile, the semicolon is first attested to in Pietro Bembo’s book De Aetna (1496). In English it is most commonly used to link (in a single sentence) two independent clauses that are closely related in thought, such as when restating the preceding idea with a different expression.

Among great exponents of punctuation, essayist Thomas Carlyle’s 1829 paper ‘Signs of the Times’ employs commas, semicolons, and dashes to break up his sentences and usher in and connect content. Similarly, Herman Melville’s divine usage of the semicolon in his seminal 1851 is evident throughout his almost biblical, classic Moby Dick.

A semicolon can waver back and forth like the tail of a young fry salmon, or a whole raft of them can glitter and flip like sardines caught in a net. A semicolon can work like a wooden gate, allowing the woolly sheep of greater meaning to enter greener pastures, enhancing the experience of reading.

I notice online that some scholars believe that semicolons are pretentious and overactive. So, is this writer just cribbing the numbskulls of opacity? Are we in a fugue state? A place of unlimited bohemianism. Or am I mixing aphorisms?

There are rustling hedgerows of commentators who draft in writers such as James Joyce, saying he ‘kept punctuation usage to a minimum.’ Maybe for Ulysses, but please do not allow yourself to be locked up in the one house of another writer’s style for justification and throw away the key. This is how a particular style becomes overgrown, with mossy banks, thorny thickets, and crabgrass obscuring the view.

I recall a history lecture where the American lecturer said that commas in an academic essay amounted to a crime. This may be true of an academic paper which is dedicated towards a particular arguments that employs texts to make it, but not in a more literary style.

Gertrude Stein seemed to take umbrage at ‘unwarranted’ punctuation with her grandstanding as a grammarian. She was the one who did the heavy lifting in terms of criticism – employing an academic register in her prose to disenfranchise good punctuation usage further. Stating: ‘I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences.’

If we embark upon this model, this mentality, we enter a Stygian process – one that slips off the banks and bobs on down to the underworld – into a void of immutable darkness and further self-perpetuating ignorance.

You see punctuation can give writing its function. That is a litany of small symbols denoting how that particular nuanced form acts or functions. A sentence can be a sentence, but punctuation can jolt it into life. Some may say it is a question of style. I say it is a question of slovenliness in an age of electronic meandering.