On April 30th, acting Minister for Agriculture Michael Creed defended Ireland’s agricultural sector,[i] claiming we are the second most food secure country in the world. What Creed seems to have been referring to was an Irish independent article from October 2019, saying Ireland had moved from first place to second in a Global Food Security Index.[ii]

In so doing, Ireland had been overtaken by Singapore, a micro state that imports over 90% of its food. You might ask, how is it possible that this island of concrete was adjudged to be the most food secure place on the planet?

Singapore, ‘the world’s most food secure country’.

On closer examination, it seems this “research” had been sponsored by Corteva Agriscience, one of the largest producers of pesticides in the world, and now a subsidiary of DowDupont after a merger with Dow Chemical, (the corporation responsible for the Bhopal Disaster in India 1984). Such vested interests cannot be trusted as a reliable source in assessing the food security of nation states.

The fact that Singapore is ranked highest in a food security index sponsored by an agri-chemical multinational should come as no surprise, as these chemicals are much more likely to figure in industrially produced food systems, traded on a global market, rather than localized, subsistence food systems.

It also comes as no mystery to find the Irish independent presenting this highly dubious study as fact. That newspaper has historically represented the interests of the comprador, or broker capitalist class in Ireland; that revolving door between agribusiness, finance and politics, servicing the multinationals that have located in Ireland.

Moreover, Micheal Creed has a track record of presenting erroneous research to the Dáil regarding emissions from Ireland’s fast-expanding dairy sector.[iii]

Food security in this scenario equates to commodities being traded on a global market with minimal restrictions. The evaluation is predicated on current availability, price and diversity of food consumed – regardless of productive factors or supply chain interference. It takes no account of the environmental or social consequences of this supply line, or any risks lying further down the line, whether a hard Brexit, a global pandemic, or that the global food system has eroded a quarter of all arable topsoil on the planet since the 1950s.[iv]

Despite supposedly being number two in the world in terms of food security, Ireland now imports the majority of its potatoes and nearly all its wheat flour; the main staple carbohydrates of the people of Ireland.

The Teagasc Consensus

A large part of the belief in distortions like these can be attributed to the neoliberal religion of free trade, which is engrained as a belief system in a great number of Irish farmers.

Over the course of the twentieth century, the adaptation of new and increasingly expensive inputs into agriculture have been sold as ‘progress’ to farmers. Numerous chemicals and pharmaceutical companies, including SmithKline, Pfizer, Merck, Schering Plough and Roche located their manufacturing facilities in Ireland during the 1960s and 70s, availing of lax or non-existent environmental regulation and lower labour costs. They stayed because of an attractive corporate tax regimes and unrestricted interference in Ireland’s educational system. By the turn of the twenty-first century they accounted for nearly seventy percent of global pharmaceutical output.[v]

These multinationals have helped the Irish state to adopt an increasingly intensive, highly specialized monoculture agricultural system, geared towards the export market.

Traditionally, farmers have gone along with this because of the developmental rhetoric and of course, generous EU subsidies.

Also crucial to manufacturing consent has been the educational apparatus of Teagasc, the state research centre for agriculture. Teagasc uses science selectively to the end of export intensification.

Connected to the revolving door between chemical and pharmaceutical multinationals located in Ireland, Teagasc and other state educational institutions have effectively locked farmers into an unsustainable, high-input agricultural model, based on the latest bio-technological ‘fixes’ formulated by the agri-chemical industry.

The end result is scientistic rather than scientific, meaning science is adopted in a cosmetic manner, to provide technical short-term fixes within a strictly liberalised market paradigm.

A truly scientific approach, which is essential in the face of irreversible climate change, requires rigorous philosophical as well as technical inquiry, taking into account all of the parts involved in a system and their effects. This is a thorny path to embark upon, especially when multinational interests are threatened.

Irish state education, and Teagasc in particular, indoctrinates a free market ideology into young people. This includes the Law of Comparative Advantage, which involves specialization in one industry over others, for the purposes of international trade. This is the central tenet of the state’s agricultural policies, and the cornerstone of Teagasc’s educational institutions.

The Law of Comparative Advantage has long been subjected to criticism from other schools of thought such as Development Economics: most notably the Singer-Prebisch thesis, which demonstrates that the terms of trade between countries producing primary products deteriorates over time, relative to countries producing manufactured goods.

Notably, this economic ‘Law’, was formulated by British Economist David Ricardo in 1817, when the Spanish colonies in the Americas were in the process of becoming independent republics. Spain’s loss was Britain’s opportunity, as ‘free’ trade doctrines became the rationale for unequal exchange between the global North and the global South, then as now, keeping wealth flows disproportionately northwards.

Now in the former British colony of Ireland the main farmers’ lobby, the IFA, maintains the consensus around globally traded commodities, successfully convincing many smaller farmers that their interests are joined to large scale beef and dairy producers.

Just recently the IFA managed to compel acting Minister Creed to continue with live exports to Turkey, Algeria and Libya as a way of stabilizing prices.[vi]

Yet many farmers are discovering that they have given away too much autonomy to the IFA and their political patrons in Fine Gael. Some small farmers broke away from the IFA to form the Beef Plan Movement, which challenged export monopolies from 2018, but the Movement seems to have dissipated.

Now some disillusioned farmers are beginning to see the EU’s CAP as the source of their problems, and are calling for an ‘Eirexit’.[vii] However, while free trade agreements in the EU and other consumer markets are a vehicle for the current model, the driver has long been the Irish State.

Source of the Problem

With many farmers now in grave financial difficulties, it has become apparent that the source of our agricultural difficulties lies in international free trade arrangements, European or otherwise, being used by the State and accepted without question by farmers’ lobbies in the name of ‘progress’.

There was nothing inevitable about European integration pushing Ireland so far past its ecological carrying capacity in terms of agriculture: it came from the Irish state’s pursuit of European integration and other free trade arrangements.

During the 1970s and 1980s, the Irish State pushed to clear wildlife from farms, even if the financial incentives came from EU grants. It is the Irish State which continues to push for export intensification through its Food Harvest 2020 and Foodwise 2025 schemes, seeking markets far beyond the EU. Ireland is now the second largest exporter of infant formula in the world, its largest market being China.[viii]

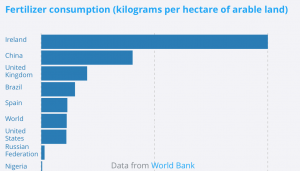

A food system that is so integrated into global market chains has brought increased levels of monoculture specialisation in beef and dairy, severely diminishing the diversity of food produced [ix], and depending not only on chemical inputs ,which pollute our environment and destroy biodiversity, but also on imported animal feedstuffs.

The dairy industry has grown by 27% [x] in just five years and continues to expand, far exceeding the carrying capacity of the grassland it relies on. Due to homogenization, the supply chain of pretty much all Irish butter and non-organic dairy produce contains on palm kernels, and genetically modified, Roundup-Ready soya and corn.

This amounts to an appropriation of land, labour and water resources from the global South, causing deforestation in tropical rainforests, erosion of topsoil which takes thousands of years to form; as well leading to the extinction of animal and plant species.

The successive crises that these policies have led to in Ireland have been misrepresented as ‘fodder’ crises. They are in fact over-intensification crises, arising from destructive free trade policies which have pushed the island of Ireland past its agricultural carrying capacity.

These are a reoccurring themes in Irish history. The difference between today’s and the crises of the eighteenth and nineteenth century is that Ireland is no longer bottom of the economic hierarchy in the global economic system. As a result, the environmental burden can be externalised to peripheral parts of the world, especially through feed imports.

Inside Ireland’s largest milking machine. Henry Clarke (wikicommons).

A New Way Forward

The progress of the so-called ‘Green Revolution’ in agriculture from the 1940s is beginning to unravel. Short term bio-engineering fixes are spiralling out of control. A continuous stream of newly engineered GM crops – which can withstand higher concentrations of agri-chemicals – are being rolled out in response to new herbicide resistance in weeds which make the existing chemical concentration of previous GM varieties ineffective. The result is higher doses of chemicals in our food chain and mass extinction of pollinating insects and soil microorganisms.

The limits and consequences of the industrial model of agriculture is now evident from a food security standpoint as well as in terms of the environment. The science behind our agriculture needs to involve a whole systems approach that takes into account all of the ecological consequences of globalized food production, and which places soil conservation and renewal at its core.

At present, this is missing entirely from Teagasc’s educational apparatus as the current food production model is not circular, but extractive: heavily dependent on imported inputs which cause deforestation, topsoil degradation and extinction of species in other parts of the world, as well as wreaking havoc on biodiversity and water quality within Ireland.

In the wake of Covid-19, a future roadmap is in the hands of whoever dares to seize the moment. The epidemic has occurred in the wake of years of environmental campaigning and the farm to fork strategy [xi], which has been pushed through at European level. This reflects a growing recognition of the limitations of the global industrial food model at the highest levels of political power.

This crisis of international capitalism is a real opportunity for small producers to adopt more localized regenerative agricultural systems, which are embedded in community and work with natural ecosystems instead of attempting to dominate them. In these kinds of systems, farmers and communities of farmers produce foodstuffs suitable to their bio-regions, sequestering carbon in the soil.

These kinds of systems generate their own inputs, freeing farmers from the clutches of the agri-chemical industry. In this kind of scenario, farmers produce a healthy diversity of food for their communities, instead of monoculture commodities for cargo ships.

In order to achieve this, however, we require a complete overhaul of deep-seated beliefs about farming which have been perpetuated by state propaganda, the educational apparatus, and the media.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization now recognises agri-ecology as the way forward for developing food security in the face of climate change. We must fight State policies which prevent a regenerative agriculture. Not only is this achievable, it is essential.

[i] VideoParliament Ireland, Deputy Holly Cairns – speech from 30 Apr, YouTube, 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8PrwuHgRxPM&feature=youtu.be&fbclid=IwAR16-ozAjJzFY_iF2fWI8jr0yu0ydOZCdse5vJxvXkavGEltsHoOMAZAM2g

[ii] Margaret Donnelly, ‘Deputy Holly Cairns – speech from 30 Apr 2020’, Irish Independent, October 16th, 2018, https://www.independent.ie/business/farming/news/world-news/ireland-slips-to-second-in-the-world-for-food-security-37425858.html

[iii] Press Release, ‘An Taisce has called on Minister Creed to retract misleading Dáil statements on rising dairy emissions’, 25th of June, 2018, https://www.antaisce.org/articles/an-taisce-has-called-on-minister-creed-to-retract-misleading-d%C3%A1il-statements-on-rising

[iv] Chris Arsenault, ‘Only 60 Years of Farming Left If Soil Degradation Continues’, Scientific American, December 5th, 2014, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/only-60-years-of-farming-left-if-soil-degradation-continues/.

[v] Robert Allen, No Global: The people of Ireland versus the multinationals, Pluto Press, Dublin, 2004, p.4

[vi] Untitled, ‘MINISTER CREED MUST ENSURE THAT LIVE EXPORTS TO ALGERIA CONTINUE’, IFA, May 10th, 2020, https://www.ifa.ie/minister-creed-must-ensure-that-live-exports-to-algeria-continue/#.XrgyI2hKg2w

[vii] Irish Freedom Party, ‘Irish Farmers are Strangled by EU Regulations | Frank Shinnock at Irexit Cork’, March 4th, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rp41yqAWkzQ&t=1115s

[viii] Stephen Cadogan, ‘ The origin is green — China is now Ireland’s second most important market for dairy exports’, Irish Examiner, November 15th, 2018, https://www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/farming/the-origin-is-green-china-is-now-irelands-second-most-important-market-for-dairy-exports-885402.html

[ix] Conor Finnerty, ‘Only 1% of Irish farms grow vegetables, the lowest in the EU’, AgriLand, October 22nd, 2016, https://www.agriland.ie/farming-news/only-1-of-irish-farms-grow-vegetables-the-lowest-in-the-eu/

[x] Ibid, Press Release, An Taisce.

[xi] Untitled, ‘Farm 2 Fork and Biodiversity Strategies Hold Firm on Real Targets’, Arc2020, May 20th, 2020, https://www.arc2020.eu/farm-2-fork-and-biodiversity-strategies-hold-firm-on-real-targets/