A poetaster’s tribute to Geoffrey Hill’s The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin (2019).

I heard Sir Geoffrey refer many times in his Oxford lectures (2010-2015) to our current situation as one of ‘plutocratic anarchy’. I suspect that, like many, he was fascinated and frustrated by the oxymoronic sight of ordinary, ‘common’ people persistently voting for, excusing, and admiring those who would subject and exploit them.

People voting against egalitarianism, that sort of thing. People claiming to hate élites and experts, while lauding fatuous celebrities, mendacious politicians and tax-avoiding oligarchs to the skies. What the hell! It’s a job to keep calm, it is. What’s happened to intrinsic value? After such gnosis, what forgiveness?

Hill is, in this Book, much concerned with our chaotic, self-defeating times, but he’s concerned too with cultural instances of last words, late testaments, final goodbyes and deathbed flourishes. The barbarians may be at the ruined gates, but the professor has brought ashore and stored (in his memory) a whole load of good stuff for us. He’s passing it on.

The Book of Baruch by the Gnostic Justin is a Last Supper, a séance, a cénacle, a ‘Scipionic Circle’ (see poem 128), a consistory. Just look who’s been invited, look who’s turned up!

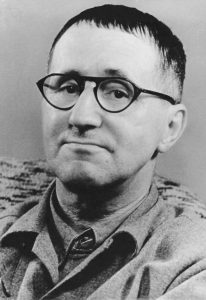

What are they talking about? They can’t be serious. Stuff about ‘fate’ and ‘genius’ and ‘intrinsic value’, and ‘poetry’ and ‘gnosis’ and ‘hierarchy’. And, what’s this, Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) – ‘the Augsburger’ – and his ‘epic theatre’, Brecht who once versified the Communist Manifesto in Lucretian hexameters, and named Brueghel’s Dulle Griet (Mad Meg) a ‘great war painting’ (see 123) – well, ‘it is vital that we | resurrect Brecht’ (124). Christ!

Bertolt Brecht

Final Words?

How to categorise this weird offering, its preposterous form? Is it a biographia literaria (Coleridge)? A tractatus theologico-politicus (Spinoza)? A religio poetae (Coventry Patmore)? A Day-Book of Counsel and Comfort (George Fox)?

Does Hill intend for us to think this is epic theatre? He refers peevishly to W H Auden’s political poem ‘The Orators’ in poem 158: ‘The nearest we get to epic theatre is ‘The Orators’.’

Of this 1932 poem (G.H. was born in 1932), Auden wrote: ‘The central theme of ‘The Orators’ seems to be hero-worship, and we all know what that can lead to politically.’

There’s plenty of hero-worship in The Book of Baruch, plenty of wrestling too with the betrayal of the working class (31), and the embarrassments of the Tory tradition: ‘Tory, to me at this latter day, is both rabble and oligarchy’ (261).

Is Milton’s Paradise Lost epic theatre? I guess so. Milton’s all over the place in The Book of Baruch; amidst the civil war of austerity-and-Brexit, anarchic plutocracy’s generous mess of potage, Hill takes comfort in the compensations of falling towards the grave.

We might more readily expect a Last Will and Testament, I suppose. GH was in his 80s, and whilst he always seems to have written as if he thought he might die tomorrow, well, this is more obviously an apostrophe to those who would survive him. The poem numbered ‘47’ begins, perhaps, with an old man muttering to himself:

If this is going to be your testament best press on with it.

A testament – leaving stuff to someone, testifying to having existed; let’s also remember that GH is masquing himself as one ‘gnostic Justin’, who may understand ‘testament’ more grandly to mean a covenant or new dispensation of some sort, (for those who come after), a scripture, even.

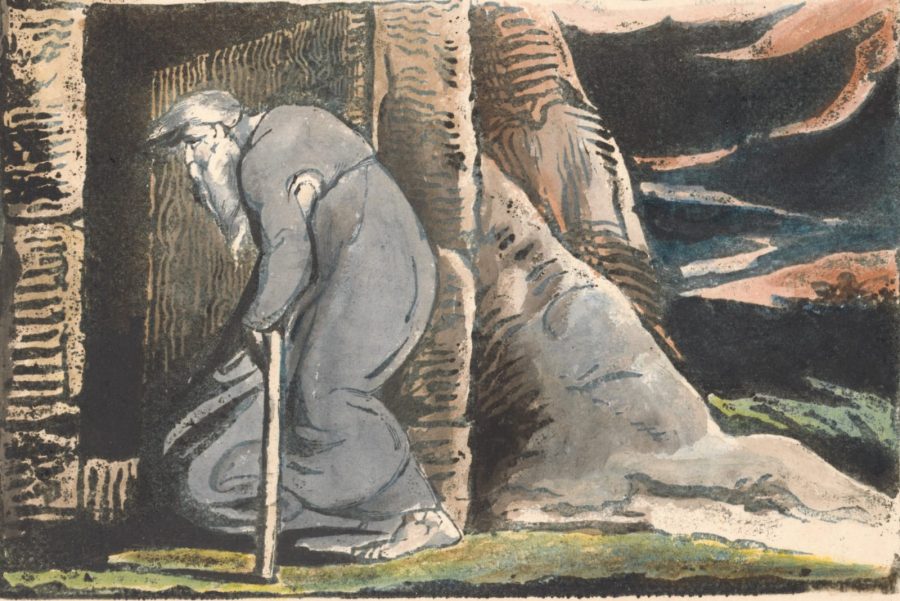

Well, William Blake’s engraving (plate 14) for his America: A Prophecy (1793) is the jacket image, after all. (And Justin appraises that engraving too – see ‘170’: ‘his beard imitates mine in my mock senile portraits’. Sir Geoffrey threatens to get senile on us, but there’s exquisite method in this discombobulation, I suspect).

‘America is an early radiant work if we simply let the illumination bathe us’, a voice declares. I propose that we take time to consider the professor’s last things, and bathe in the illuminations and recriminations that Hill-Justin has to offer?

A Great Gift

So; a generic hybrid. A testament, a covenant, a witness statement, a testimony, a symposium, a reproach, a mockery (Pope’s Dunciad is a lost friend). H’m. I’m only fussing over this because I feel that GH is bequeathing all us ‘poetasters’ – ok, I admit it – a new form to play with.

It is a great gift, and I, for one, am moved to tears. You might say he’s just teasing us with being mock prophetic (as well as mock senile), but that’s ok too, isn’t it? Look at the long lines – they don’t even end at the right hand margin, do they?

Folded back into hanging-indent paragraphs, like a manifesto or, (actually), a stanza from Andre Breton’s ‘Ode to Fourier’ (see 179), or, I should say, looking remarkably like Rimbaud’s lineation in Une Saison en Enfer.

Who’d ‘ve thought it? GH makes something of this source in 167, raving about Rimbaud’s (and David Bomberg’s) part in the invention of ‘modernist poetry’, through an instinctive concurrence, apparently, with the philosopher Berkeley’s redemptive notion ‘that particles are units in the mind’s energy’. (This stuff may need some work doing: you could try D J Greene’s 1953 journal article, ‘Smart, Berkeley, the Scientists and the Poets: A Note on Eighteenth-Century Anti-Newtonianism’.) It’s all part of a thrilling defence of poetry for the 21st century; and look out for Kit Smart (‘no hoodlum’, 28) throughout the poem, and the product of his season in hell, Jubilate Agno.

Not obviously poetry then, but beyond prose, certainly. A 21st century Walt Whitman, for sure, inventorying what’s excitingly referred to (47) as ‘the untenable sanctities of abiding things’. Beyond grasping, out of kilter, implausible, but we do know such things, don’t we?

Certainly, [Listen to me – ‘Certainly’!], an old humanities professor might know a thing or two about what’s worth preserving, what might stay us, what abides, what might redeem the time, dare I say. Is this about redemption, after all, HaShem’s ways to man, and is it now delivered by these here genii and their gnomic achievements?

GH reminds us, for example, of the poet Thomas Nashe’s ‘finest poem thrown away on a dull drama’ – remember that invincible line?

Brightness falls from the air

This from a poem in Nashe’s Summer’s Last Will and Testament (1600), a comedy. Well, if poems can do that…

‘old-fashioned encyclopedic knowledge’

The thing about testament and prophecy, we might remember, is that they’re inevitably political and more or less obviously, satirical, (you can’t get away from Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, the other mockers – Ben Jonson’s ‘On the Famous Voyage’, for instance). Oh, yes – and also theological. Sorry. Well, just think Søren Kierkegaard, if it helps – his many pseudonymous personae – Johannes Climacus, that sort of thing.

Come to think of it, the title of Johannes Climacus’s 1846 work is perfect for GH’s book: Concluding Unscientific Postscript – ‘scrapings and parings of systematic thought . . . divided into bits’, as its epigraph notes. So much I have known, and know, don’t you know? Unbelievable stuff, ‘untenable’, beyond my grasp, inordinate, but something there, let me tell you. I’ve seen things, as the replicant says before expiring in Ridley Scott’s film Blade Runner. Peace be upon him.

It is a great gift, and I, for one, am moved to tears. I’d like to try it too; who knows, my children might be grateful to their poetasting father, when he’s gone? I’m not as old, nor as learned, nor as wise as GH, nor would he have deemed me a poet, but there’s plenty to encourage me here: ‘Poets with old-fashioned encyclopedic knowledge bring good seed to tillage’. (126) And then, later, he writes:

– With always an encyclopedia on which to rest my left

– arm, I do not have to resort overmuch to erm. (256)

Seems to be down to knowledge, then, and not, erm, inspiration (or genius?) Phew! I can do this. The gnostic Jonathan. A gnostic poetaster. Let’s see.

Geoffrey Hill 1932-2016.

Automatism

What else? How to get started each day, overcome the embarrassment and inferiority of the poetaster? Well, I can tell you, GH recommends the practitioners of automatism.

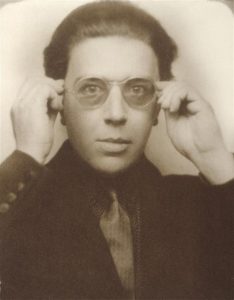

Robert Desnos is our (hu)man – ‘far and away the best of those Surreal men’ (139). I have to look into this. Peter Stockwell’s book The Language of Surrealism is certainly helpful. He writes: ‘in principle anyone could engage in automatic writing’, and refers to a ‘meeting on 25 September 1922 [the year of ‘The Waste Land’, and of Ulysses], in [André] Breton’s studio on the Rue de Fontaine in Paris, at which [René] Crevel, newly arrived from a spiritualist séance, suggested using the same technique for writing.’

Apparently, Robert Desnos was proficient in writing during a ‘self-induced trance-like sleep’, ‘in which striking images were often expressed with dense echoic sound-effects of alliteration, rhyme and punning.’ He wrote, for instance: ‘Mots, êtes-vous des mythes et pareils aux myrtes des morts? [Words, are you myths and similar to the myrtles of the dead?]’ This was published ‘in Littérature in December 1922 . . . under the name Rrose Sélavy (a pun on eros, c’est la vie)”. And these good mots duly make their appearance in Baruch – check number 139. Is this the discombobulating method?

There has to be something in this for the gnostic Justin, right? I can’t prove this – (Go-ogle doesn’t know, for heaven’s sake – how agnostic is that?) – but I think the line quoted in poem 73 of this Book of Baruch: ‘To run on empty is to achieve a sort of hallucinatory abundance and clarity’ – I think this must be a translation of something in André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism (1924), and that Breton is the ‘Parnassian and … sassy man’ also mentioned there, (not Hopkins, who is above that, as we know).

André Breton in 1924.

The paradox, the oxymoron – they’re pretty surreal, aren’t they? GH always had plenty of time for the paradox, the oxymoron; and the cryptogram too, I’d say; all is surreal in such verbal tourbillions (Robert Graves’ brave word; see ‘On Portents’, and appraised by GH in one of his lectures). And – just in passing – there’s plenty of focus in Baruch on ‘codes’ – ‘the codes from London were always that absurd’ (89) – and the weird poetic lines/codes in Jean Cocteau’s film Orphée (‘a cultural film of established acclaim’ (139)), and – would you believe it? – Alan Turing’s turned up (227).

There is something in this. Let’s remember, those codes did mean something, (to those in the know, to those in the Résistance (89) or the Widerstand (255), for instance, God bless ‘em). People do solve cryptograms, don’t they? Poetasters are with the resistance too, right? Codes for a consistory. Like Polari, or Yiddish.

But how much cryptic and recondite erudition can the nation – those to whom we bequeath all this – tolerate? (See 163) The poetaster will do well to remember how her work may be received; words of warning: ‘Poem as inaccurate | prism inaccurately decoded; progressively derided; making honest | decent people appear stupid; all the pretence of a séance’ (163).

But take heart; let’s not forget that final mystery about which the mystics advise, and via, apparently, this same automatic writing (see Evelyn Underhill’s Mysticism) – look at this in poem 40, our professor musing on ‘intrinsic value’ and John Donne’s final writings: ‘our grandest poetics | perform their mystic dance of savagely disputed provenance.’

Hallelujah. Hill-Justin notes, approvingly, ‘Rouault’s mystical aggressive passivity.’ And has a mystical experience of his own, with ‘[d]ense holly trees’ (221). This is, after all, ‘’Geoff’s Mystery Tour’, perilous self-entertainment that would have | delighted my Aunt Nell, the bright one of our family.’ (178) This delights me: ‘All the mysterium of God is in the measure of time.’ (183) Who knows otherwise?

Form and Process

So much for form and process? Worth pausing here; because I want to say that (what used to be called) the content of this mock-prophecy is absolutely fascinating too, no doubt about it, I’m ashamed to admit. So I’ll come back later, if you don’t mind, to this thing about form and genre and provenance, this ‘All Souls’ Night’ (Yeats) summoning to a final showdown, a last reckoning.

A little bit about the content, even though the Professor insisted this is of no interest if it hasn’t got ‘technic’, (also Yeats, (and Ezra Pound)). But we’ve established the technic is automatism, isn’t it, the subjective-made-objective, the mask which is self-portrait, the sensibility-register. The anti-lyric, too. See 182: ‘The form I choose is monologue though with frequent episodes of multi- | voiced fugue.’

Firstly, if you’re the sort of person who likes to hear, say, Sir Geoffrey Hill choose his favourite bits of music, (he was once on Radio 3’s Private Passions, where the ‘Coventry Carol’ played alongside Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Star-spangled Banner’), well, this will be a revelation, (as prophecies are supposed to be, no?)

Here – this is important to say – you have to simultaneously hear, as counterpoint to various musical miracles, the bells in Wren’s churches crashing to the ground during the Blitz. This prophecy is ‘loud with falling bell-chambers’ (10), ‘bells, a last | cascade of thrashing, mangled squeals’ (36), ‘bells falling and bawling’ (2); and ‘the toppling creel of half- | melted bell-metal’ provides a great metaphor for automatic writing and this whole book: ‘astonishing collocations of syntax and semiotics’ (36). Hill-Justin listens, too, hoping to “cough up the phlegm of a poem”, to

The mingled throps and thrangs of bell-ropes and bell metal, mangled and

_ muffled songs, when you stand beneath the bell chamber, hearing the

_ ropes grunt and clamber. (72)

We might recall the opening lines of Yeats’ séance poem, ‘All Souls’ Night: Epilogue to ‘A Vision’’:

Midnight has come, and the great Christ Church Bell

And many a lesser bell sound through the room;

And it is All Souls’ Night

The Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, designed by Christopher Wren.

I think it’s midnight for GH too, and HaShem’s in the tomb, and Tennyson’s ‘Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky’ is a distant memory, (lacking some ‘obduracy of the mind’s address’, apparently (69)). When Hill-Justin tried to compose music himself, he informs us, he failed: ‘My piano compositions failed because I could not compose a convincing | ground bass’ (249). He succeeds here, with Wren’s crashing bells.

We should remember GH didn’t want to be a poet, after all:

I would have prayed to excel in mathematics and music if I had prayed at all;

_ envying Wren and the musicians of the Chapel Royal; passacaglias and

_ Purcell; for that is where the mind stands to itself, albeit in hell. (25)

Well, look – listen! – the music of Purcell does seem to come out on top here. (When GH was invited by The Economist to read his Clavics and work-in-progress at the Purcell Room on the South Bank in 2011 – ‘What! Six daybooks, already?’ we all declared. (Actually, seven now.) – GH closed proceedings with the most menacing and atoning rendition of Hopkins’ sonnet ‘Henry Purcell’ you could ever dread to hear.) GH seems to agree with what Hopkins says of Purcell:

The poet wishes well to the divine genius of Purcell and praises him

that, whereas other musicians have given utterance to the moods of

man’s mind, he has, beyond that, uttered in notes the very make and

species of man as created both in him and in all men generally.

Wow! (Plenty of derogatory stuff about ‘moods’ as the domain of mere poetasting in Baruch, be warned.)

And Hopkins is a key presence at the table – this cénacle – throughout. In 176 Hopkins and Purcell are linked via Purcell’s ability to create ‘sprung rhythm | two centuries before ‘That Nature is a Heraclitean fire’ which its | rediscoverer – a devout Purcell admirer – felt duty bound to keep | hidden lest he should bring notoriety upon the Society in which you do | as you are bidden.’

Odes and Welcome Songs

Let’s see which bits of Purcell are playing at the Feast, on ‘the wind-up gramophone’ (137). Well, it seems to be his Odes and Welcome Songs (185; 187; 188), and this is what Hill-Justin says of them: ‘these ‘welcome songs’ feature a benign vision for the future of the | kingdom in accordance with divine nature’ (188).

He goes on to express extraordinary gratitude and estimation (189): ‘Tell him his saddest | music well-betides us, elides all but our last, worst fears.’ Plenty of compensations, then, even after a referendum and all history’s idiot repetitions.

So much for content? O, but look out for, nevertheless, Schubert’s Quintet (70; 253), Handel’s Saul (79) – ‘how profound the accessible can be, | given mastery” – Thirties jazz – “accurate music appropriate to heaven” (36) – Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols (130), ‘L’hymne de l’Union Européenne’ (140), symphony number 9 by Malcolm Arnold – ‘old Malc’ – “that final untri- | umphing lento of twenty-odd minutes”, “its near subliminal song” (197), and Ralph Vaughan Williams:

I bless the marvellous

‘Five Mystical Songs’: although strong music cannot

_ even begin to mend wrongs, it is, in some way I wish I could well relate,

_ analogous to the Pentecostal tongues. (85)

Ok. So – poetry – this poetry – aspires to the condition of music, yes? Well, I’m not sure about that with Hill-Justin, after all. Set down this, set down this: ‘Not | music. Hebrew. Poetry aspires | to the condition of Hebrew.’

Of course! Now we’re talking. This naughty apophthegm is ripped from Hill’s 2000 prophecy, Speech! Speech! (poem 20). Such wisdom bears contemplation. (Well, I’m reading Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century as back-up).

And I was always told the three archetypes of the human condition to be Faust, Don Juan and Ahasuerus, don’t you know. [Whilst we’re here, Wikipedia keeps us informed that Kant himself refers to the legendary Ahasuerus, wandering Jew, in his The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God. I’m reminded of Hill’s long-time interest in Peirce’s ‘A Neglected Argument for the Reality of God’. – Sorry – am I going into séance mode?] And what about Lear as archetype too (God’s spy)? What about Falstaff (God’s clown)? Our prophet is all these.)

Hill-Justin – the poet-prophet – as Ahasuerus. Exiled, unhoused Adam. Well, this did preoccupy John Milton at the end of all his hopes and dreams. Where did it all go wrong? And Milton’s all over The Book of Baruch, as I say. ‘Latterly, led by the hand in his good grey coat, a blind good looker, looking like | a Quaker.’ (18)

Supremely non-conformist, speaking truth to power, aficionado of peace. And a reader – don’t you know – of the Hebrew scriptures. Geoffrey Hill, Hebraist, (there was a quotation in Hebrew for The Triumph of Love (1998), wasn’t there?) He refers mysteriously in 96 to ‘the | inexorable semitic-semantic code.’ Is this that ‘God’s grammar’ thing, again; isn’t that from John Donne? Still, the still, small voice.

John Milton 1608-1674

Love Supreme

The gnostic Justin, we think, was ‘Jewish-Christian’, and, excitingly, considered a heretic by Hippolytus, (third century). And look at this:

But because I am not a Jew I desire to know all that was said when, once a year,

__ the high priest convened in holy fear with the Ark of God.

Hill’s naughtiness and perspicacity, his agile-mindedness and contrariness and impetuosity all remind me, at least, of the Hebrew prophets. It’s a familiarity with HaShem (her omniscience and inordinacy), a longing to hear HaShem’s voice (in the gathered silence of this Quakerly meeting), which makes Hill’s encyclopaedic mind, too, into a psaltery of praise and vexation and vexatiousness. Isn’t this the Hebraic mindset? Forgive me.

Hill repeats this sense, actually, of exclusion from, what, the chosen race? In 216: ‘I am not a Jew though I married one; and I subscribe to their iron scorn.’

Jewish cultural illuminati are prominent and are revered. Besides the anonymous authors of the Gnostic Bible (40) and The Book of Job (86), there’s Simone Weil, of course, Robert Desnos (very much so), Len Rosoman and his commentary on the epicentral Mad Meg painting (is it a pogrom?) by Brueghel; David Bomberg too, Celan, Tzara, Gershom Scholem (think his Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (1941)), the Mandelstams, Gillian Rose (quoting from his late friend’s Judaism and Modernity, wouldn’t you know; must read this), Sandy Goehr (his co-eval), even Leopold Bloom; the Jewish century, I’m convinced.

We see ‘Willy Brandt at the | Ghetto memorial’ (77), consider ‘the topic of Jews and usury’ (186), never forgetting strains of antisemitism in ‘my grievous heroes’ (186; 111; 177). And a strange and riddling identification: ‘Ich bin Dreyfus, an old man who walks with a cane, thus – ‘ (189). If poetry aspires to the condition of Hebrew, then I suppose the poet’s task is both to resist and to aspire to scriptural authority for herself. A bit much for a poetaster, truth be told.

Anacoluthon!, as decency demands. Yes, even Love Supreme has to come to an end. Let me finish, please. We’ve got the Hebraic mindset then, the surrealist automatism and discombobulation, the musical passacaglia – and we’ve also got pained awareness of the betrayal of the working class (and the European mindset, bien sûr), the death of intrinsic value (O, no it’s not!), there’s Hill’s gnostic ‘back garden apple’, his parents’ suffering and his childhood, poet-soldiers and – pilots, (Eric Ravilious, d. 1942 (242)), war photography (Mathew Brady (247)), divination (everywhere), and Coke (1552-1634) and Grotius (1583-1645) laying the foundations for international law, as all great poets do, too. Mind you, let’s be clear:

The waters recede: neither covenant nor creed. (236)

This great prose poem, divine table-talk, is endless. You can’t stop loving it. As Ezra Pound wrote of Wyndham Lewis’s work in 1917 on illustrations for Timon of Athens, (and quoted in Baruch, 229), we hear everywhere the prophetic “fury of intelligence baffled and inspired by circumjacent stupidity.” But this fury is never unmixed with “ ‘summer’s sovereign good’” (from, is it, the last poem Hopkins wrote?) and (though not “irrefutable”) “evidence of cosmic cadence” (256). How GH loved this all, all this wisdom, all this folly.

Love you, Professor. Lead the way.

Intrinsic value that I care about is as tenuous and wiry as a bit of great verse. (163)

It is a great gift, and I, for one, am moved to tears.