What one leaves behind. I guess a lot of stuff. If over the last few years you have passed Bloom’s Lane, just across the Millennium Bridge on the north side of the River Liffey, you may have noticed a familiar figure. Sometimes standing on the bridge, other times reading from a bundle of newspapers and taking coffee in front of one of the four Italian joints adorning this little square, carved out by Mike Wallace in the early 00s.

The big black coat only came off on rare summer days, and with a wide-brimmed black hat ever-present, he earned the nickname: ‘the Zorro of the Liffey’.

This was Gerard Dowling, the Dublin artist mainly known for his twenty-year, controversial residence on 47 Middle Abbey Street, a four-story Georgian townhouse, right in the heart of the north inner city. He lived out his afternoons and evenings in this new part of town, full of recently-arrived Dublin residents; an aspect not to be overlooked, considering Gerard’s peculiar preference for solitude. He shunned empty pub conversations.

Anyone who knew Gerard also knew where and when to find him: from 3pm in the Italian Quarter, any day of the week. After that, as the restaurants closed, he would say ‘ciao’, and proceed swiftly south across the bridge, towards his last residence in Harold’s Cross. Gerard was going to work.

His life was a puzzle to those who knew the many ambiances he lived simultaneously among. Between his studio residence and the Italian restaurants, the bottom of the Liffey at low tide, or Focus Ireland in Temple Bar where he lunched every day, his unusual appearance made him a target of curiosity, at times openly unwelcomed.

Originally from Ballyfermot, he entered a seminary at the age of fifteen. It was the quickest way to get out of school he said. Despite this being his choice, it was, nonetheless, a period in his life he only talked about reluctantly.

Bit-by-bit, combining precious skills learned from an inventive father (including welding, metal-work and photography), with a lifelong capacity as an autodidact, he developed into the audacious artist frequenters of his atelier knew so well.

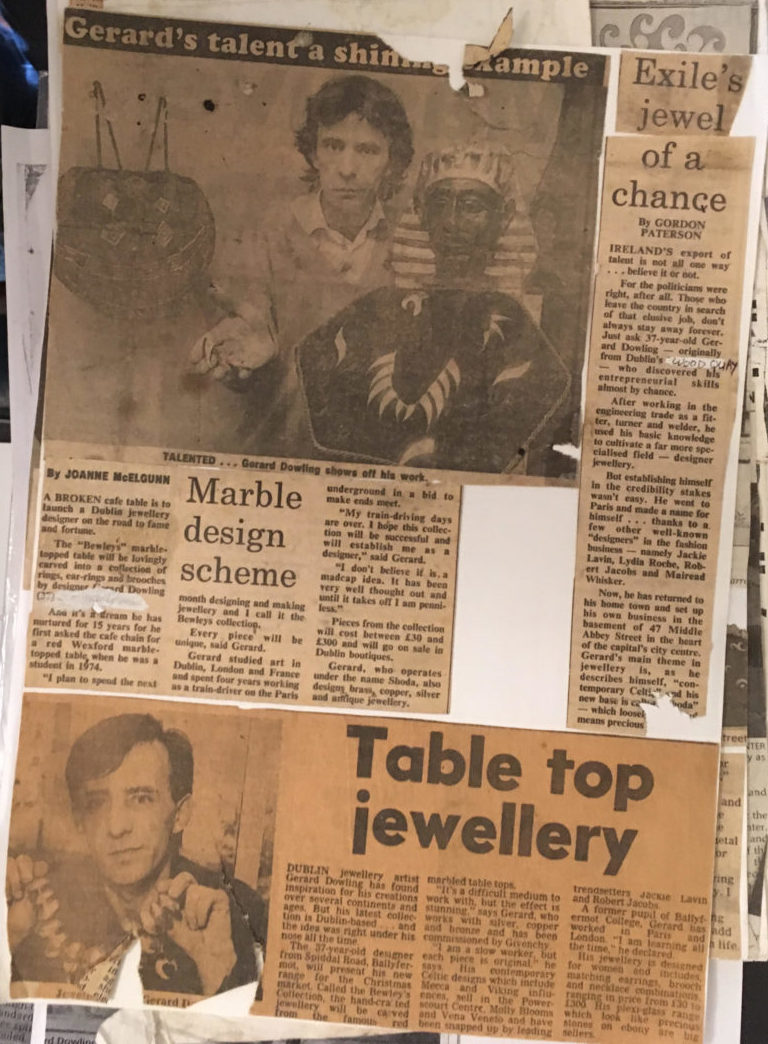

He moved to London in 1969 with a desire to interact with the arts scene around Carnaby Street  and Piccadilly. He wound up working as an Underground train driver, lasting two months on the job before he was sacked for smoking dope. Two years later he was back in Dublin for a brief period of time, before setting off to Paris. There he enjoyed success as a jewellery designer, working for the likes of Givenchy and Bijou Fantasies.

and Piccadilly. He wound up working as an Underground train driver, lasting two months on the job before he was sacked for smoking dope. Two years later he was back in Dublin for a brief period of time, before setting off to Paris. There he enjoyed success as a jewellery designer, working for the likes of Givenchy and Bijou Fantasies.

Returning to 1980s Dublin, he attempted, unsuccessfully, to keep going with jewellery design; in the basement of that famous house on Abbey Street, which prior to him taking up residence there had served as his father’s place of business.

In an Evening Press article from February 9th, 1990, he complained: ‘Thieves are robbing me of livelihood’, after a spate of robberies left him without many of his tools.

As time went by, with other tenants leaving the premises and not being replaced, he slowly made use of the upper floors. Eventually he had the whole building to himself, which was perfectly suited to producing and exhibiting his unique works of art.

Most of his work was recycled art, reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp’s ‘ready-made’ pieces; an artistic direction he would have encountered regularly in Paris and London, but which was extremely scarce, if non-existent, on the Dublin scene at the time.

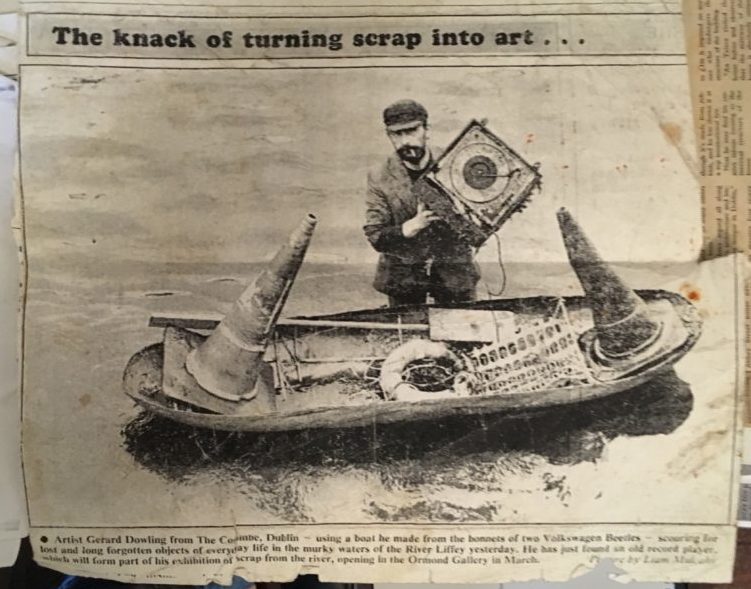

In the early 1990s he would regularly climb down to the River Liffey bed at low tide, also using a small raft, improvised with his father out of two Volkswagen Beetle bonnets. He would rescue various leftovers the city had spat out, from what he referred to as ‘the cradle of Dublin.’

There he found: traffic cones, bicycle parts, fragments of the Halfpenny Bridge, record players, and shopping trolleys. He once publicly complained about the danger posed by those trolleys to inner city kids diving into the river. But mainly he was exposing environmental neglect. The river had become an endless dump for raw materials, now at his disposal, reflecting the city above’s social and economic characteristics.

He often remarked on the increasing pile-up of mobile phones, and even wedding rings, discarded after break-ups.

By then 47 Middle Abbey Street had become, in fact, one of the very few remaining non-institutionalised art spaces. Many recall various parties and openings regularly taking place on its different levels, largely ignored by Ireland’s official art societies and institutions.

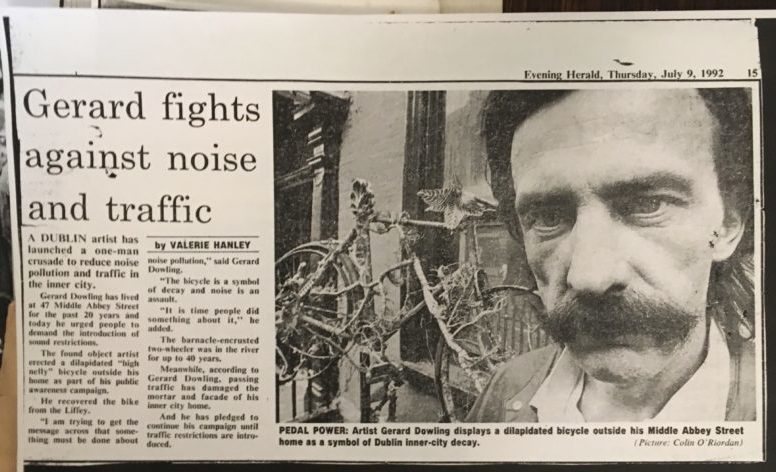

Institutions would, however, eventually take notice of Gerard Dowlling. After a misunderstanding with ‘The Sculpture Society of Ireland’ (now known as‘Visual Artists Ireland’) in 1991, when a dilapidated bicycle covered in seaweed and barnacles hanging from the front of the house was mistakenly assumed by journalists to belong to the Society’s official Sculpture Trail. But Gerard vehemently denied any participation.

The furore placed his residency on Middle Abbey Street under scrutiny. Dublin City Council, and private interests, were eager to take possession of a valuable property. At the time Dublin was gearing up for the big sell-offs of property, paving the way for the Celtic Tiger, and becoming more and more of consumer society. This early plunder of the city’s architectural, social and artistic heritage passed unobserved by most.

Dublin City Council, and private interests, were eager to take possession of a valuable property. At the time Dublin was gearing up for the big sell-offs of property, paving the way for the Celtic Tiger, and becoming more and more of consumer society. This early plunder of the city’s architectural, social and artistic heritage passed unobserved by most.

It led to a ten-year-long legal battle, pitting the artist against Dublin City Council. It ended seven-years-ago with Gerard forced out of the premises, although he did receive financial compensation as part of a settlement.

Over that time, he also contended with mental health issues, mainly derived from his sister’s murder during the 1970s, a trauma he was only able to speak about openly in recent times, along with other episodes from his youth, which he usually attributed to ‘bullying.’ Despite these challenges, Gerard never stopped working on his art, even up until his last days.

Artist Gerard Dowling hangs from a harness painting the outside of his house in Dublin City Centre, entitle”Tsunami Now”. 21/5/2005 Photo Photocall Ireland

From being fined for painting bubble gum onto footpaths, to highlighting Dublin’s decay, and assembling massive sculptures made from traffic cones; or adorning barbed-wire Christmas trees with abandoned soothers, and using debris from motor cars to form African-inspired masks, his aesthetics never ceased to evolve. He never settled in a comfort zone derived from the guidelines seemingly accompanying contemporary art exhibitions.

In the midst of that variety of forms, and styles, certain motifs recur. From his jewellery design he developed and enhanced fractal-like-Celtic-motifs, which reached a height expression in a collection of twelve paintings, or collages, produced over the last twenty years.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”52″ gal_title=”Gerard Dowling Article”]

His late work reveals an abiding love of science, particularly the concept of energy conservation, and anthropological studies of prehistoric tools seen as the origin of human expression. He produced miniature dolmen-like structures, carving in stone to create perfect surfaces for each to be stacked on top of the other.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=”54″ gal_title=”Gerard Dowling Article II”]

Powder resulting from the process was combined with glue and napkins – pilfered from the Italian restaurants – forms five square pieces of sculptural-relief, resembling volcanic landscapes. Together with varied photographic images and an array of newspaper clippings, it surveys a life spent on the verge of notoriety.

I like to remember what cannot be left behind materially. One of Gerard’s favourite recent activities over long afternoons spent in the Italian Quarter had been to draw convoluted patters with chalk on the pavement of the Square. Stepping back, he liked to observe who would walk and thus ruin his drawings; or those sensitive souls who would take notice of them, and kindly offer his ephemeral shapes a slight extension to their lives; at least until the first rain shower, or the incessant flow of early morning commuters.

©Andrea Romano

Feature Image: Julien Behal Photography