Out with the old, in with the new. In the same month that Don’t Look Back in Ongar (2024), the final (27th) instalment of the Ross O’Carroll Kelly fictional autobiography was published, the Irish-language musical comedy Kneecap (2024) quickly became the year’s highest-grossing cinema release.

The differences between these two are more than apparent: the ROCK books and newspaper column have given us a satirical history of the south Dublin elite as the country bounces between booms and busts over more than 20 years, while Kneecap is the semi-biographical contemporary story of two working-class Belfast boys who team up with a schoolteacher to form Kneecap, the Irish-language rap group. But it’s also possible to imagine a baton being passed along here, especially when we regard the books and the film in terms of the linguistic shitscape that is modern Ireland.

In the semi-fictional universe of ROCK, the contortions of the English language are the greatest source of comedy, the most pertinent commentary on class and gender difference, and the clearest exposition of Irish culture as being in a state of perpetual colonial aftermath. The bizarre renderings of various accents in ROCK, along with highly convoluted slang, its very narrow field of cultural references, and the characters’ sponge-like acquisition of Americanisms, are a turn-off for many. But they are flattering for readers who, by understanding the linguistic nuances, become themselves the objects of satire.

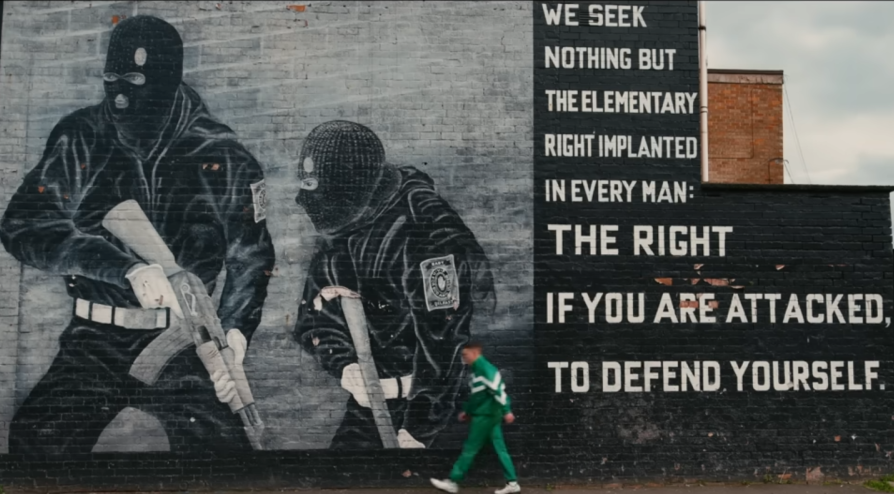

Kneecap is more patently ‘about’ language. In the film itself and in the band’s music and branding (Kneecap is a band in the real world), language is described in the clearest terms as a political issue. The use of Irish, especially in the northern context, is an anti-colonial act – the campaign for the passing of Irish Language Act of 2022 in the British parliament forms the background to the story. Each word is a bullet fired for freedom, according to the mantra of the die-hard pre-ceasefire philosophy of one protagonist’s father (played by Michael Fassbender, who played Bobby Sands in Hunger some years ago). Alongside the fluently delivered postcolonial critique of language and empire, the film also plays on more subtle conflicts of personal battles fought with language – one protagonist whose parents have raised him in Irish and now refuse to speak it to him, another who refuses to speak English when detained by police, and another who hides his Irish-language musical activity from his language-activist partner.

Cultural Divide

These mutual misunderstandings will put ROCK readers in mind of the language barrier that is raised between Ross and his own son, Ronan, who has been raised in Finglas and speaks with a working-class Dublin accent. Now Ronan works in the highest government circles for his grandfather (Ross’s father), the Trump-adjacent Taoiseach. Father and son both speak English, and Ronan always understands Ross, but Ross often just does not get what his son is saying to him:

‘I shouldn’t be tedding you this, Rosser.’

‘You might as well tell me? I probably won’t understand it anyway.’

‘The Gubderminth ren ourra muddy.’

‘They what?’

‘Thee ren ourra muddy.’

‘No, it’s not catching.’

‘Thee.’

‘They.’

‘Ren.’

‘Ran.’

‘Ourra.’

‘Out of.’

‘Muddy.’

‘Oh, muddy! Okay, I get you.’

The joke is partly Ross’s low intelligence, which is what he is referring to at the start when he says he probably won’t understand. Ross is completely ignorant, near-illiterate and unable to focus on anything requiring mental exertion. But he is firm in his self-identity and in the cultural values that count (rugby, private schools, luxury consumption, machismo, etc.). The joke is also of course based on class caricatures, and the working-class characters are treated with as much Swiftian mercilessness as anyone else.

More than Swift, however, the contortion of English in the mouth of Ronan resembles the Joycean madness that descends on the language, on all languages, in Finnegans Wake in particular. When Ronan speaks, the Attorney General becomes the ‘Attordeney Generdoddle’ – and the reader finds themselves in the position of Ross, trying to transform this hibernicized monstrosity back into something comprehensible, back into the language of power. The ROCK books are full of these linguistic breakdowns and anomalies, of characters talking past each other, of language acting as a pick with which to dig even deeper into one’s own trench. The world of the ROCK books, like the language that is spoken in them, is chaotic, controlled by the wrong people, and full of injustices in every chapter. This dark portrait of Ireland, like the best satire, is delivered as a prolonged, stupid, sick, and yet funny, joke.

Naoise Ó Cairealláin with Michael Fassbender in Kneecap.

Labour of Resistance

While the do-nothings in the south live free of the British yoke, the Belfast crowd are working hard at the labour of resistance. Education, self-motivation, organising are all positive attributes in Kneecap, which goes some way toward explaining the heavy emphasis on drug-taking hedonism that runs throughout, a careful counter to the characterisation of moralising busybody do-gooder that in other times and contexts has stuck so well to militant gaeilgeoirí. Indeed, when Irish does occasionally appear in earlier ROCK instalments, it tends to reek of worthiness, a tool for virtue-signalling southerners for whom gaelscoileanna are little more than feeder schools for the elite private institutions.

That there is something important and vital at stake is absolutely clear in Kneecap. The achievement of bringing so many people to see an Irish-language film, both within the island and without, is enormous. The band and the film itself combine masterfully punkish attitudinizing and youth-coolness on the one hand, and mainstream institutional endorsement on the other. The Kneecap thing is slickly done and, with money from TG4, Northern Ireland Screen, Coimisiún na Meán and Screen Ireland, plus public endorsements from people such as Elton John and Cillian Murphy, and positive coverage everywhere from the Guardian to the LA Times, they will bring the Irish language and the reasons why it should be spoken to more eyes and ears than perhaps anyone has ever achieved. They also show no sign of toning down their solidarity with Palestine, which will surely hurt their chances when it comes to the Oscars, now that the film has secured the Irish nomination.

Joyce jokes in A Portrait of the Artist that the best English in the world is to be heard in Lower Drumcondra. Ross O’Carroll Kelly would be dismayed to hear this, given that it is on the northside, but he would also have to admit that he is no judge. In fact, he might not even understand the statement, whether joke or not. Being in judgement about language, having an opinion of any kind, is a sophisticated thing in the ROCK universe. In a way, this is a kind of guarantor that the language that does get spoken there has a kind of spontaneous purity, as it flows with so little friction. In Kneecap, the characters can only dream of being so mindlessly expressive. When we look ahead to the process of unification that is surely underway at this stage, the unionist-nationalist divide will occupy much of our attention, but other, vast cultural gaps run through the island, as the difference between this book and this film illustrates.