It was one of those frequent blustery evenings, Wednesday May 18th, 2011. I was driving back to Rosses Point from Sligo town. In five minutes one could get soaked, as I had earlier and would after. The wind would blow like hell and clouds give the sky over to shades of light blue and grey as dusk approached. That morning, the water in the tidal channel connecting Sligo Bay to the town was choppy, wind- churned, a kind of deep green. By evening’s light it was calmer, a fuller cerulean than the sky itself.

I had been having a bout of sinus headaches. A great man for the self-diagnosis, here’s how I assessed the possible causes: 1) indoor dampness from the more or less daily Irish rain; 2) drinking too much, not stout or John Power whiskey, rather strong black tea by the gallon; 3) consuming lashings of white flour in the form of croissants and sausage rolls from the bakery run by the French family off Rockwood Parade; 4) a non-fatal overdose of the scones dished up warm with butter by Jill Barber and her crew at the Drumcliffe Tea Shop by the Churchyard where W.B. Yeats is buried. I felt like I was coming down with something.

My friend Martin had waxed lyrical about a Leitrim-born homeopath in Sligo town, Maura. He characterized her as a good listener, a healer. He said she might have something for what ailed me. My batch of Euros was dwindling. That year everything in Ireland was twenty-five percent more expensive when compared to American prices, yet I was curious enough to see could she help the sinus ache or maybe persuade a high-pitched constant companion – screeching in my ears – to abate. More than that, I thought I’d get an appointment because frequently my default mode could be characterized as uptight, on alert – shoulders up, jaw clenched, muscles clamped down, my head mimicking a fist. The resultant drag on my energy wore me down.

I had a 6 p.m. appointment with Maura. Inevitably, I got caught again in a blast of horizontal Northwest rain during the short walk from the Tesco’s parking lot in the centre of town around the corner to the faded elegance of the office buildings at the West end of Wine Street. A British legacy, eight three-story grey Georgian houses were built in a terrace in the 1830’s with large square windows, decorative semi- circular glass above thick wooden front doors and terra cotta pots atop concrete chimneys. They still look decent despite pipes running down the front of several to drain rainwater off the slate roofs.

Imbibing Sligo Life

Born a stones-throw away in Garden Hill Nursing Home, I had imbibed life in Sligo as a toddler. Gripping my father’s trouser leg, I observed the goings on around him. I would scamper after him into Blackwood’s General Store on Grattan Street, a place of creaky wooden floorboards sprinkled with sawdust, populated by white-coated shop assistants. After forking out for a pound of rashers, my father would point to the cylinders flying about the ceiling on wires. The shop assistant wrote up a slip and put it along with cash into a cylinder, pulling a handle to send it flying up to a mezzanine office that appeared to be suspended from the ceiling. From that vantage point a bespectacled old dear made up the change and zipped the cylinder back down. Once or twice every summer, my father bundled me into the front seat of his black Ford Consul and drove me down Cartron Hill into Wine Street to the Café Cairo, its floor tiled in black and white squares, for a whipped ice cream cone.

The world of my early boyhood was circumscribed by the wider landscapes of Sligo – limestone encrusted Ben Bulben, the fresh waters of Lough Gill and the Garravogue river running through town past Foley’s Brewery to the weir at Hyde bridge where we tossed lumps of sliced pan to the swans. Along the coastline, I ran after my father to keep up on his walks in the salted air off the Atlantic coast: Raghley, Strandhill, Rosses Point, Mullaghmore. Running in place against the wind, knees reddened by the chill, brown long socks pulled up tight in wellie-boots I watched my father, his shoulders thrown back, stride away from me into the ghostly distance of the mist enshrouded second strand at Rosses Point.

I stepped through the glass front door of number two Wine Street through the vestibule into an office to the right. In the old days, doctors had offices along this part of Wine Street. Maura’s place was a new twist – a gang of alternative practitioners sharing space, naming it the Wine Street Wellness Center. Maura arrived in and walked me up the U-shaped staircase to the first landing. To the left, her high-ceilinged office looked shared – no visible personal items or files – and the furniture was second-hand. I sat in a low uncomfortable chair with my back to the door while my soaking raincoat dripped across the only spare chair. I viewed Maura in profile at her bare desk facing the wall.

She asked me all kinds of questions, about my aching back, ringing ears and all of the things happening in my body certainly but also in my emotional world. She had a series of gently probing questions. As I blabbed replies, she seemed to let my story wash over her, writing the odd clue she extracted down on a notepad. She asked how did I feel about this or that time in my life, all with a view to “restoring the body’s natural balance,” said she.

Balance, as far as I was concerned, was something others might attain not me. I had been keeping my eye out for balance of some sort for years – balance between my tired body and racing mind; between work and play; between pushing myself to forge forward and sitting back to rest. I wasn’t sure what balance felt like.

Massive Turning

Prompted by her expansive questions, my mind’s eye drifted to a massive turning in my life – February 1989. My mother, Mella, took ill suddenly, fatally. I talked to her on the phone the day of the hastily scheduled surgery – open heart – and she said, “Don’t come now; bring the kids in a couple of months, it will be just the tonic I need.” She called my toddler sons her little darlings. Barely twelve hours later, a loud phone bolted me awake in the early hours – the call every emigrant dreads. My elder brother Vivian killed me softly, “She’s in a bad way; come home as quick as you can.”

Sitting there in the thrift store low chair, I told Maura I was remembering the agonizing wintertime plane trek home to Ireland. Every minute of the journey from Pittsburgh to JFK in New York to London Gatwick and on to Dublin was drawn out, excruciating. “Six hundred miles an hour, bollox,” I remember thinking somewhere over the Atlantic as the steward poured another weak tea into my flimsy plastic cup. At Gatwick, extra security checks delayed me further. With the IRA active, all Irish travelers were suspect.

Years before, just passed my twenty-sixth birthday, when my eldest brother Ian phoned to tell me my father had died of a heart attack at the age of seventy-two, I knew by the tone of his, “Hello,” what was coming. When he said, “I’m afraid I have bad news,” that sealed it. His news was not entirely unexpected. My father had drifted downhill after retiring at the age of sixty-seven. This call, though, this one struck like the once in a lifetime tornado that had ripped up parts of Pittsburgh, my adopted hometown, in 1980. Out of the blue, Mella, ten days before her 70th birthday, was lying in a hospital bed in Dublin close to death; nothing I could do would speed me to her side. Stuck in mid-air over mid Atlantic, I resorted to talking silently to her.

“I’m coming. Hold on, dear one, hold on.”

Vivian awaited at Dublin airport. He shepherded me to his green Mercedes with the tan leather seats. In silence, my brother the motor racing champion sped me through the early morning fog like a VIP, across the semicircle of Dublin Bay anchored by the chimneys of the Bull Wall, past the strand at Sandymount where people braved the early morning wind and drizzle to walk dogs. Ignoring speed limits, he revved the purring engine as we waited at the railway crossing for a DART commuter train to rumble and clatter past. The back end of the Merc fish- tailed as he turned left with a screech onto busy Merrion Road – bobbing and weaving in and out of clogged traffic lanes – straight to the Blackrock Clinic.

A Preternatural Tristesse

“What are you feeling now?” Maura asked. “Sad,” I told her.

Sad wasn’t the half of it. A preternatural tristesse had descended on me, as if I was touching an opening, a small portal atop an immense reservoir of sadness, a deep subterranean lake of tears like an underground aquifer. I was surprised, nonplussed, to discover it. The grey twilight threw shadows scything at an angle across the top of the wall and along the corner of the high-ceilinged room.

“Right,” she replied with an inflection that combined, “I hear you,” with “I accept your story.”

Slumped slightly in the non-ergonomic chair, I felt my shoulders relax a little, involuntarily let go of a layer of tightness clamping them down. There’s not enough time in one lifespan, I thought, to cry all of those tears. I sat there wondering if I had somehow not dealt with buried grief around the loss of my mother, whether words unspoken – words of love and affection, respect and gratitude – were still stuck in my gullet after all these years, or whether part of that lake of tears might even belong to her and my father or ancestors, not be mine at all.

As Maura consulted a large reference book, I remembered that my father and the gregarious Denis Boland regularly sipped John Powers in the second floor living room of the Boland’s Wine Street house a couple of doors along, the one with the plaque outside that stated simply Surgeon Boland.

They drank pints in the Yeats Country Hotel in Rosses Point with the town’s elite, Tommy Mulligan of Western Wholesale Company, Jimmy Doherty the Accountant, Toher the Chemist who drove a Volkswagen Beetle, Armstrong the Solicitor, the businessman Soden and cigar smoking wit Doctor Charles McCarthy.

My mother too enjoyed friendships in these houses along Wine Street with May Quinn, the dentist’s wife, and big-hearted Moya Boland who held court from her kitchen, always at the ready to entertain visitors who wandered in off the street. May Quinn’s early death from cancer rattled my mother. They were like sisters the two of them – good looking, blond and wispy with tan makeup. Golf buddies at the links in Rosses Point, after playing a round they giggled together over gins and tonics in the member’s lounge.

“What we are looking for,” Maura said, “is a constitutional remedy; one that gets underneath surface symptoms to draw out the body’s own capacity to heal – physically and emotionally.”

First Train Trip

Memories were overtaking me. I didn’t tell her that earlier that day a walk to the train station at the West end of town had caused me to re-live my first trip in a train – from Sligo to Dublin with my father and younger sister Adrienne. I was six or seven. Oblivious to what packing up must have been going on, I thought we were on some sort of adventure to see Dublin, a dream-place I could not conceive of.

I quizzed my father at each stop. “Where are we now?” Longford, Edgworthstown, Mullingar, Kinegad. The train stopped along the way while in the hushed carriage people shuffled on and off puncturing the quiet by banging the thick green doors shut then dragging bags along the light brown linoleum floor before heaving them onto overhead racks.

On the outskirts of Dublin approaching the city centre the train slid by small brick-walled back gardens. The train tracks were high. I could see over the back walls into tiny yards where between light rain showers daily washing blew on lines. In some places there were narrow laneways between the back walls and the railway. Elsewhere, smashed up bicycles, beat up chairs and prams, Walkers brand with metal springs sticking out, lay rusting beside the tracks. Approaching Westland Row station, small windows with white lace curtains hid tiny darkened bedrooms from the train.

Somehow, we landed up in 72 Cowper Road, a tall elegant Victorian with stained glass on the front door, a half block down from busy Rathmines Road. Welcomed in by my maternal grandparents, I followed the adults like a duckling to the kitchen at the back of the house, down a couple of narrow steps behind a door with curtained glass. My mother and two elder brothers had arrived by car; suitcases had been unpacked. How did these ancient, quiet people – gentle souls – Joseph and Margaret Hynes, cope with six of us landing in on top of them, sharing beds, sleepily whizzing into piss-pots in the middle of the night? Even then I wondered.

We Weren’t Going Home

As one day rolled into another it dawned on me gradually, we weren’t going home to Sligo. We were enrolled in schools. We had moved to Dublin for good. I walked to Miss Carr’s elementary prep school on Highfield Road, my brothers to the bottom of Cowper Road and over the railway footbridge to the Jesuits at Gonzaga College in Ranelagh.

After a couple of months of this routine, we moved to a new house nearby in the quiet leafy confines of Merton Road, number 42. I recall no explanation at the time, or at least none that I could comprehend. As an adult I inferred there was sacrifice involved for my parents. They moved us from Sligo, where years on my mother would confide they had enjoyed their happiest times, for a fresh start – to be closer to aging parents, enroll us in top schools and expand the family to five children with the Dublin birth of my brother Colman.

I was an hour in the chair answering questions, pausing for Maura to make notes or look something up, when she declared she had an idea for a remedy for me but wished to think about it further – I could stop by for it in a couple of days. A gust of wind shook the windows just as she opened the office door to graciously escort me downstairs to the front door.

Steering left out of the Tesco’s lot, I drove West along Wine Street, then turned right on the Inner Relief Road, the new bypass that cuts off the West End of Sligo from its center. Past Hughes bridge where the Garravogue joins the tide, I veered left off Markievicz Road up Cartron Hill past my boyhood home, called Inniscara this longtime, down the other side, across the causeway and out the Rosses Point Road.

I found myself teary-eyed approaching the village at the neo-Gothic limestone Protestant Church on the left marking the widening onto the “new” promenade road built in the 1970’s, the one that “desthroyed” the village, according to two locals, semi-permanent fixtures on the bar stools of Austie’s Pub. Uachterán na hÉireann, President of Ireland Mary McAleese was coming over the car radio on RTÉ addressing a state dinner for Queen Elizabeth 2nd – Head of State, Head of the Commonwealth, Supreme Governor of the Church of England, top mega-wealthy Royal personage reigning over millions of subjects – Eílis a Dó as they were calling her on the News in Irish.

The last British monarch to visit Ireland had been Elizabeth’s grandfather George the Fifth, who landed in 1911 in Kingstown Harbor, we know today as Dún Laoghaire, to receive the muted admiration of his Irish subjects. At that time Ireland was a colony agitating for home rule, a modest form of self-governance within the Union with Britain.

“What do you think of Eílis a Dó?” a woman juggling a quart of milk, car keys and an Irish Independent newspaper in the village shop in Rosses Point had asked me that morning, pointing to a front page picture of her nibs dripping with royal jewels? “Isn’t she great all the same, for a woman of 85, and yer man is gone 90?”- yer man being His Royal Highness The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, longtime sidekick to Eilís a Dó.

Mary McAleese acknowledged centuries of conflict between Britain and Ireland while asserting those days were well behind us. The whole island, besotted with English football, Downton Abbey and royal weddings, had achieved normal relations with England untainted by mutual threats of violence.

“The past,” said she, “No longer threatens to overwhelm our present or our future.”

A few drops of tears were making thin tracks along my face. Eílis a Dó got up and brought the house down with her opening words in Irish: “A Uachtaráin,” she intoned inserting a barely perceptible pause for dramatic effect, “Agas a cháirde,” President and friends.

“Fair play to her,” our friend Myra Curley, a genial elder in Rosses Point village would declare the following day. Myra followed the royal goings on closely.

Oyster Island

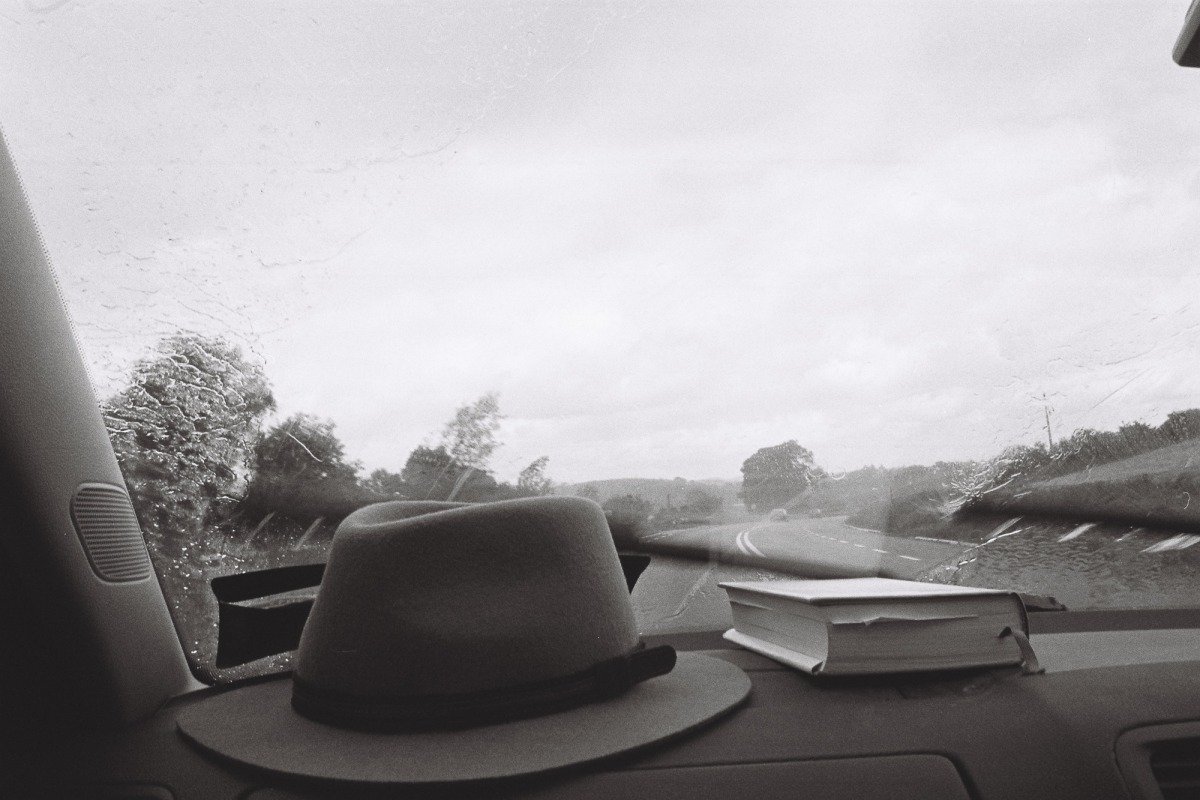

The better to listen, I pulled the car over on the promenade road a stone’s throw from where Oyster Island lies across a narrow tidal channel. Evening wind blew low hanging grey-stained clouds across the sky. Gazing over the undulating tidal waters, it occurred to me it was my lot to be removed at an early age, exposed the way maybe gannets or terns off the coastal headland at Mullaghmore, twenty-eight kilometers North of where I was parked, are battered by the elements.

Migrating birds return again and again to their origins, over and back, over and back, tracing and retracing infinite invisible patterns on the air. For four decades, I have mimicked their returns.

Since leaving Ireland at the age of twenty-three I came back every chance I got, always returning to Sligo, never feeling fully American yet I was cut off from the day-to-day routines and interactions that would render me an Irish local once again. Toward the end of every trip before returning to Pennsylvania I pined, the way a long-distance lover’s heart cracks a little at the prospect of further separation from a beloved.

Here I was again, rummaging around the landscapes and buildings of my early boyhood, a familiar desiderium setting in. My mind drifted like a cloud to the year of my father’s death, 1979. In quiet Mullaghmore on the morning of August 27th, the IRA blew Earl Mountbatten of Burma to bits in his small fishing boat, Shadow V. Three others were killed too when the creaky boat exploded beyond the long sandy beach where the harbor opens to Donegal Bay. Among the dead were Mountbatten’s fourteen-year-old grandson Nicholas Knatchbull, whose twin brother Timothy survived, and Paul Maxwell a fifteen-year- old summer helper from Northern Ireland. Prince Philip, Mountbatten’s nephew, stood silently and stoically with the Prince of Wales as the coffin draped in the Union Jack arrived back in England. Surgeon Boland of Wine Street had treated survivors at Sligo General Hospital.

Years later Paul Maxwell’s courageous father, John, somehow found it in his heart to publicly support the release under the Good Friday agreement of one of the perpetrators, Thomas McMahon of Carickmacross, after nineteen years in prison. McMahon would refuse requests to meet with John Maxwell, who wanted to see as he put it, “Would he be capable of putting himself in my shoes?”

The Good Friday agreement having settled more or less the Troubles in Northern Ireland, rendered possible the Royal visit and the elegant speeches coming over the car radio. It occurred to me that seeds of sadness in me, the trickle of tears on my face, may have their origins in grief and loss engendered by leaving Sligo as a small boy, Ireland itself as a young man.

In the late seventies, there was nothing much in the way of opportunity for young people. For most of the eighties Ireland exported a hundred thousand young people annually – a diaspora largely forgotten and wholly ignored in the country’s public discourse. Idealism and romance were calling my name and I chose to flee to the States with my American beloved.

It took several years to break upon me what had happened. I had removed myself from places, landscapes, language, people, culture and the very air I took for granted breathing. The poet Eavan Boland put it this way, “An ordinary displacement, had made an extraordinary distance between the word place and the word mine.”

To be sure, my migrant’s longing was no match for loss and grief suffered by Paul Maxwell’s family and the families of those killed and maimed by the troubles in the North. Sitting there in the car, I felt grateful for the magnitude of John Maxwell’s compassion, inspired to follow his example – to deploy further measures of compassion toward my uprooted younger self.

A few days later I would take a small sugary pellet, the remedy Maura doled out, and feel a further calm descend. The sinus problem would abate a bit.

Beyond the chilly tidal channel, clouds cast a shadow across Knocknarea. Evening light played hide and seek with the burial cairn of Maeve, ancient Queen of Connacht, atop the mountain. As teardrops dried on my cheekbones, Elizabeth Regina declared, “We should bow to the past, but not be bound by it.” I felt my neck muscles relax further as a soft rain peppered the windshield.

All Images (c) Daniele Idini