Whenever I think about Literature I think about Love. Both are written with big Ls. The Elles. Like an enjambment of run on legs, going on ad infinitum.

And when I think of Love I think also, inevitably, of betrayal. One cannot be without the other; the two legs upon which humanity stands. Only in their resolution can we find peace. So, Literature – like His story – is very personal. Let me tell you my own.

It is a story about numbers, mainly Thee and Four. Here I am borrowing from Joyce and Beckett, both of whom in their turn drew from Giambattista Vico, the Neapolitan philosopher, a genius unjustly ignored in his lifetime. Even today, if you ask an educated people about Gimbattista Vico chances are most won’t know anything beyond his Three Ages of Man theory that helped Joyce formulate the structure of Finnegans Wake.

Now let me go back to the women in my life. There were three, you see. I said that this was a story about the numbers Three and Four, but in order to tell this story, I first need to tell you about these three women.

It is a story about Power; all history concerns Power after all.

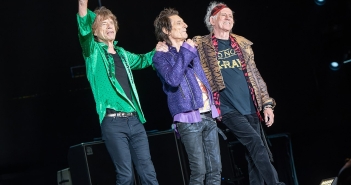

With the first I was in a situation of Power. I could do anything. Or so it seemed. She clung to me. She lay at my feet and looked up to me like I was a God. And I was too. For when you are so very young, you feel God-like. Such is youth!

Look at them now, the youth of today, walking on the street! Love for them is the eternally INFINITE. That is why with youth there is still hope. As they are believers in the truth. It spreads out before them in space and time. Boundless. They are perpetually in a mindset ready for exploration. Of all kinds. This is why some of them love Art and Literature.

Rogelio de Egusquiza‘s Tristan and Isolt (Death) (1910).

Life Moves On

I am in my fifties now. I no longer believe in infinity. For me things are all too FINITE. Where I once saw open space, I now see enclosure.

She used to lie at my feet like I was a God. It’s a great feeling, isn’t it, to have that power! You stand above them like a God or a Goddess, looking down upon them, deciding on their fate.

And of course – as we all know – with such power comes enormous responsibility. The only problem is that when you are young you rarely feel like being responsible. Then one day you decide to do a terrible thing. Everyone does it, at some point. You kill them!

Metaphorically, at least. But this is the first real taste of death, and it is a truly terrible thing. Now, you have the taste of death upon your tongue. The one that you used to kiss. Now, s/he only tastes of poison.

You move on.

It is that simple. It’s called survival. Call this the first age when everything was divine and when you discovered metaphor and the apocalypse of dying.

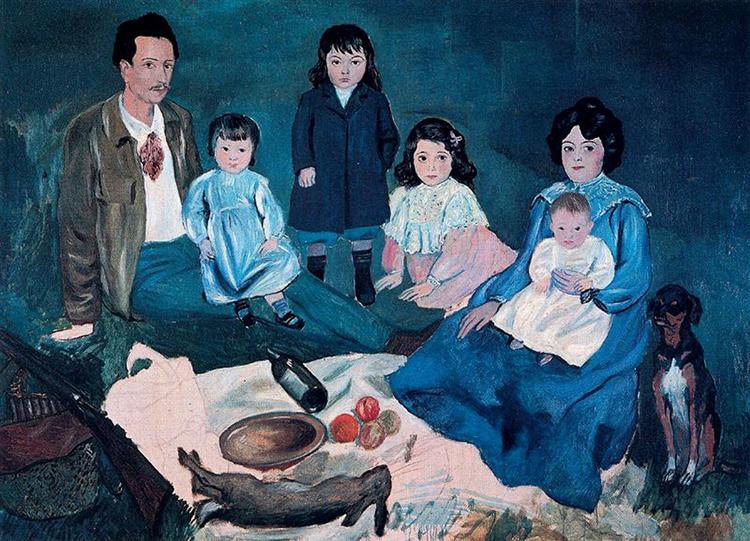

The Soler Family, Pablo Picasso, 1903.

Nemesis and Trinity

So, time passes. You meet another one. Number Two. S/he is your Nemesis. For she will destroy you. Just like you destroyed number One, now your time too will come. Somehow this enters into our conception of justice. What goes round comes round. Karma.

Just as you had looked down, all those years ago, on your first lover; just as you looked down on the one who crawled around at your feet, now you are in that very same position! Who would have thought it? There now, look at you! That miserable specimen down on both your hands and knees before Her, who is looking down upon you. Like she’s contemplating an insect. And, of course, She eventually squashes you under Her boot heels. She crushes and grinds you into the earth so that there is no longer any trace of you. You are extinguished. Finally. You are dead.

There now. That is the story of numbers One and Two.

What happens next? And what, by the way, does any of this have to do with Messrs Beckett and Joyce? Everything, my dears. Just wait. Be patient, as I will explain. I will take you by the hand and help you to join up all the dots.

But first, let me introduce you to number Thee.

Isn’t she a beauty? Now, remember the score is one-all now. Even Stephens, as we say. You are finally at the age of equality. It happens early on for some; for others later on. And for some poor buggers, it never even comes!

You have to will it. But if s/he does come, you will finally have a chance to redeem yourself. For, like her, you too have been broken. You are no longer the youth you once were. Infinity has been clouded by impossible violence. You need to thread carefully now, and hold onto what you have with more caution.

And you do. Whereas before your relationships – that is with numbers One and Two – may have lasted only five or so years, with number Three it is all-enduring. Before you know it, twenty years have passed and you have children growing up around you; who you now cherish as you once cherished your own life.

This is the story of Three. The Trinity, if you will.

Illustration by Malina/Artsyfartsy.

How It Is

Moving on to Samuel Beckett and a story from his How It Is (1961) that has obsessed me like no other in Literature. This novel by the Irish Modernist writer has obsessed me throughout most of my adult life. It acts like a portal into human history through Literature, travelling back to the Ancients of Greece, and Rome. But before exploring this, I must first tell you about Giambattista Vico.

When talking about Giambattista Vico and Samuel Beckett, we must also consider James Joyce. The number three is there again! They form a triad. A holy Trinity. It was Joyce, after all, who asked the young Beckett to write an article about Work in Progress – the working title for Finnegans Wake (1939) – when they first met in Paris in 1928.

This was when he wrote his famous essay Dante…Bruno.Vico..Joyce (1929), in which he singles out Vico – more than the other Italians mentioned in the title – for particular attention, and the important influence of this Neapolitan thinker on James Joyce, in particular on the structural composition of Finnegans Wake.

But it also demonstrated Vico’s influence on Samuel Beckett, a point that has tended to be ignored by Beckett scholars.

Let us consider the essence of Vico’s ideas on the Three Ages of Man, and how Joyce was to incorporate Vico’s theories on history into his epic final novel.

In the La Scienza nouva or A New Science (1725), Vico attempts to break history down into a cyclical process, as natural as the four seasons. In fact, Vico’s Three Ages of Man idea actually contains four parts, and in this Joyce is a stickler. For this reason, though not alone, that Finnegans Wake is made up of four books. One being for each Age.

The Muses Melpomene, Erato, and Polyhymnia, by Eustache Le Sueur, c. 1652–1655.

The Four Ages

What then are these Four Ages? The First is called the Divine Age and language in particular, but also laws, are divinely thought of, or God-given. God in this case is Jupiter, as we are in the Pagan era.

Though, coming from a Christian era, we should recognise the intermediary nature of the Muse Uranus, mother of all the Muses, assigned the role of intermediary between God and man. However, She, in turn, needs a human vessel in order to transfer her God-given knowledge, and this, according to Vico, is where the poets come in.

As it was a theological age, so all poets were theological, unlike today. That is to say, they were only concerned with divine matters.

Language itself was divine. And metaphor played an incredibly important role, as signs and symbols were all-important.

Vico singles out the bolt of lightning, for example, as the first sign of Jupiter. This is simply to show how terrified these primitive people were in the beginning. They lived in caves, like Home’s Cyclops. This was a period of epic wandering. Man was chaotic and unruly. The Muse, through her instruction, tamed him. Such are the divine origins of language.

Joycean scholars have had great fun deciphering the various myths from the Bible and Antiquity that register in Book 1 of Finnegans Wake. It is indeed a really funny book – as Joyceans constantly highlight –full of puns referring back to famous figures, such as the Duke of Wellington and Ishtar, the ancient Babylonian Goddess of Love and War, and the Scottish empiricist philosopher David Hume, and so many more.

It is a great sprawling narrative divided into eight chapters each one given over to one of the major characters who are called the Earwickers. Father and Mother – Humphry and Anna, and their three siblings Shem, Sham and Issy. The first chapter is a kind of prelude given over to history and the origins of the Muse.

Beckett in How It Is begins his novel in similar fashion. Just as Joyce derives his ideas from Vico on the origins on human societies, Beckett too points to the Muse at the very beginning of the novel by starting with an invocation.

Although unconventional, as you would expect from Beckett, that he uses the structural form tells us everything.

The great Russian comparatist Mikhail Bakhtin, in The Dialogical Imagination (1975), is at pains to point out the origins of the novel as a genre and its debt to epic poetry, from which it took many structural features. Most novels are of tri-partite structure in theory, as Aristotle in his Poetics asserts, telling of events before, during and after – which is exactly what Beckett does in How It Is: events before Pim, with Pim and after Pim.

Who is this Pim, you might be asking? To answer this we move on now to Vico’s Second Age, which is given over to violence.

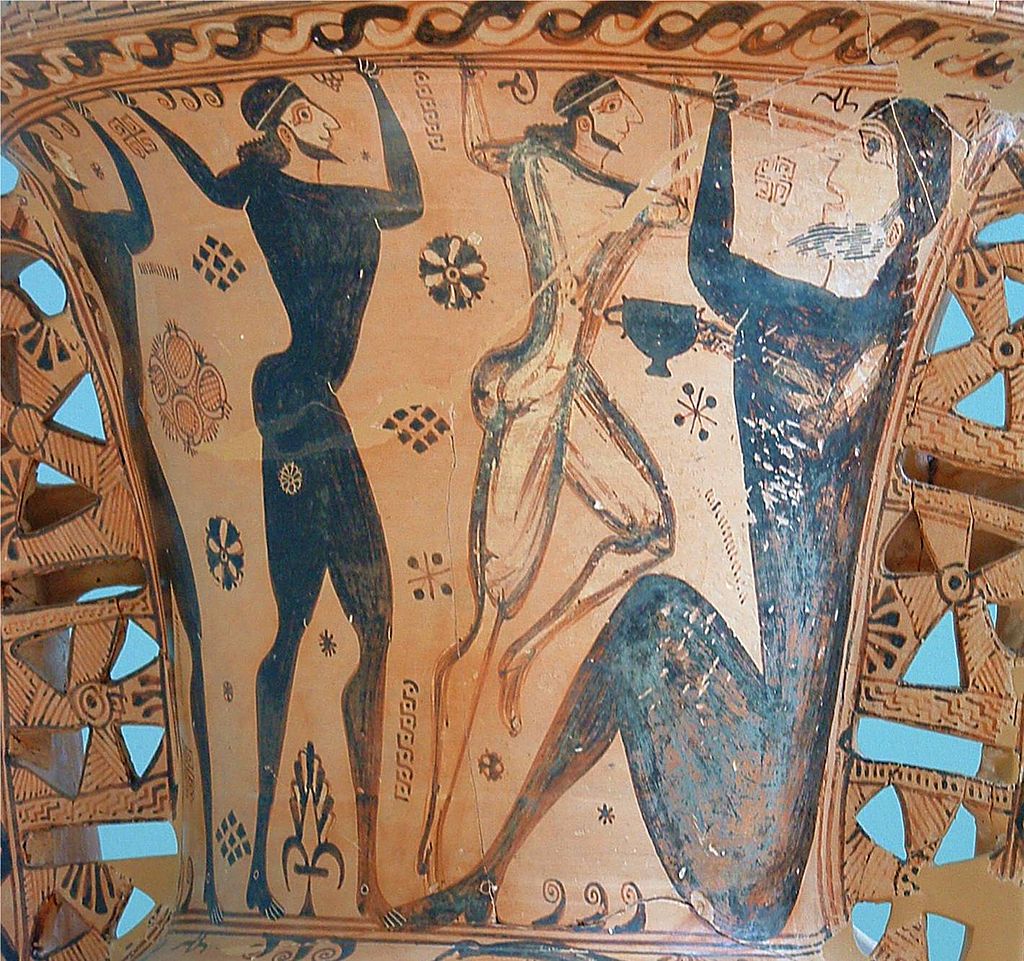

Odysseus and his crew are blinding Polyphemus. Detail of a Proto-Attic amphora, circa 650 BC.

Female Domination

Recall my story with girl Number Two? How She kicked my sorry little ass! Yes, I am talking about Female Domination of the male species, just as I spoke about Male Domination of the female in the First Age. This is karma. Although with Beckett the characters are practically sexless.

Similarly, Joyce parodies Hitler and the Nazis in Book 2 of Finnegans Wake, who were on the rise during Joyce’s lifetime. Book 2 of Finnegans Wake is full of wonderful puns at the expense of the Nazis, referencing particularly their atrocious treatment of Jews.

Beckett in How It Is uses the most crude and forceful comedy. It is truly grotesque. The only comparison that I can think of in literature is a Satyr play – bringing us back to Ancient Greece.

There is only one surviving Satyr play: The Cyclops by Euripides. Anyone who is familiar with this hilarious text will be aware that it is a parody of Homer’s Odyssey. A grotesque parody in the style of Rabelais.

Essentially, Euripides takes the myth of Zeus and Ganymede which sees the king of the gods having his way the beautiful youth.

Ganymede is synonymous with the submissive person in an amorous relationship. The Bottom, in short. As opposed to the Top. We here use the language of S&M, which is what we are talking about. Bottoms and Tops. Dominants and submissives. This is what Beckett is obsessed with in How It Is. This is what I have come to call the maths of rejection.

Set Theory

As the novel progresses, Beckett becomes more and more obsessed with the numbers Three and Four. In fact the quartet, not the trilogy, is the ideal set.

I am using the mathematical term now, taken from set theory. As this is how Beckett chooses to enter into the subject matter. It went on to become a major obsession of his during his later writing career. Consider there were two decades between the publication of How It Is in 1961 and his play Quad, completed in 1981, although tit wasn’t published until three years later.

Beckett spends the greater part of parts 2 and 3 of How It Is going over the innumerable permutations of movements. We are back with girlfriends One and Two, which started this small discourse on Love and Literature. Remember 1 + 2 = 3. Therefore, if we were to progress to 4, that would mean a return to 1 – to my mind anyway. Meaning I would have to become the bastard again.

Beckett uses the terms Victim and Torturer. These are the two modes of so-called human behaviour. In Beckett’s world, or, at least in the universe of How It Is, you are one or the other. I wonder which one are you?

This is a slight simplification, as the movement of the couples in How It Is is in permanent flux.

Beckett was also obsessed by Heraclitus and Democritus, the crying and laughing philosophers who form the two masks of theatre showing both aspects, extreme poles of human nature: the Tragic and the Comic; the legacy of the Ancient Greeks, which Beckett – without a doubt the greatest playwright of the twentieth century – revitalized.

What other playwright uses farce to such a violent advantage? Think of the Tramps Estragon and Vladimir contemplating hanging themselves from the tree, as a form of entertainment in Waiting for Godot; Nag and Nell consigned to the dustbins in Endgame; or Winnie up to her neck in it in Happy Days.

In all the unforgettable imagery conjured in Beckett’s theatre we find unforgettable visual metaphors encapsulating, in their simplicity, human tropes, which endure eternal.

Inspired by Baudelaire, Peter O'Neill fumes about "The shitty structures which we maintain and perpetuate. / Up to our necks in it." of climate changed world.https://t.co/LQznExkcVq@whittledaway @PaddyWoodworth @think_or_swim @broadsheet_ie @wadeinthewate11 @EllieKateLily

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) April 14, 2021

In this Beckett is the poet of catastrophe and disaster, a role he inherited from the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867).

Baudelaire was the first to mine the negative aspect in man to such a profound and relentless degree, in this sense Beckett is really his doppelgänger. It was Beckett’s genius to align himself so much to the dark side, as it were, which Baudelaire had ploughed so successfully in Les Fleurs Du Mal.

Featured Image: Louis Jamnot (1814-1892), Le Vol de l’âme