Around the beginning of the second century AD, the Greek writer Plutarch unknowingly created the spark for a flame of artistic inspiration which, not unlike the notion of the ancient Olympic torch, has transcended millennia until today. He might, perhaps, have nourished the expectation that his work’s renown would outlive him, but he could not have imagined that his words would be traced through the 20th century poetry of Cavafy to the 21st century songs of Leonard Cohen and Laura Marling. And yet, in a single stunning example of ancient influence and contemporary Classics, one particular story of his has been read, performed, spoken, sung, enjoyed, downloaded, streamed and reflected on in a chain of inspiration which spans over a century of creativity. The remarkable longevity of one small digression in the mass of Plutarch’s extant work demonstrates beautifully the basic humanity which has connected us from antiquity to now, reflected and refracted through the lens of varying personal and societal perspectives. As a result, the historic loss of Alexandria has become, paradoxically, our cultural gain.

Mark Antony Offering a Sacrifice.

The spark in question is embedded in Plutarch’s account of the downfall of Mark Antony, Roman general and lover of the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, at the hands of the future Emperor Augustus. Antony’s defeat at the Battle of Actium in 31BC was already distant history in Plutarch’s time, but its seismic influence on the governance of Rome – replacing the failing Republic with the dictator-led regime of the Empire – would have been ubiquitously understood. Plutarch, however, was not in the business of writing purely historical accounts: his Lives, under which Mark Antony’s destiny is recorded, are self-proclaimed biographical character studies rather than dispassionate factual recordings; as such, curious digressions and titbits of hearsay weave their way through his narratives. One such side-story is related in the description of Mark Antony’s final night in Alexandria before his monumental defeat at Actium:

ἐν ταύτῃ τῇ νυκτὶ λέγεται, μεσούσης σχεδόν, ἐν ἡσυχίᾳ καὶ κατηφείᾳ τῆς πόλεως διὰ φόβον καὶ προσδοκίαν τοῦ μέλλοντος οὔσης, αἰφνίδιον ὀργάνων τε παντοδαπῶν ἐμμελεῖς τινας φωνὰς ἀκουσθῆναι καὶ βοὴν ὄχλου μετὰ εὐασμῶν καὶ πηδήσεων σατυρικῶν, ὥσπερ θιάσου τινὸς οὐκ ἀθορύβως ἐξελαύνοντος: εἶναι δὲ τὴν ὁρμὴν ὁμοῦ τι διὰ τῆς πόλεως μέσης ἐπὶ τὴν πύλην ἔξω τὴν τετραμμένην πρὸς τοὺς πολεμίους, καὶ ταύτῃ τὸν θόρυβον ἐκπεσεῖν πλεῖστον γενόμενον. ἐδόκει δὲ τοῖς ἀναλογιζομένοις τὸ σημεῖον ἀπολείπειν ὁ θεὸς Ἀντώνιον, ᾧ μάλιστα συνεξομοιῶν καὶ συνοικειῶν ἑαυτὸν διετέλεσεν. (Plutarch Life of Antony, 75.3-4)

And it is said that during the middle of that night, as the city lay subdued and downcast from fear and expectation of what was to come, the harmonious sounds of all manner of instruments could suddenly be heard, along with the sound of a crowd of Dionysian revellers and satyr-like carousers, as if some Bacchic band was processing out of the city in a raucous fashion: their collective course seemed to take them through the middle of the city to the outer gate facing the enemy; at this point the noise, which had reached its peak, fell away. It seemed to those who analysed this sign that the god to whom Antony continually sought to compare and attach himself was leaving him.

This folktale-like aside could be dismissed simply as adding little more than narrative colour to the portrayal of Antony’s demise. And yet, this physical representation of Antony’s personal loss also serves as a powerful reminder of the inevitability and ineluctability of a foregone fate. The god, representing the general’s aspirations and inspirations, deserts him in a flutter of fictitious revelry; the irony of the joy in the Bacchic procession and its solemn symbolism is all too present. The nuance of Plutarch’s story, it seems, lies in the act of reconciling with an unavoidable destiny; it is theme which fans the flame of inspiration in modern artistic endeavours.

Constantine Peter Cavafy 1863-1933.

The primary reinterpretation of Plutarch’s curious digression appears in Constantine Cavafy’s 1911 poem The God Abandons Antony. Cavafy’s frequent evocations of influential figures and events from antiquity in his poetry often serve as a mechanism for exploring wider, more universal moral and psychological themes – as is expertly demonstrated in another of his poems, Ithaka – and in this poem, too, the past is blended eloquently with the present. Where Plutarch’s biographical purpose constrained him from offering explicit comment on the story he presents, Cavafy’s poetry freely re-interprets the situation in the form of a didactic monologue:

When suddenly, at midnight, you hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive—don’t mourn them uselessly.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving.

Above all, don’t fool yourself, don’t say

it was a dream, your ears deceived you:

don’t degrade yourself with empty hopes like these.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

as is right for you who proved worthy of this kind of city,

go firmly to the window

and listen with deep emotion, but not

with the whining, the pleas of a coward;

listen—your final delectation—to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession,

and say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.

(trans. Edmund Keeley & Philip Sherrard.)

Knowledge of the poem’s classical context clearly identifies the addressee of this moral admonition as being Mark Antony, but the poem can be read from two perspectives: one as a dramatised portrayal of a piece of historical biography, and the other, divorced from its ancient inspiration, as an edification of endurance, that most human of experiences. The former poignantly captures the mood of despair, realisation and tragic inevitability in Plutarch’s original story, set against the background of Antony’s approaching demise. The encouragement of stoicism and acknowledgement in the face of defeat chimes particularly with Plutarch’s own presentation of Antony on the eve of the battle: in the first part of the chapter narrating the rumoured Dionysian revelries, the biographer describes how Antony, having decided to mobilise his attack on Octavian the following day, orders a lavish feast on the premise that he did not know whether he would ever be able to do so again. In the second, universalised interpretation of this poem, we are encouraged to view the ‘invisible procession’ as a metaphor for realising and confronting our destinies. In turn, the desired stoicism in recognising that our futures are uncertain and never fully under our control is as pertinent now as it was to Antony. Cavafy, in a style similar to psychologists and cognitive behavioural therapists today, encourages us to replace the ‘what ifs’ with the ‘now whats’ when coming to terms with complications in our lives; in his reinvigoration of Plutarch’s words, therefore, the poet expertly blends specific story and general advice, ancient context with modern relevance.

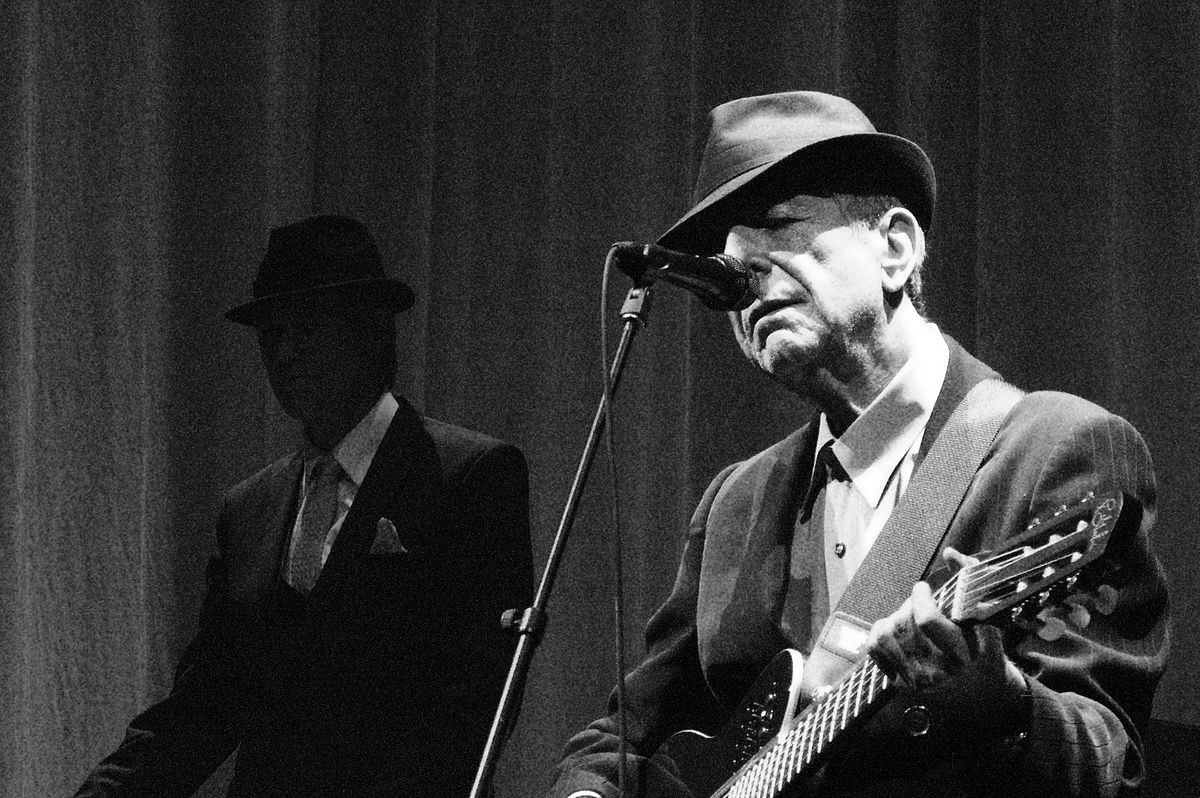

Almost a century later, the next reincarnation of Antony’s loss was brought to life by another poetic genius in the form of Leonard Cohen’s song Alexandra Leaving. Mirroring Cavafy’s simultaneously faithful and creative relationship with his ancient model, Leonard’s lyrics are at once recognisable to those familiar with his poetic source, and yet strikingly innovative in their new shape.

Suddenly the night has grown colder

The god of love preparing to depart

Alexandra hoisted on his shoulder

They slip between the sentries of the heart

Upheld by the simplicities of pleasure

They gain the light, they formlessly entwine

And radiant beyond your widest measure

They fall among the voices and the wine

It’s not a trick, your senses all deceiving

A fitful dream, the morning will exhaust

Say goodbye to Alexandra leaving

Then say goodbye to Alexandra lost

Even though she sleeps upon your satin

Even though she wakes you with a kiss

Do not say the moment was imagined

Do not stoop to strategies like this

As someone long prepared for this to happen

Go firmly to the window. Drink it in

Exquisite music. Alexandra laughing

Your first commitments tangible again

And you who had the honor of her evening

And by that honor had your own restored

Say goodbye to Alexandra leaving

Alexandra leaving with her lord

Even though she sleeps upon your satin

Even though she wakes you with a kiss

Do not say the moment was imagined

Do not stoop to strategies like this

As someone long prepared for the occasion

In full command of every plan you wrecked

Do not choose a coward’s explanation

That hides behind the cause and the effect

And you who were bewildered by a meaning

Whose code was broken, crucifix uncrossed

Say goodbye to Alexandra leaving

Then say goodbye to Alexandra lost

Say goodbye to Alexandra leaving

Then say goodbye to Alexandra lost

Linguistic resonances to Cavafy abound: phrases such as ‘exquisite music’, ‘one long prepared’, ‘go firmly to the window’, and, critically, ‘say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving’ are all re-worked into Leonard’s musical response, weaving their way through the fabric of the work to ground it unmistakeably in its origins. The themes of stoicism in the face of loss or change are also concurrent with his 20th and 2nd century sources; in essence, at least, Leonard Cohen’s interpretation stays close to its predecessors. However, it is the striking innovation of replacing the physical Alexandria with an abstract name, Alexandra, that gives the song its own life independent of its sources. Cohen’s poetic artistry lies in his concealment of exactly who Alexandra is and what she represents: instead, snapshots of vague reminiscence are brought sharply into focus when interrupted suddenly by didactic commands familiar from Cavafy. It is as if he descends momentarily into reverie, only to be dragged back to the present by the imitations of his poetic source. Through the deliberate mystery invested in his subject, Cohen is able to generate in the listener a milieu of emotions – nostalgia, wistfulness, longing, regret – all brought together by the abstract concept of ‘Alexandra’. As such, the exact context of Alexandra’s leaving is laid open for us to decide, with some fascinating results. A brief glance at online forums discussing the meaning of song lyrics reveals that many have sought to tie the song to their own particular experiences of love, loss, and betrayal, while others acknowledge that the lyrics have taken on different meanings over time; one man, for instance, was particularly struck by the song’s affinity with his emotional state after giving his daughter away on her wedding day. In this way, Cohen’s boldest innovation – the abstract Alexandra – becomes simultaneously his tightest bond with its predecessor; as in Cavafy’s poem, Antony’s plight is universalised, but this time through the lens of another most human of emotions: love.

The final link in this intriguing chain of interpretation comes in the form of Laura Marling, a singer-songwriter who, not unlike Plutarch himself, invests an element of biography into her work. Her song, Alexandra, is as much a tribute to Leonard Cohen after his 2016 death as it is to Alexandra Leaving in particular, while Marling has herself described the 2020 album in which it falls, Song For Our Daughter, as ‘essentially a piece of me’. With pride of place as the opening track, Alexandra offers a fascinating new perspective on the Alexandra of Cohen’s song, taking her abstract and forming it into a tangible, intelligible persona. Crucially, Marling’s take offers something which Alexandra Leaving could not: a female voice, rather than a perception of the situation necessarily filtered through Leonard’s ‘male gaze’.

What became of Alexandra

Did she make it through

What kind of woman gets to love you?

Wrote us all a little note

Nothing left to lose

What kind of woman gets to love you?

I need to know

Where did Alexandra go?

Alexandra had no fear

She lived out in the woods

She’d tell you what you’re doing wrong

If she thinks she’ll be understood

Pulls her socks up to her knees

Finds diamonds in the drain

One more diamond to add to her chain

I need to know

Where does Alexandra go?

Where did Alexandra go?

It won’t change how I’m feeling

You can try to help me understand

If she loved you like a woman

Did you feel like a man

I need to know

Where did Alexandra go?

Where did Alexandra go?

You had to say

You feel too bad

You could not bear

Be understood

I had to try

A fuck to give

Why should I die

So you can live

What did Alexandra know?

What did Alexandra know?

What did Alexandra know?

The sense of inevitability which permeated Plutarch and Cavafy finds its place once more in this work, but it does so instead through the juxtaposition of gender and love, while Marling’s more overt debt to Cohen provides the frame within which to discuss wider issues of masculinity and self-discovery. When interviewed about the meaning of Alexandra, Marling emphasised her fascination with Leonard Cohen’s attitude towards women as a leading part of the song’s inspiration, but it feels more like a wider portrait of the negative tropes of masculinity and love. My own interpretation of the song rests on Marling questioning a male interlocutor about the fate of Alexandra and his relationship with her, asking powerful questions like ‘what kind of woman gets to love you?’ and ‘what did Alexandra know?’. As more details about Alexandra’s character are revealed, portraying her as free-spirited and forthright, it sets up the contrast between masculine and feminine perceptions of love: ‘if she loved you like a woman / Did you feel like a man’. The song’s climax, however, is when the male perspective is revealed. ‘You had to say / You feel too bad / You could not bear / Be understood’ highlights the all-too-prevalent issues of masculinity as meaning emotionally closed-off, especially when confronted with a woman who would speak her mind and challenge his behaviour.

For me, the central lines – ‘why should I die / So you can live’ – embody the frustration of women (in this case, ‘Alexandra’) feeling compelled to mute their own needs in order to accommodate the emotional detachment perpetuated by norms of masculinity. Although Plutarch himself may have been far from Marling’s mind in the composition of Alexandra, his story’s themes of self-reflection and facing up to an unavoidable fate resonate throughout the song, only this time the sense of inevitability is linked to the very current issue of gender conventions and their consequences.

Stoicism, introspection, loss, endurance: these are universal ideas which, after finding their place in a smattering of ancient lines, have been reincarnated in ever more innovative ways through the mediums of modern poetry and song. In this way, the spark of Plutarch can be found, via a convoluted relay of beacons through Constantine Cavafy and Leonard Cohen, in the flame of Laura Marling, even though their ancient and modern contexts bear no direct resemblance to each other. There is much in our world which can be attributed – directly or indirectly – to antiquity, but there is little so poignant as this literary lineage of Alexandria’s loss.