The remains of unquestionably the greatest intellect of the nineteenth century, Karl Marx, are buried in Highgate Cemetery in London. I recently tossed a red rose on the site. I doubt whether Judge Gerard Hogan, to whom I have addressed previous articles in this series, or any other legal positivist, would do likewise.

While positivists often engage, though disagree, with rights-based -thinkers such as Ronald Dworkin, most exhibit a level of incomprehension, and often outright hostility towards certain forms of Radical Jurisprudence. No doubt the often unclearly expressed ideas of late Marxism, structuralism and post structuralism often are a factor, but that is only a partial excuse.

Noam Chomsky – himself a linguistic positivist – once made a comment to the same effect on these authors, exempting Michel Foucault. He had developed a rational understanding of Foucault, but none for example of Derrida, who many including myself regard as largely intellectually fraudulent. Indeed, many Cambridge University philosophers objected to the conferring of an honorary degree on him, although I believe there is an element of truth to his babbling on relative truth or foresight.

This plan of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison was drawn by Willey Reveley in 1791.

Panopticon

It is, nonetheless, easy to see why, as far as my harsh assessment of post-structuralism Foucault is exempted. Foucault makes very relevant contributions to Jurisprudence and the practice of law.

First, the transplantation of Jeremy Bentham’s idea of the panopticon – the all-seeing surveillance prison such as Kilmainham in Dublin – is in Foucault’s view a depiction of modern society, where a uniform doctrine is enforced in schools, law courts and hospitals, leading to blind conformity.

Foucault presaged the age of Surveillance Capitalism and 24-hour data surveillance in Ireland, achieved in camera in the Quirke Case through the representations of the Minister for Justice Helen McEntee. Thus, we have a global panopticon wherein the value of privacy and freedom is thrown to the wolves.

Now our judges aside from Hogan, most recently in the Dwyer Case restricting the privacy right, ignore ECHR and EU law. This undermines an ideal of liberty, at least as old as J.S. Mill in modern times, and in fact going back to the Greeks. So, Foucault’s insight is not about postmodernism. It translates into the destruction of rights under Article 3 of the Irish Constitution and 8 and 5 of the Convention.

The second of Foucault’s contribution is his book on madness in the age of reason. The fundamental tenet is that the Enlightenment / Age of Reason involved the necessity, intellectually and then institutionally, to confine the unreasoned – those who were called mad – into asylums. Well, who is mad and who is clinically insane?

The recent US Democrat convention, with the rather wonderful Mr Walz speaking from the heart on middle-class US conservatism about banning books and depriving choice stands against that Twitter conversation between Musk and Trump.

The problem of reason and madness is also clear earlier in Ken Kesey’s masterpieces ‘One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest’ (1962). What happens when the lunatics have taken over the asylum and a dissident voice says no? What of when the man or woman of reason, the pursuer of nuance and grey, the boy who cries wolf, the creature of the Enlightenment is locked up by those who are in fact self-interestedly insane.

Foucault was apparently not on the UCD Jurisprudence syllabus in the late 1970s. A short journey to the Arts block to encounter Richard Kearney’s expertise in Continental Philosophy would have been beneficial.

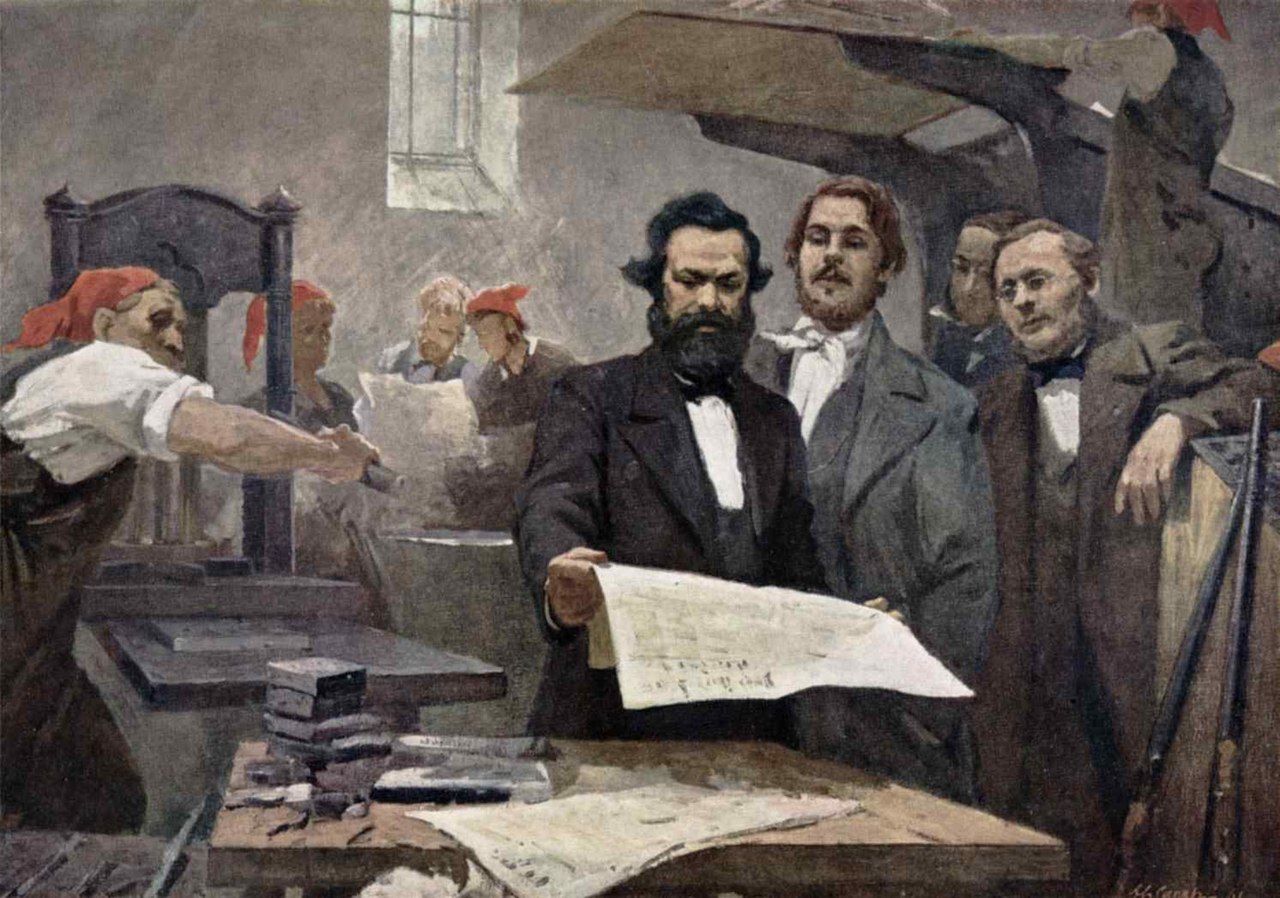

Marx and Engels in the printing house of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung. E. Capiro, 1895.

The Crucial Figures

The crucial figures of radical jurisprudence are not the structuralist, even Foucault, but the great Marxist theoreticians. For Marx law was a mirage, an ideology upholding the interests of the bourgeoisie, He considered it a mere superstructure determined by the economic base. Law, he observed, served the interests of the ruling class.

Thus, in Marxist terms Hogan’s analysis of Kelsen is a form of intellectual masking or ideology justifying a form of state authoritarianism, which Marx would surely have interpreted precisely as the Populism of the petit bourgeoisie. No judicial deferral should be granted to the popular sovereignty of the mob.

Marx though is not consistent about law. He argues that in the properly ordered Communist society there would be no need for laws, as we would spontaneously co-operate in our Communist Nirvana. But at times he concedes, inconsistently, that law is not always bad, and a close textual analysis of his views on property rights, and the freeing up of the alienation of estates to facilitate greater capital, shows that sometimes the superstructure can influence the base, and thus influence economic relations.

So, what of Ireland controlled by a landlord class achieving nothing and facilitating careers going nowhere except to Microsoft and criminal banks, or the legal service class who act like vultures preying on the vulnerable on behalf of the powerful?

The legal realist Oliver Wendell Holmes in his famous rebuke to unregulated free market economics in Lochner (1905) said the Fourth Amendment does not enact Mr Herbert Spencer’s social statics, and nor should the Irish Supreme Court enforce the interests of the commercial fat cats of Aran Square or elsewhere.

Many Marxists, such as Lenin, saw the necessity for rules in a never-ending interregnum on the way to a Communist Utopia, which is never to be achieved. More pragmatically, the fundamental question for any judge which the Marxists pose is: whose interests do the rules serve?

The Marxists influenced the critical legal studies movement, which to some extent educated me, adopting the radical indeterminacy thesis, an idea borrowed at one level from the legal realists. They argue that given the plasticity and malleability of rules, legal outcome can be very unpredictable and in fact subjective.

There really is no such thing as a ‘plain fact’ or literal interpretation of almost any legal text. To avoid nihilism we should invoke moral principle as a corrective.

Alienation

The term alienation coined by Marx more generally to describe exploitation of workers serves as a warning as to how our government is destroying both the working and middle classes,

Subsequent Marxist have been more approving of law. The legendary Antonio Gramsci, while imprisoned by Mussolini, adopted the phrase ‘hegemony’ to suggests as necessary a form of co-operation in law, politics and culture between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Now this coalition argument suggests law can be used as an instrument of social change. That depends on a desire to change for the good.

One wonders whether the new, petite bourgeoisie-aligned Keir Starmer government in the U.K. should be a source of optimism or seen as a false dawn? More taxes on the wealthy, or further savage austerity for the poor?

The Rule of Law is a central concept in jurisprudence, though hotly contested, and Marx aside, it has dominated the thinking of some of the main Marxists thinkers of recent vintage.

In his codicil to Whigs and Hunters (1975), E.P. Thompson expressed a view on the Rule of Law as an unqualified good, which at times could check arbitrary authority. That of course assumes the Rule of Law exists in an ethical polity. It is not that evident in Ireland today as core principles are violated or improperly implemented.

Thus, the independence of the judiciary is not obvious in Ireland, the use of in camera proceedings, akin to the promulgation of secret laws, is a cardinal violation of the notion that justice must be carried out in public. We also find an apparent tolerance of police corruption, the abandonment of substantive rather than formal equality, and indeed the abandonment of constitutional rights.

Thompsons argument is premised on the idea that the judges are willing to enforce the rule of law, often with the effect of unsettling vested interests, as in the recent, painfully prolonged, Assange case. Irish judges are more likely to do the opposite.

Jürgen Habermas

Habermas

Jürgen Habermas is, as ever, a crucial contemporary thinker, and, with all due respect to Gerard Hogan’s veneration of Kelsen, he is not just the world’s leading intellectual figure but the towering German intellect along with Thomas Mann and Kafka of the 20th century.

Since Habermas abandoned the Frankfurt school, and thus post-structuralism, he has become, for over fifty years, one of the great proponents of the Rule of Law and legalism. He stresses the importance for judges not to subvert rights and parliamentary laws protecting civil liberties including the right to protest, viewing civil disobedience as central to revitalizing democracy.

In contrast, the knee jerk reaction in Ireland and the UK has been to give more powers to the police to regulate dissent.

Habermas’ other idea of communicative action, borrowed at one level incidentally from the arch positivist Austin, is the elaboration of the idea of ideal speech. His ideal for the vindication of speech rights is the eighteenth century salon. The ideas of communicative action in legal and judicial terms blends into the ideas audi alterum partem (‘listen to the other side’), and the obligation not to be either subjectively or objectively biased.

Ideology, a term adopted by Marx, has been reinterpreted by Slavoj Žižek, drawing on another Marxist in Lacan, as ideological misidentification. In both instances, and applied to law, there is the sense that the bureaucratic class are engaged in false consciousness or deceptive ideas.

Lon L. Fuller, who is not a Marxist but a natural lawyer, argued that once a legal system has not a tinsel of legality left, but enforces barbarism, it is no longer a legal system.

To round the series off, a Marxist would fully understand the rage of Populism, but not necessarily approve of it. Of course pure Communist societies do not work, but nor does pure neo-liberalism. Indeed, Ireland is not working except for the landlord class.

What does work legally ethically and morally is a social democratic Just Society advocated by the master John Rawls. What does work is Sweden, Denmark, Norway and much of northern Europe, where people are not in Marxist terms commodified and viewed as product, but in the moral Kantian sense things in themselves.

John Rawls intellectually speaking would never have existed but for Karl Marx and a difficult thing for a legal positivist practitioner to realise is that Marx is in fact the greatest of all legal, political and economic philosophers. This is not to say he is entirely correct or a model to be followed in overall societal regulation, but a useful corrective to interpret laws and asses whose interest they serve and, if necessary, to bend rules to achieve socially just outcomes.

Dworkin in fact argued that the South African judges during Apartheid should potentially have lied about the content of a racist law. I also agree or rather at the very least that they should have interpreted it to bring about socially just outcomes.

Marxism at its best focuses on civil and in particular social and economic rights, and the judiciary responsibility to enforce them into the law and the Constitution, to the extent that this is consistent with the Rule of Law.

Feature Image:Tomb of Karl Marx, East Highgate Cemetery, London.