Does an age of frenetic online activity afford time for literary masterpieces, especially Outsider Novels, transcending what is considered ‘normal’?

He whose vision cannot cover

History’s three thousand years

Must in outer darkness hover

Live within the day’s frontiers.

The above stanza is from a twelve-book, poetry collection by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, which was inspired by the work of fourteen century, Persian poet, Hafez.

Rather than take the above stanza as concrete, it is worth taking it as an allegorical device, and metaphor, for what this piece sets out to champion: the work of the literary Outsider.

With various electronic devices such as, the laptop, smartphone, iPad, and media outlets like Netflix, YouTube and other broadcasters, vying for our attention(s) – and successfully so – one must enquire into whether serious, attentive reading means anything anymore?

Has the modern age – the tempered, electronic milieu – filtered out literary tomes?

The very idea of ‘The Outsider’ literary work may be unnerving in what is an age of tantamount addiction to a frenetic social media; what the writer Will Self refers to as ‘bidirectional media.’ The resulting anxiety disinclines us to engage with what many may deem ‘difficult’ books, or ‘heavy’ tomes. Knocking the bottom out of the known literary universe.

It might be said in relation to reading such books: who has aeons of uninterrupted time? In response you might say that the pandemic and lockdowns have afforded us such time. Note: no banana breads were harmed in the writing of this piece.

Critics sometimes venture towards difficult literary works from a canon such as that identified in Harold Bloom’s tautological, yet, feverish and impassioned, The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. These are the works of literature which ebb in from the external to the field of the Literary Arts, and which Bloom eulogises in his reviews.

In 1812 by the Russian artist Illarion Pryanishnikov.

War and Peace

Who has read Tolstoy’s big bangers? War and Peace anyone? History’s frontiers fought over during the Napoleonic Wars, backed up with sweeping pastoral symphonies; with a charge of Russian calvary sweeping through the narrative, backed with Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. A silver Samovar dispensing tea in the officers’ mess, the colour of unearthed rubies; tea sweetened with a cube of sugar, held between the drinker’s teeth.

Or Tolstoy’s more subdued asides, with bucolic scenes of bleating lambs; and navvies sitting down in a wooded glade to consume their lunches. While out there in high summer, in the protracted Russian steppe, brown bears nosey along through tall grass to hallowed fishing grounds. With a scurry of gnats flitting at their ears.

Or what about Joycean punnery – the nightbabble of Finnegans Wake – or Beckettian gurglespeak?

If the safe, go-to novel is a halfway-house where thoughts run easily along the neuron-led rafters; where sable-eared bats hang, unruffled, in the belfry; where a forgotten greenhouse with cracked panes of burping green glass dwells in the back garden of the mind, they are there serving as a concrete, model village. Known territories; safe catch-all neighbourhoods, which imbue the reading-self with tangibility.

There has been a loss of faith in big difficult books due to less than attentive mindsets; and upon latching on this, Mediocrity Inc., sweeps in to garner easier-to-read works, which dominate book charts. What does this say about the demographics so enamoured by ease of access?

Literary, like most paradoxes, operate through conflating, and contracting, obligations. They are in a constant state of flux. (Not helpful for the binary-seeking world of the definite article, which Mediocrity Inc., often seek out to nail to the masthead.)

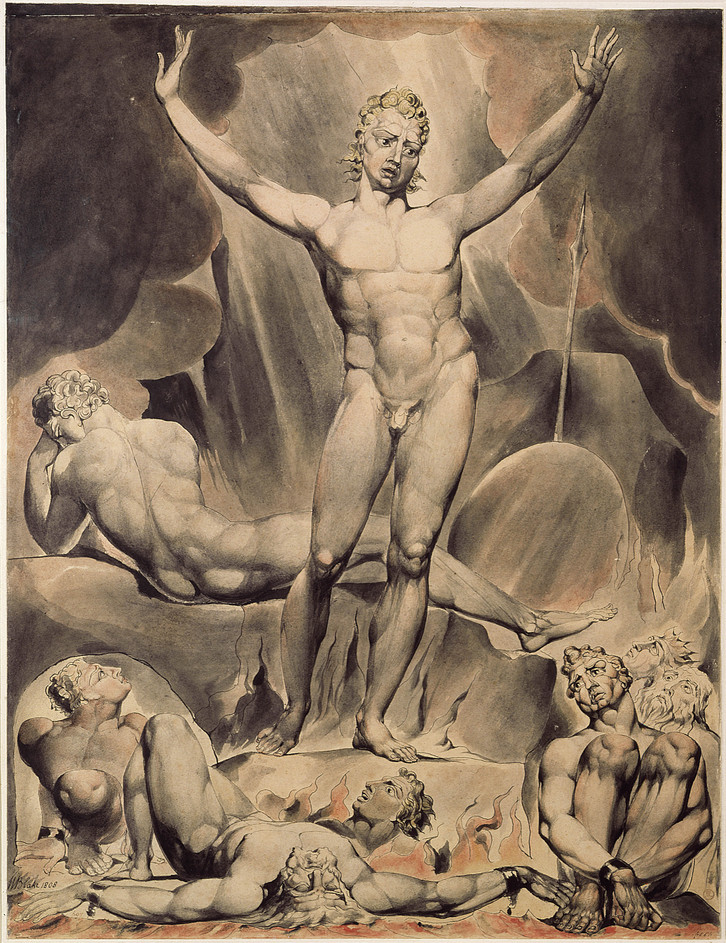

Satan Arousing the Rebel Angels, William Blake (1808)

Self-Made

When all the joy of writing is being sucked out of it by marketing mentalities, then things are in a bad way; they are, rather, Miltonesque: bleak; morally obtuse. Greed has taken over the minds of formerly, we hope, reasonable people.

Quality dissipates in such trends.

If you put your faith in the superficial, then the meaning of actual literature – that with substance – is diluted. Worship at the golden calf and you cannot expect your palpating thirst to be quenched.

However, the brave, writing for themselves, writer(s) will always venture out towards a different plane to help buck these acclamatory, accepted trends. The strongly composed novel could be summed up as a transference of the quotidian whereby one’s will becomes the whole of the fictional law in an expansive, infinite world.

Will Self is such a writer whose output is ‘challenging’. A writer, thinker, who goes it alone and does not yield to the Mediocrity Inc., whose plaintive, rebellious, immature cries rail that they know better, but which do not.

Outsider Novel

The stolid mentalities who often quip, “I couldn’t get into it”, say this, because, I believe, they are not prepared to challenge their perceptions of what the Outsider Novel means to them – an ungraspable leviathan which slips away into the listless fog.

Five or six literary Outsider ‘heavy’ novels from the Western Literary Canon dominate and stand on the rostrum; representing the cornerstones of the literary house that encapsulate the Canon.

Two have already been alluded to, and then there is: Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy, Gentleman. Bellicose in its exposition from conception to the screaming infant through to his uncle’s nose and to maturity.

One of the first ‘Outsider’ works, it is inspired by the Rabelaisian, and inhabits the world of the absurd and the fabulist. There are long paragraphs on his Uncle’s Toby’s European adventures with his servant, Trim, and of course, reams of information on the prowess of his conk. It will have you amused if not bewildered at the thought of how he got away with publishing it in the 18th century.

James Joyce’s Ulysses is a tome in tribute to the mimesis of life, and everything which Joyce termed ‘A shout in the street.’ It takes the epic towards modernism, and a rebirth of consciousness in the early-to-mid twentieth century. There are diegetic elements to the inner monologues of the characters and the streets of Dublin. You will find an urban mammoth with its quarry caught upon its wide tusks, braced with metal struts to keep the weight of the tome from falling.

This is no Cuneiform script to procrastinate over, it is a layered, complex novel to be discovered. Through two main characters, Leopold Bloom, and Stephen Dedalus we find an unparalleled commentary on twenty-four-hours in Dublin on June 16th, 1904. That is the plot. Simple. Yet, all-encompassing. Tributaries, feeding into the literary infinity pools of the Liffey, and further afield.

Hopefully readings of Ulysses will soon resume in Sweny’s Pharmacy.

Neil Burns takes issue with the 'artsy sentimentality' of those objecting to James Joyce's 'Dead House' on Usher's Island being converted into a hostel.https://t.co/d3HPHAckUe@Andrea_Rey48 @FintanOHiggins @CSBlenner @broadsheet_ie @CllrEoinOBroin @wadeinthewate11 @IlsaCarter1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 6, 2020

Gravity’s Rainbow and Infinite Jest

Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow is thronged – absolutely imbued – with a myriad of characters, and a talking lightbulb. Each copy of Gravity’s Rainbow should include its own Philharmonic Orchestra to play alongside the running-hare-prose. It is about the Second World War and V Rockets and their trajectory before falling to Earth on the places where a main character is having coitus.

Sounds mad, right? Yes. Quite, but fantastical and industrious. The prow of this literary Gridiron, in a reading, a universal, Manhattan bearing down on the sugary pap and mulch which is dished out – and is not at all, nourishing.

Launch of a V-2 rocket.

David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest is totemic in its appreciation of Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, with a nod to Don DeLillo, and John Dos Passos’s U.S.A trilogy, mainly, The 42nd Parallel.

The plot of Infinite Jest is initially tertiary to Wallace’s intellect and ego in fluidity. The beginning is pure vaudeville to the main circus, big-top act which is the intellect of Foster Wallace himself and the prefrontal cortex mythology, which he conspired to create and then exuded, seemingly, so effortlessly. But did Foster Wallace write a capable work? Yes he did, but it is an apostrophic set of hymnals on tennis, drug addiction and geo-political set-ups.

I looped the meta-modernist, hyper-realist circle and went along for the ride on David Foster Wallace’s encyclopaedic, metadata novel; figuring that while sedate prose is at the behest of book seller’s, and publishers – means and modes of production for the masses – I thought ‘To hell with this, give me a novel with shtick.’

So, by means of reposed epidural, I plugged into Foster Wallace’s acicular vein, man, and plunged the diviner right on into the other side. And it is shtick all the way.

Foster Wallace’s reliance on using nomenclature, acronyms are, well, trifling when you forget all the organisations he coins; we do know, for example, that O.N.A.N stands for Organization of North American Nations, a kind of dystopian superstate which is comprised of Mexico, the United States and Canada, and that the novel takes place during ‘The Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment’ Y.D.A.U. It opens with tennis. Wallace was a court man, he liked to court tennis and he schlongs his racket into being more often than enough in this work.

This is not a linear prose tale as we know it.

Transcendental Idealism

These literary works fail to fall into the crushing jaws of a Western, ‘easy’ read sunset; they transcend the ‘normal’.

The oddity of the largess of such peripatetic works are still revered by committed readers. Literature, and indeed, great literature was, and is, and will forever be, a magical portal which has the power to transport consciousness into another realm. Some works, some bigger, well-crafted works exist outside the normally accepted coda of what is regarded as ‘the novel,’ and do so by existing beyond the ‘day’s frontiers’, beyond paragraphs, in marginalia.

And out there beyond the environs of ‘known-knowns’ lies the quotidian, infinite in its readiness to bypass the grassy verges of rhetoric, and up beyond ionosphere and stratosphere.

On the y-axis of a line-graph in the evolutionary trajectory of the Outsider Novel, one could hope for, works which operate outside the perceived, ‘normative’ structures of the known, easy to digest novel. In a sense they occupy the strata of the strange, the unfamiliar; their tentacles reach into the dark nooks and cervices of the mind and bring lax grey-matter in there forward, and into pulsating, roving life.

Kant’s house in Königsberg (now Kaliningrad).

If one postulates further, and looks at Kant’s Transcendental Idealism in The Critique of Pure Reason, it can be said that space and time are merely formal features of how we perceive objects; not things in themselves, existing independently of ourselves, or properties or relations among them.

Objects in space and time are said to be ‘appearances’, and Kant argues that we know nothing of substance about the things in themselves, of which they are appearances. He calls this doctrine (or set of doctrines) ‘transcendental idealism.’

Ignorance along the lines of myopic conjecture about a novel one has not read, is the syphilitic chancre on the body of literature – based on appearances and perceived conjecture on what a novel is, without taking the trouble to read it. This is harmful, detracting from the creativity behind such a work.

After mooching around town Lev finds a hostelry with a dizzying array of rules. Kafka’s Café is new fiction set in Dublin by Neil Burns evocative of our times.https://t.co/nfaTgp1OGV@foreverantrim @broadsheet_ie @wadeinthewate11 @IlsaCarter1 @Andrea_Rey48 @ggrace1984 #fiction

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) February 19, 2021

Literary Keys

There are literary keys available to break those harder to ‘crack’ literary tomes. Those keys are in other books; yes, books which help you with books. Isn’t that what a dictionary is for, or a thesaurus for that matter?

Take, again, Finnegans Wake, the indolent reader’s worst nightmare – they start by gambolling around in search of the missing apostrophe ignoring the entrée; and hell, they proclaim it to be the most difficult of books.

In Christopher Marlowe’s adaptation on the stories of Faust, Doctor Faustus says, ‘Hell is just a frame of mind.’ The demonic Mephistopheles in Doctor Faustus does, however, imply a similar idea by saying that losing his place in heaven gives him experience of hell wherever he is:

Why this is hell, nor am I out of it.

Think’st thou that I who saw the face of God,

And tasted the eternal joys of Heaven,

Am not tormented with ten thousand hells,

In being depriv’d of everlasting bliss?

If one was to take the evolution of the novel, we could look at Sterne, Joyce then David Foster Wallace and who knows where the creative literary genre will head next?

To Ducks, Newburyport by Lucy Ellmann?

Maybe the form has hit its parabolic arc, and now needs to descend for a while from its illustrious meridian.

Break the mould – escape the insular, self-created Hell and free yourself. Read as far and as wide as the splendid sun, and beyond.

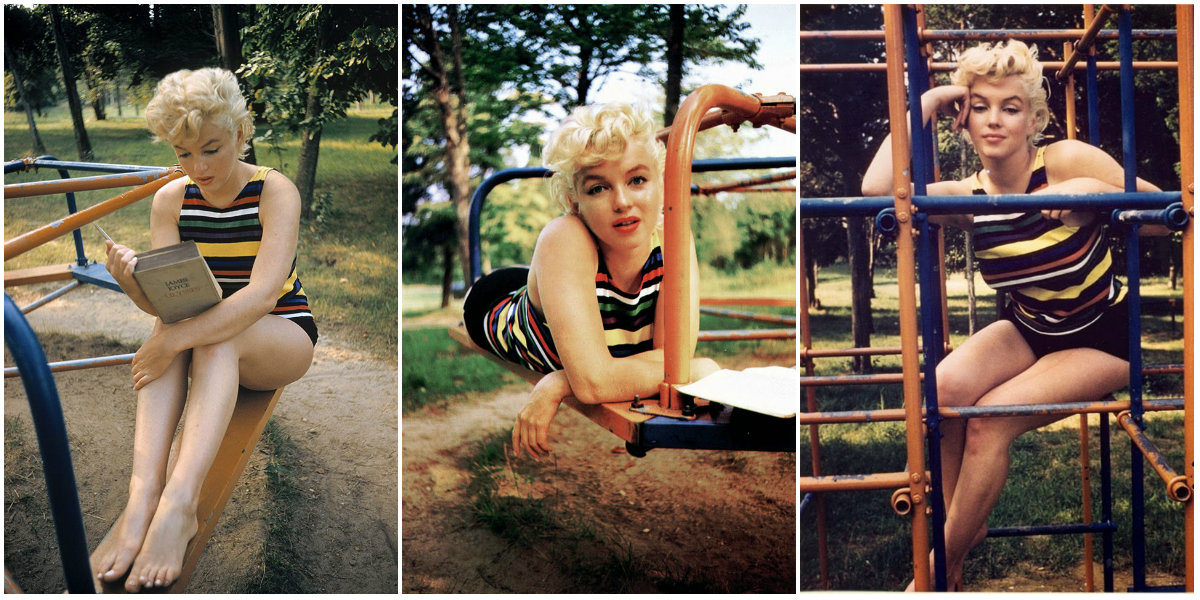

Feature Image: Marilyn Monroe reading Joyce’s Ulysses in 1955 by Eve Arnold.