In 2015, documentary filmmaker and Director of Loopline Film, Sé Merry Doyle, and the Irish Film Institute, received funding from the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland to archive the company’s collection. Over a twelve-month period, Sé and I fully catalogued 16mm and 35mm films, tapes in a variety of formats, and numerous audio materials. These were simultaneously preserved and digitised at IFI Film Archive.

The Loopline Collection comprises some thirty-eight titles made over its thirty-five-year lifespan. There are full documentaries and TV series as well as previously unseen pilot materials for projects that, for one reason or another, never got the green light. These outtakes are the vein of gold running through the collection.

The most accomplished works, in my opinion, are the full-length biographical documentaries on Irish artists: ‘John Henry Foley – Sculptor of the Empire’ (Sé Merry Doyle, 2007), ‘Patrick Kavanagh – No Man’s Fool’ (Merry Doyle, 1994), ‘James Gandon – A Life’ (Merry Doyle, 1996), and ‘Patrick Scott – Golden Boy’ (Merry Doyle, 2003).

Later films focus on journeys made by artists across geographical and emotional frontiers: ‘John Ford – Dreaming the Quiet Man’ (Sé Merry Doyle, 2011) and ‘Jimmy Murakami – Non-Alien’ (Merry Doyle, 2014). Other productions deal with the issue of Irish Republicanism as seen from the female perspective: ‘Mairéad Farrell – an Unfinished Conversation’ (Martina Durac, 2014), ‘Kathleen Lynn – Rebel Doctor’ (Merry Doyle, 2011), and the series ‘Mna an IRA’ (Durac, 2012).

Working-class life in Dublin is a prominent theme. The 1984 observational documentary, ‘Looking On’, focuses on efforts by artists and communal activists to highlight the inner city community’s struggle against property developers and Dublin Corporation. It’s a theme taken up and developed in later works: ‘Essie’s Last Stand’ (Liam McGrath, Merry Doyle, 1999), the elegiac ‘Alive-Alive-O – A Requiem for Dublin’ (Merry Doyle, 1999), and in rushes for a proposed documentary on the regeneration of Ballymun in 2004 – which, sadly, was never completed.

Expressionist Art in Ireland

Working through the materials, I was struck by Merry Doyle’s persistent exploration of expressionist art in Ireland, a subject scarcely touched on in Irish documentary. His extraordinarily intimate portrait of artist Patrick Scott, ‘Golden Boy’, traces the development of expressionist art in Ireland since World War II.

Similarly, ‘Lament for Patrick Ireland’ (Merry Doyle, 2010) depicts Irish-American artist Brian O’Doherty’s artistic response to the Northern Ireland conflict. Rushes for another Loopline series, ‘Soiscéal Phádraic’, look at art exhibitions by modernists Scott and Robert Ballagh.

One of the most ambitious of several unfinished projects is the substantial footage shot between 1999 and 2007 for ‘Outside Looking In’, a planned documentary series on the impact of modernist art on Ireland. The unseen rushes focus on architects Scott-Tallon-Walker, and artists Robert Ballagh, Dorothy Cross, Michael Cullen, Louis Le Broquy, Ann Madden, Patrick Scott, Sean Scully and Corban Walker.

‘Outside Looking In’ also features a detailed report on the ‘Breaking Ground’ art retrospective exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in 2000, which includes a fascinating interview with then-Director, Declan McGonagle. There are filmed reports on Irish artists Annie Tallentire and Katie Holton representing Ireland at the Venice Biennale in 1999 and 2003; an item on video installation artist Willie Doherty; and audio of Seamus Heaney reading two poems written for his late friend, architect Robin Walker (the subject of Merry Doyle’s latest award-winning documentary, ‘Talking to My Father’).

Watching this material, I was reminded of Merry Doyle’s passion and commitment to his projects through the years. He deserves enormous credit for putting together this significant collection of materials for future artists and art historians.

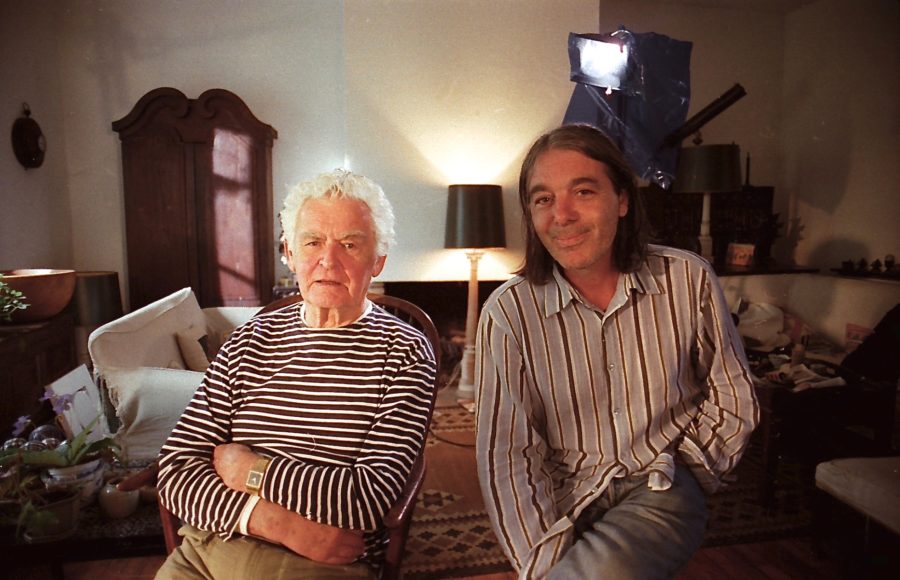

Patrick Scott with Sé Merry Doyle.

Dublin’s Popular Music Scene

For those interested in the popular music scene in Dublin from the 1980s to the present, the collection contains some intriguing items. Outtakes from ‘Looking On’ feature unseen footage of 1980s bands The Atrix and Hotfoot and an early impromptu rooftop show in Sheriff Street by U2.

U2 on Sheriff Street. Photo courtesy of Christine Bond.

Rushes for an unedited tribute concert staged by friends and fellow musicians of guitarist Jimmy Faulkner at the Olympia Theatre in 2008 capture the full show (filmed with four cameras) with performances by Paul Brady, Christy Moore, Mary Stokes, Declan Sinnott, Noel Bridgeman, Ed Deane, Don Baker, Honor Heffernan and others. The show is compered by musical impresario Smiley Bolger and politician Eamonn McCann, and the rushes contain informative and amusing backstage interviews about the Dublin music scene from the 1970s to the millennium.

Other musical treasures include audio rushes of the soundtracks composed for the later documentaries by multi-instrumentalist Ger Kiely and complete audio takes of traditional Dublin ballads sung by musicologist Frank Harte for ‘Alive-Alive-O’. These are records of a vibrant, but largely unexplored, Dublin music scene.

Frosty Interview

Going through the tapes, it became obvious that some of the finished documentaries could have been further enhanced by more extensive use of the rushes. We can see, in retrospect, that the requirements of TV scheduling put constraints on the running times of the documentaries.

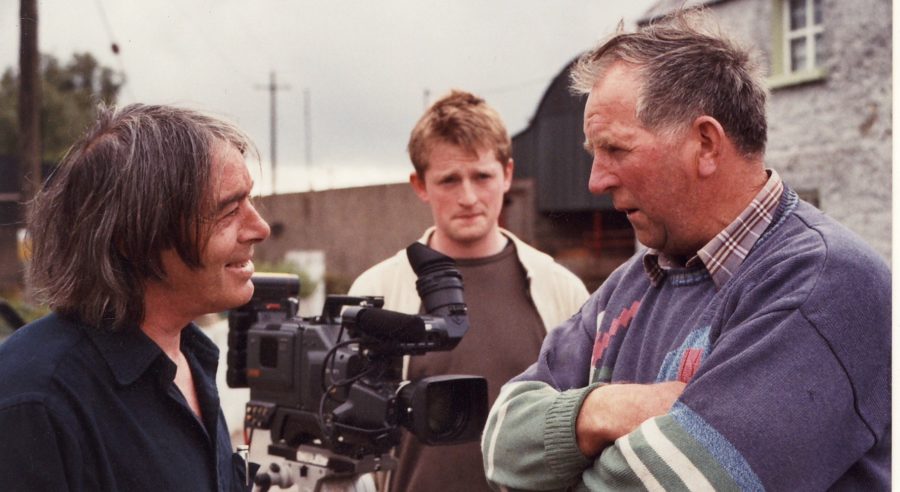

It’s one of the great benefits of this particular archive project that that these outtakes can now be encountered and enjoyed as stand-alone pieces. For example, Merry Doyle’s personalised portrait of poet Patrick Kavanagh, ‘Patrick Kavanagh – No Man’s Fool’, is heartfelt and full of intimate moments, but the outtakes flesh out the story considerably. There are in-depth, previously-unseen interviews with actor T.P. McKenna, author Dermot Healy, poet John Montague and other people close to the poet.

A fascinating sequence with Kavanagh’s brother, Peter, at the installation of a plaque at Parson’s Bookshop on Baggot Street, sheds light on the controversial relationship of the siblings. Audio recordings of actor Gerard McSorley’s beautiful readings of Kavanagh’s poems, only partially used in the film’s final cut, emphasise the genius of both actor and poet.

Writers Dermot Healy and Leland Bardwell perform a wonderful dialogue on the subject of Kavanagh’s women at the Model Arts Theatre, Sligo. A hitherto unseen lecture on Kavanagh by poet Paul Durcan at a Carrickmacross hotel is affectionate and funny.

On location, ‘Patrick Kavanagh – No Man’s Fool’.

The same can be said regarding the rushes for the historical biography, ‘James Gandon – A Life’, which feature lengthy interviews with the late architect Sam Stephenson, art historian Edward McParland, and conservationist David Slattery.

There’s a wonderful guided tour of Gandon’s architecture along Dublin’s River Liffey by art historian Maurice Craig, which was not included in the film and comprises a colourful history lesson in itself. The rushes for the scenes in which veteran Irish actor Christopher Casson plays an ageing Gandon show him engaged on the final work in his distinguished career. One of the best things here is a spectacularly frosty interview with former Taoiseach, Charles J. Haughey at his Gandon-built home, Abbeyville, in North Dublin.

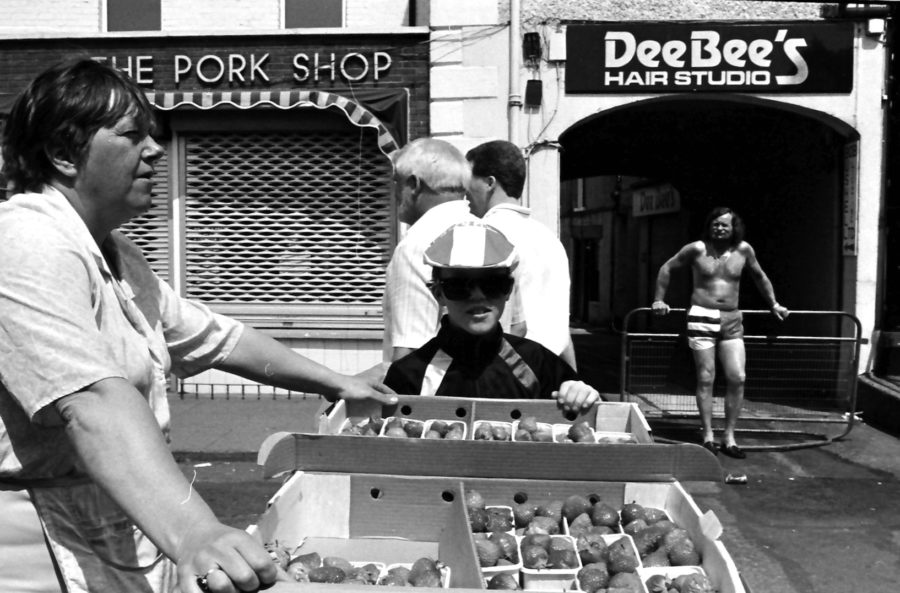

Street Traders

The copious rushes for one of the finest Loopline productions, the personal and impressionistic ‘Alive-Alive-O: A Requiem for Dublin’, are astonishing. They encompass an unprecedented record of the suppression by the state of Dublin’s traditional street traders, the closure of marketplaces, the heroin epidemic that devastated the inner city communities in the 80s, and the work of TDs and social activists in defending the workers livelihoods.

Among the outtakes is interview with the the fiercely articulate late T.D. Tony Gregory. The collection also has lovely audio recordings of actor Jasmine Russell reading commissioned verse by contemporary working-class poet, Paula Meehan.

Supporters of Tony Gregory. Photo courtesy of Derek Spiers.

The rushes for ‘John Henry Foley – Sculptor of the Empire’ are equally detailed and rich. They feature, for example, lengthy interviews with sculptor Cliodhna Cullen, art historians Paula Murray and John Turpin, Senator David Norris and then-Director of the National Museum, Pat Wallace.

Also contained herein are extended rushes of two intriguing journeys: one to Cambridge, England, where Foley’s statue of General Hardinge, once proudly displayed in Ireland, now stands in a relative’s country garden; and another to Barrack Pore in Calcutta, India, a cemetery for decommissioned imperial statues. The high production values of the finished documentary are reflected in the breadth and richness of these rushes.

Watching the outtakes of ‘Patrick Scott – Golden Boy’, one becomes aware of the closeness between director Merry Doyle and Scott. In a lengthy week-long interview, the modest, Zen-like Scott reflects on his career in an Ireland inimical to non-representational art.

There are many interviews never used in the final cut with people such as art critic Bruce Arnold and others intimate with Scott. An interview with Scott’s friend, the late poet Seamus Heaney, is of particular interest. Merry Doyle has done Scott an enormous service in recording this material for future generations. It all amounts to a truly compendious overview of the history of modern art in Ireland.

Folk Art

‘Hidden Treasures’ (Anne O’Leary, 1998) is a four-part anthropological series looking at Irish folk-life. It was structured around 16mm field recordings of traditional rural crafts made by the National Museum of Ireland from the 1950s to the 1970s, which Merry Doyle had restored and digitised before inviting folklorist O’Leary to direct.

The series focuses on man’s relationship with the sea, traditional agricultural tools and technologies, and the role of ritual in rural life. Haunting colour footage shot by cinematographers Brendan Doyle and John T. Davis throughout rural Ireland complements this early archive footage and the rushes add up to a beautiful folklore archive in themselves.

Like its companion piece, the one-off Christmas documentary, ‘Ó Bhéal go Beal um Nollag’ (Durac, Vanessa Gildea, 2010), ‘Hidden Treasures’ provides a final glimpse of quickly fading traditions. (Incidentally, this was not Merry Doyle’s only foray into film archiving. He was also responsible for the 1996 restoration of ‘O’Donoghue’s Opera’ (Kevin Sheldon, 1965), a lost film featuring The Dubliners, and Peter Lennon’s 1968 documentary, ‘The Rocky Road to Dublin’.)

One of the finest Loopline productions, ‘Jimmy Murakami – Non-Alien’, is a moving account of the animator-director’s attempt to reconcile the events of a troubled childhood by journeying from his adopted home in Dublin back to the site of trauma – Tule Lake, California. There his family were incarcerated in a Japanese-American concentration camp during World War II.

JImmy Murakmai at Tule Lake.

As in the Scott portrait, the rushes here reveal Merry Doyle’s close relationship with his subject (he and Murakami had been friends for years before the film’s production). While the film itself is a moving account of Murakami’s spiritual journey, the rushes show the ways in which Merry Doyle attempts, over many takes, to get to the core of his friend’s emotional conflict.

While Murakami drives along a Californian highway at sunset, Paddy Jordan’s camera captures perfectly the emotions coming to his face, as producer Vanessa Gildea sobs in the back seat of the car. As the journey comes to an end, the rushes show how the director’s patience is rewarded by the arrival of an exquisite sunset that permeates the closing scenes.

Sadly, Jimmy Murakami passed away not long after the film’s release, but, as with the Patrick Scott project, Merry Doyle and crew have created a staggering portrait of this unique artist for the generations.

In ‘Kathleen Lynn – Rebel Doctor’, Merry Doyle and crew tell the little-known story of the suffragette, Republican and doctor and her conflict with the independent state in establishing Saint Ultan’s Children’s Hospital in Dublin.

The rushes feature in-depth interviews with feminist historians Sinead McCoole, Loretta Clarke, Margaret Ó hÓgartaigh, author of a book on Lynn, Honor O’Brolchain, historian Margaret MacCurtain, feminist activist and historian Dr. Margaret Ward, medical experts Dr. Barbara Stokes and Dr. Rosarie Barry, as well as a touching interview with 109-year-old Bridget Dirrane, author, Republican and former staff member at Saint Ultans.

The Quiet Man

Merry Doyle’s hugely-ambitious work, ‘John Ford – Dreaming the Quiet Man’ is, like ‘Jimmy Murakami – Non-Alien’, another story of an artist’s journey into the past.

Seven years in the making, it’s Merry Doyle’s imagining of Irish-American film director John Ford’s dream of returning to Ireland to make the film ‘The Quiet Man’ (1952), as well as a conscious attempt to redress the film’s negative reputation on home ground.

With Martin Scorsese (l).

The rushes include a detailed interview with American director, Martin Scorsese, in which he discusses the poetry of Ford’s film and themes of emigration and community. American director, Peter Bogdanovich, talks about his personal relationship with Ford and his deeply-felt affection for The Quiet Man. Dublin-born Hollywood actress, Maureen O’Hara, the film’s female lead, entertainingly reveals her relationships with the difficult Ford, actor John Wayne and her experience working on the film.

In an interview with Jay Cocks at the Algonquin Hotel in New York, the scriptwriter explains how the boxing scene from Ford’s film influenced the ringside scenes in Scorsese’s ‘Raging Bull’. John Wayne’s daughter Aissa talks about how Ford, O’Hara and Wayne struggled to get the film financed. American academics Joseph McBride and William C. Dowling speak almost obsessively about Ford and ‘The Quiet Man’. The rushes also contain some breath-taking footage of Monument Valley, Utah, where Ford shot many of his Westerns, through the lens of regular Loopline cameraman, Paddy Jordan.

Sé Merry Doyle & Maureen O’Hara at The Maureen O’Hara Film Festival, at the Eccles Hotel, Glengarriff, Co. Cork.

Picture: John Delea/Muskerry Photos.

Poetry and Literature

While the collection focuses mainly on the visual arts in Ireland, there is a special emphasis on poetry and literature. An outtake from the ‘Soiscéal Phádraic’ arts magazine series, for example, features an amicable interview with writer John McGahern at the Galway launch of his ‘Memoir’ in 2005.

The popular Imprint series, produced and broadcast between 1999 and 2001, features interviews with national and international writers and is presented by poet Theo Dorgan. Irish writers interviewed are poets Eavan Boland, Dermot Bolger, Anthony Cronin, Brendan Kennelly, John Montague, Michael Longley and Nuala Ní Domhnaill; novelists Leland Bardwell, Maeve Binchy, Roddy Doyle, Jennifer Johnston, Bernard MacLaverty, Joseph O’Connor and Colm Toibín; and playwrights Thomas Kilroy and Hugh Leonard. International writers interviewed are Margaret Atwood, J.G.Ballard, Thomas Keneally, Richard Ford, Doris Lessing, Edward W. Said and Gore Vidal. These interviews have never been seen before in their entirety. An hilarious interview with American writer Kinky Freedman is one of my personal favourites.

The Imprint series also featured especially commissioned short films on poets and writers by new Irish directors: Maurice Healy’s charming short on legendary sports journalist Con Houlihan; Paul Duane’s films on novelists Patrick McCabe and J.M O’Neill; Art O’Leary’s meditation on Dublin’s War Memorial Park; Hilary Dully’s comic take on the poetry of Rita Ann Higgins; Barrie Dowdall’s atmospheric short on Wexford playwright Billy Roach; Donald Taylor Black’s rumination on Russian poet and novelist Boris Pasternak; Brendan J. Byrne’s lyrical and experimental pieces on poet Louis McNiece, novelist Brian Moore and poet Ciaran Carson; Eve Morrison’s visit to the Dublin Inner City Folklore Project; Niamh Barrett on novelist Marian Keyes; Sé Merry Doyle on Charles Dickens in Ireland and his short about Oscar Wilde, ‘Wild About Oscar’; and David Barker on writer Carlo Gebler. The rushes for the Con Houlihan short make for particularly absorbing viewing.

In San Francisco.

Master Class

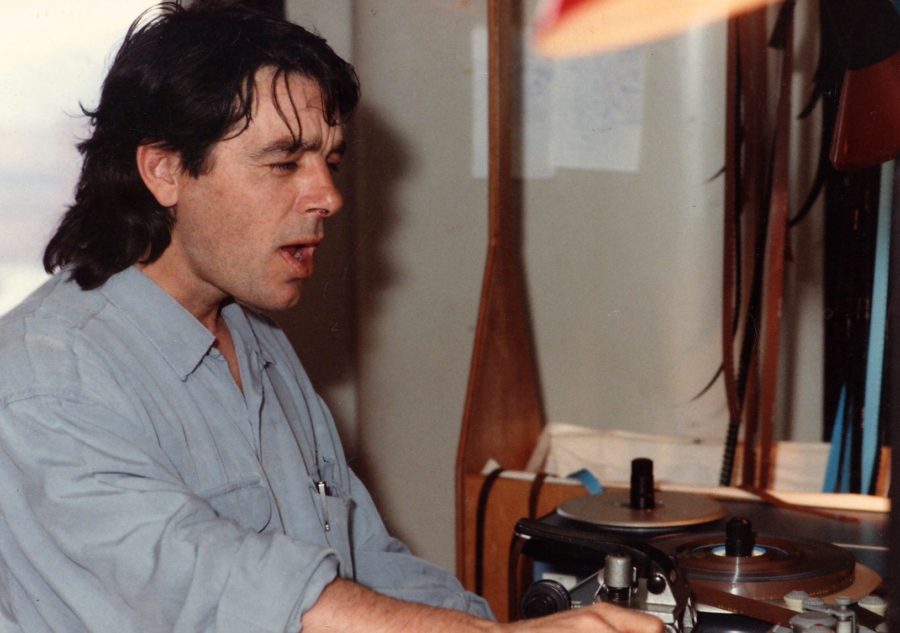

It struck me that the rushes and outtakes constitute a kind of master class in documentary filmmaking. Merry Doyle and crew members are present throughout and the process of filmmaking is often laid bare: the filming of establishing shots; the pursuit of the best takes; the honing in on ideas that arise during interviews; as well as the playfulness of the crew after a successful filming session.

An unfinished project, ‘Documentary Where Art Thou?’, a series of interviews with prominent international documentary filmmakers filmed at workshops funded by Screen Training Ireland, examines the subject of documentary production itself. The interviews are loose and informal, allowing directors Jon Bang Carlsen, Molly Dineen, D.A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegadus, John T. Davis and Peter Wintonick to engage with the nuts and bolts of documentary theory and practice. Russian director, Maria Goldovskaya, is also filmed giving a class on her work as a political filmmaker.

The rushes shot by the Loopline Film crew for projects that were never completed give a clear picture of the traditional difficulties of raising funding for serious cultural documentaries. Watching the footage shot for a projected film on writer Lafcadio Hearn (Greek-born but of Irish heritage), drove home to me how significant and entertaining such a film would have been and it becomes quite obvious that an opportunity had been missed.

The unfolding events are funny and often moving as Merry Doyle’s camera accompanies great-grandson Bon Koizumi and his wife in the footsteps of the writer around Dublin, Waterford and Mayo. The preservation of these materials at the IFI leaves open the possibility that these projects might eventually be completed.

Equally tantalising are the rushes for a documentary portrait of Irish writer, historian and critic, Ulick O’Connor. In retrospect, it’s a shame that Merry Doyle was unable to raise funding to complete the project as the pilot material shows a refined literary mind at work.

O’Connor delivers a detailed lecture on the Irish Literary Renaissance at the United Arts Club in Dublin and gives an eyebrow-raising interview at his Dublin home. At one point he reads from his translation of an Irish-language poem by Brendan Behan on Oscar Wilde’s sexuality. It’s an unknown poem which could be read as Behan’s own coming-out statement (camouflaged, ironically, by the Irish language).

Sé Merry Doyle.

Life Goes On

Abandoned footage (by Merry Doyle and Linda O’Sullivan) for a portrait of the late socialist politician Jim Kemmy, a humanist and visionary, once more indicates the short-sightedness of funders. The rushes outline Kemmy’s trade union work in the 1970s and 80s, his championing of the working-class, his contribution to the anti-apartheid movement, his work on family planning and his battle against the Catholic Church.

Merry Doyle’s pilot material focuses on this important figure through informative interviews with Kemmy’s brother Joe, Labour TD Janice O’Sullivan, and Kemmy’s partner and co-worker, Patsy Harrold. Another incomplete project from 2002 comprises sketches for a portrait of Limerick old-school Republican, Richard Behal.

While the incomplete projects in the Loopline Collection throw much light on the difficulties of raising funding for serious social, cultural and historical documentaries, one can only be grateful for Loopline Film’s commitment and determination to pursue important subjects through creative storytelling.

Thankfully, the IFI and the BAI have been insightful enough to preserve for oncoming generations this broad panorama of Irish social, artistic and cultural life across two centuries. It’s a fitting testimony to the lifelong work and commitment of Sé Merry Doyle and his contributors at Loopline Film over thirty-five years.

Life, meanwhile, goes on as Merry Doyle steers Loopline Film into the future with two fresh projects: ‘John Huston – A Man Without a Country’, the story of American film director John Huston’s adoption of Ireland as a home in the 1960s; and a work-in-progress, ‘Hanna & Me’, the story of Micheline Sheehy Skeffington’s retracing of her great-grandmother Hanna Sheehy Skeffington’s journey to America in the 1920s as a suffragette and political activist.