It’s only a day’s walk north from Sana’a to Al Madid, in the province of Neham, so I said, ‘In Al Madid, God willing, surely we’ll find what you seek.’

Wearing a cuffia, the small man eyed me with a detached superiority while I thought to myself, ‘How fortunate he is to have me. With someone else, he could find himself in a perilous state, Yemen being Yemen. And Yemenis being Yemenis, they may not tolerate his lofty air.’ However, being a humble Yahud I chose to ignore it. We were on foot, heading toward the Mareb and the mountains. It was still spring.

I’d been told the bare minimum by the small man, Baahir Jalali, and in truth had no right to know more. But curiosity is a beast all its own, and a beast must be fed. My countless questions kept falling flat though, so I ceased my futile efforts. If he wanted to speak, fine. If not, so be it.

Poverty in the countryside is such that we traveled with nothing of value. Not even food. Without provisions, we trusted in the Jews of Al Madid. I carried a letter of introduction from Moshe Alkarah, a well-to-do merchant based in Eden. He knew Baahir Jalali and had recommended me, Al Fathihi, to act as his guide. Addressed to the Rabbi of Sana’a and other Rabbis in other towns, the papers I possessed requested we be looked after and promised reimbursement for any out-of-pocket expenses, in due course.

The barren mountains stretched ahead and as we walked, endless dust swirled at our feet. My eyes roved, seeking the few plants that found strength to sprout and cling amongst the rocks, existing on thin air and hope. Were we not doing the same ourselves? The hours crawled by and Baahir Jalali was getting tired, because in spite of his steely gaze his body was made of something softer. When we came to the outskirts of Al Mawqiri, a small village not far from Al Batah, both of us were thirsty as two empty humps on a camel.

In the distance, I glimpsed a girl tending goats. Baahir Jalali rested his bones while I went for water. About thirteen and completely covered, only her tired eyes and chapped lips were exposed. Glad for the interruption, she offered me a leather pouch spilling water and asked a thousand questions. I answered a few, pouring the precious clear liquid for my friend into her clay dish, which I swore to return. Picking some plants, she pressed them into my hand and said ‘Eat.’ I trusted doing this would energize us and ease our walk. Baahir Jalali was dozing when I returned, but quickly revived to say water had never tasted so good. Chewing her herbs, we stretched our legs and massaged the soles of our feet.

The sun’s movement across the sky meant we must carry on if we were to reach Al Madid before nightfall. At last, perhaps bored by his own thoughts, the small man spoke, ‘Have you ever been to Lahaj?’ I’d never had that pleasure, but asked if it was true they sent water to Eden? Baahir smiled, ‘One hundred camels carry bags of water every day!’ he boasted triumphantly. ‘Lahaj is beautiful, its palm trees plentiful and their dates so sweet.’ He spoke of big juicy melons, then with probing eyes, asked if I knew the Sultan of Lahaj: ‘I’ve only heard of him,’ I answered in all modesty. Baahir Jalali laughed with delight and seemed slightly relieved.

‘It sounds heavenly. All those rivers and green fields.’

‘Oh yes! It is most certainly heaven on earth!’ sighed Baahir Jalali then he fell silent for a while. Waiting. Debating in his mind. He weighed it carefully before casually mentioning his grandfather had lived in Lahaj.

‘So why do you not live there?’ I asked.

‘Long story,’ said Baahir Jalali with a smirk.

‘This road is long. Your story will not last the length of it.’ But Baahir Jalali grew quiet.

I gave up on getting anything out of him, but only then, of course, he answered. Baahir was not born in Lahaj, because his father left there to look for a key.

‘He left Lahaj only to locate a single key? This key must be quite unique.’ Baahir Jalali smiled and left my unanswered question dangling there between us.

Our walk resumed, we both kicking stones and me trying to make some sense of this mysterious man. Suspense was clearly his currency, and I had a strong suspicion he was toying with me. Asked a direct question, he didn’t divulge, but when I relented, he tendered the most granular detail. Determined to deprive him the pleasure of depriving me the answer, we walked on.

The wilderness pressed in from all sides, leaving us to stare at the rugged mountains straight ahead. Baahir Jalali retreated back behind his personal well of thoughts, his bushy brows shaded eyes further darkened by contemplation. It was not in my nature to sustain a vexation with the taunts of this haughty man and slow as a snake twisting up a tree, my curiosity reawakened, tickling my mind as we passed the place called Jabal Dhimarmar. The springtime sun slid further down in the sky, and yet still it sliced our backs like a hot sword.

‘Tell me, what is the importance of that key?’ I felt compelled to ask. Baahir Jalali jumped, startled out of a somnambulant stroll, and from his twinkling eyes, a smile melted across his face to form deep dimples in his cheeks and softening his grimace, revealed a row of teeth, perfect as pearls.

‘I’ll say more than I intended, but only if you promise not to say one word to a single soul.’

Vaguely intrigued before, I must admit he had me eating out of his hand.

‘And be warned,’ he continued, ‘possession of a secret can put you in danger.’

At this, I laughed, ‘Surely, you’re not serious?’

‘I am serious. What is a secret worth without any risk?’ His glare mixed gravity with bemusement at how my curiosity, like a flame kindled, now leapt out of control. Patting me on the shoulder, Baahir Jalali promised knowledge that would hold me hostage to him and his secret. Unhurried, he inquired ‘How long until we reach Al Madid?’

I saw the sun low in the west, ready to slip behind that mountain and said surely we still had hours to go.

Baahir Jalali sighed, ‘We’ve eaten nothing, and I’d settle for a simple cup of coffee.’ ‘Coffee.’ What a word. It sent my head spinning, with a longing that weakened me and I had to agree, ‘Coffee, would be good, indeed.’

‘I’ll finish telling you that story later.’ He said, ‘Now all I can think of is food.’

‘No, please talk,’ I pleaded. ‘Say anything to make us forget our hunger.’ So he spoke.

Baahir Jalali was not born in Lahaj, but his father was Shafiki, son of the Sultan. I did not doubt him for a moment but began to believe that the road we were on had no end. By some miracle the soft hills parted, we rounded a corner and stumbled upon a small holding. In the midst of its sand and gravel, stood several coffee trees, their leaves a lustrous green.

An old man squatted in the dirt, just off the trail, staring into the empty distance, then greeted us, ‘Salam Aleikum.’

‘Is this your land?’ I asked.

‘Why else would I be here?’ he answered in a bored tone of voice locals reserve for travelers.

‘Please could we have some coffee?’ I ventured. He was weather-beaten but wiry as a young goat, and stood up on his feet to bellow, ‘Latifah, bring coffee. Now!’

A stunning girl of seventeen brought us three glasses of coffee on a woven tassey, and to our unfettered delight, put down a plate of dates! Squatting alongside the old man with all the willpower we possessed, we ate the dates at his measured pace. ‘Your daughter?’ I asked, politely sipping her spiced coffee.

‘God, no! She is my new wife,’ he said, swelling with pride.

Satiated by strong coffee and sweet dates, the old man asked, ‘What business brings you here?’ Baahir Jalali looked to me, but I hesitated to speak, not confident I’d been informed of the complete story, myself. Quickly it became clear Baahir Jalali was leaving it all up to me.

I said to Sa’idi, that was his name, we were collecting stories about an ancient queen. She was called Sheba, and once ruled these lands. Did he know any stories? Old Sa’idi waved his hands as if to say, ‘Waste of time. Centuries ago. Forgotten!’ ‘But there must be some stories passed down? Generations of people tell their children old tales.’ His eyes were open, but Old Sa’idi sank into a sort of sleep.

The lovely Latifah brought him a nargila pipe and absentmindedly, he stuck it between his lips without exiting his trance.

‘Where are you from?’ Alert now and abruptly he turned to interrogate Baahir Jalali. Locals regularly treated foreigners with suspicion. For this reason, Baahir Jalali reclaimed his roots. ‘Lahaj. And Al Fatihi, here, is from Sana’a.’

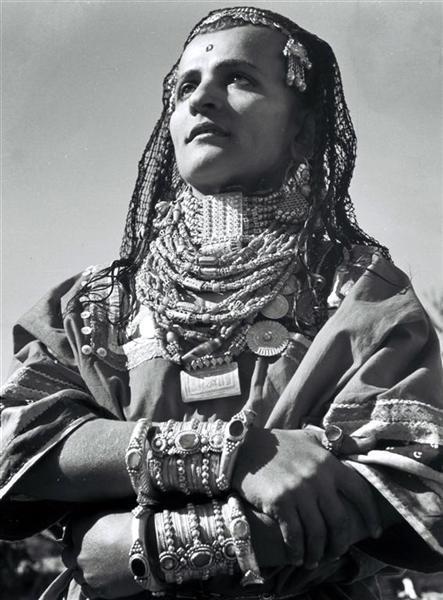

The old man sank back on his soles, ‘I seem to recall something about a man from Lahaj. Must have been sixty years ago…’ Old Sa’idi adjusted his cuffia and scratching the back of his neck, he said, ‘Yes, I was about five years old when a fancy young man from Lahaj came through here on his way to Al Madid. Found out later he was the son of the Sultan. It’s been so long but I’ll never forget the gorgeous young girl he had with him. As if it were yesterday, I still see those eyes of hers, green as basil. The man, Shafiki, claimed she was his wife and kept calling her Cat. And by God, she did resemble a cat with those enormous green eyes. The rest, of course, was always covered, but once I was alone with her. Lifting her veil, she held my face in her elegant hands and said to me, ‘My child, one of these days, one of my own will come for you and yours.’ When I think of it now, she was merely a child herself!’

‘So why did they come to your place?’ asked Baahir Jalali and Sa’idi scratched his head.

‘They were looking for a tablet. One of the old stone ones they say go back to the Sabaean period, with writings on them. We only have one here. Salam Al Saudi brought it back. From Al Narjan.’

‘The tablet has an inscription?’ Baahir Jalali vibrated with excitement and making myself small, I watched how hotly he asked Old Sa’idi, ‘Did the local people reveal the tablet?’

‘They didn’t dare. As you know, bad luck will be unleashed if these tablets fall into wrong hands. Cat claimed it rightly belonged to her, but the people said she would find many more tablets in the south. They asked her why she must have Salam Al Saudi’s slab? She insisted she was searching for a particular stone. Something about the writing.’

‘What was inscribed?’ I almost whispered.

Old Sa’idi shook his head, ‘Who knows? It’s a long forgotten language.’

‘What would a woman want with that tablet?’ asked Baahir Jalali, on tenterhooks, stuffing each of his trembling hands into the opposite sleeve of his robe. Sa’idi shrugged his shoulders. ‘She didn’t get it. They buried it so well under the floor of Salam Al Saudi’s house. Back then he was the last of his line. And now, he’s long dead.’ Sa’idi sucked deeply on his pipe which made the water gurgle.

We three sat quietly, thinking of Shafiki, Cat and their tablet. Jalali calmed himself and I said,

‘It’s a good story.’

‘Yes, yes, it’s a great story!’ agreed Baahir Jalali a tad too enthusiastically.

‘So Salam Al Saudi’s house, is it in ruins?’ I ventured.

‘Yes. But everyone knows where it was. It was the last house at the end, where the Mareb road leads in the direction of Bab Al Yahud.’

Like a jackass who can’t restrain from running, Baahir Jalali was dying to depart out the door. But I sat for more chitchat with Sa’idi, and thanking him for his hospitality, we left hopeful to reach Al Madid before dark.

It was cool and nearly night when we arrived to a pleasant dinner at Yahya Mansoor’s house, modest fare laid before us made tasty by the undeniable goodness of our host. We mentioned an early morning meeting with the blacksmith would make us late for breakfast. Mansoor showed polite interest in our appointment, but Baahir Jalali deferred going into detail until the following day. And before anyone, including the sun, was up, we set out.

With only a sliver of moon to light our way, we found the ruined house of long dead Salam Al Saudi. We knew it by the Star of David hung high in a niche on the wall, just where Old Sa’idi had described it would be. Rubble piled high made our mission seem impossible, but Baahir Jilali began pulling large stone slabs and expected me to come to his aid. My hands are more accustomed to pen and paper, so I said ‘We’ll not get far like this. Two people in the dark.’ He eyed me in a way that could only mean, ‘dig or I don’t pay.’

I shifted smaller stones, and after two tedious hours, it was daybreak and Baahir Jalali began to agree with me. We needed help, but first it was time for breakfast. Sweet words indeed! We walked back and Yahya Mansoor’s wife had prepared a simple meal with as much coffee as we desired. Mansoor was too busy to hear about the blacksmith, but on his way out said, ‘I’ll be seeing him later, myself!’

‘Better go see that blacksmith,’ grumbled Baahir Jalali, the moment Mansoor left the room.

‘Because?’

‘Because, we said we would and Mansoor may discover we lied.’ He was impatient with me.

‘But what business have we with the blacksmith?’ I asked.

‘You’ll think of something!’ he snapped.

‘More urgently, who will help us dig in the ruins for the tablet? Shall we trust Sa’idi?’

‘Let us ponder that on the way to the blacksmith,’ answered Baahir Jalali. And on our way to see Sa’idi we pondered more. Could we get Old Sa’idi’s help without the locals learning what we’re after?

‘We’ll give him something.’ Concluded Baahir Jalali.

‘But what have we to give?’ I simpered.

‘One always has something to give…’ What was in Baahir Jalali’s devious mind? Close to Sa’idi’s place Baahir Jalali stopped and said. ‘I must say something before we see Old Sa’idi. As you may have gathered by now, Cat is my mother, Safia.’

Safia, was the daughter of an Italian, Doctor Montalbano, who lived in Eden. When the Sultan fell ill, his doctors, unable to cure him, called the Italian to Lahaj. Montalbano’s wife was originally from Lahaj and happily accompanied her husband back to her hometown. The couple brought along their adorable daughter Safia, who had just turned twelve.

During his treatment, the Sultan took a particular shine to this green-eyed girl in his palace, as did she for his statuette, a cat cut from stone. It sat on a windowsill of the Sultan’s private chamber, and one day lifting the statue, Safia found a key fitted into the base of it. Since nobody was looking, into her pocket slipped the key.

‘My father told me, the moment she held that key in her hand, she knew it was meant to be hers and hers alone.’ Baahir Jalali repeated like a mantra.

‘I don’t follow,’ I mumbled mostly to myself before he added…

‘My father never explained this preternatural episode to my satisfaction. Perhaps he didn’t understand it himself? He did say, there are some things in life we are not meant to understand and the wisest of us would not try.’

For safekeeping, Safia stowed the key deep in the stuffing of a doll and sewn up tight, returned with it to Eden. Months passed before the complacent Sultan discovered his key missing and with that, all hell broke loose. No one really remembered the significance of the key, dutifully passed down from father to son, for generations. Long before the people of Lahaj were who they are today, the key was always there. When the imams and aristocracy had not yet converted to Judaism, already they believed the key to be essential, a lucky charm. Its absence made the superstitious Sultan and his people uneasy. Its loss could bring permanent misfortune on the tribe. This made it imperative to locate the key, and bring it back where it belonged.

The Sultan trusted his youngest son, his favourite, to resolve this affair. Shafiki was a smart young man, and assembled the whole tribe. Investigating each great family, he deduced only an outsider could have taken the key. Who strolled through palace gates and gardens, right in to the Sultan’s inner sanctum? His father’s concubines. So Shafiki conducted careful interrogations to satisfy himself of their ignorant bliss. Previously unaware of the key, word of its disappearance had even reached their exquisite ears and all over Lahaj, hushed whispers hung in the air.

Good citizens began sulking in anticipation of evil genies unleashed on the world. Shafiki was determined to calm them. He had a theory and so set out to see Doctor Montalbano in Eden. Montalbano received him cordially. Shafiki avoided any discussion about the key, describing the purpose of the visit as an expression of the Sultan’s ongoing gratitude. The doctor dismissed the idea of yet more lavish gifts, insisting Shafiki remain rather than rushing his return to Lahaj.

During the days that followed, Shafiki noticed Safia’s strange attachment to her doll. Wisely, he surmised she was beyond the age of clutching such a toy but not too young to be the thief. ‘What is it about this doll that makes you cling to it so?’ Safia’s eyes filled with defiance as she bit her lips in determination that not one word of confession would spill from them.

Shafiki demanded ‘Give it back. It’s not yours. You know what they do to thieves, don’t you? They cut off the hand that stole!’ He glared fiercely and after an eternity spent staring in to her eyes so green, found himself hopelessly ensnared. Shafiki had fallen in love with Safia.

Returning to Lahaj, Shafiki informed his father that he had located the key. The Sultan demanded details, but instead Shafiki reminded him, “Did you not stress the key should remain in good hands, with the people of Lahaj? The Sultan admitted that was true. Then you must allow me to marry Doctor Montalbano’s daughter.’

This statement confounded the Sultan, who saw no connection between the missing key and his son’s future. Shafiki went on to say, ‘I’ve been to see Montalbano in Eden and his beautiful Safia resembles that cat statue in your private chamber.’ The Sultan’s furrowed face brightened as finally he followed his favorite son’s plan.

Doctor Montalbano was taken aback when Shafiki asked his daughter’s hand in marriage and his wife said her little girl was too young. Shafiki was willing to wait years for kids, but about the ceremony he insisted, ‘I must marry her now.’ The doctor could only consult with Safia, explaining, ‘I’m European and in Europe we let our daughters decide for themselves.’

So besotted was Shafiki by Safia, he endured the doctor’s delays and Italian egalitarianism. Montalbano’s final condition stipulated that instead of his daughter living with her in-laws in Lahaj, he preferred Shafiki stay in Eden to help in his medical practice. ‘I always wanted a son. I’ll teach you medicine.’ This seemed to Shafiki a last straw. His life was in Lahaj and the great outdoors.

He spent his days on horseback, supervising the farming activities that sustained his tribe. Riding alongside the Sultan amongst palm trees, disgruntled Shafiki consulted his father regarding this complicated marriage. ‘I find it a splendid idea,’ said the Sultan. ‘Lahaj is not far from Eden. You’ll visit often.’

I’d been standing around in the heat, listening to Baahir Jalali’s story when all of a sudden he looked up, appalled, ‘I’ve said too much! You know quite enough already. Sai’di’s young wife is his weakest link. Just let me do the talking and don’t try to help.’

God bless us and save us, I thought to myself. Did I ever meet a more conceited man? But he’s paying the bills, so I will obey.

Nearing Old Saidi”s place, we found him right where we’d left him. If anyone told me he’d slept squatting on his soles like that, looking at the mountains, I would’ve believed them. Sa’idi saw us and didn’t seem surprised in the least. ‘Salam Alaikum,’ We replied in kind.

‘Did you find the house?’ His question clarified just how transparent we appeared.

To his credit, Baahir Jalali was quick to recover, seeing no point in beating about the bush.

‘Yes, we did,’ he replied. ‘Shame the place is in ruins.’ But Sa’idi was not sentimental. ‘And the tablet?’ His knowing eyes found me and he smiled. ‘Many come searching but none find,’ was his answer to the question we had not asked. He sucked deeply on his pipe, and the water it contained gurgling through the filter was the only noise we heard until he set it down.

Old Sa’idi jumped again like a young goat, calling lovely Latifah who brought us black spicy coffee. We sat sipping and Sa’idi said, ‘I’m an old man.’

That is fairly obvious, I thought to myself.

‘And I have a young wife,’ he continued.

What was he driving at? I kept quiet, looking at Baahir Jalali politely nod.

‘I would like to live longer for Latifah,’ said the old man whose eyes began to well up. Baahir Jalali stopped nodding to stare harshly at Old Sa’idi when he said ‘and be young again.’ Returning Baahir Jalali’s judgemental stare he demanded, ‘What will you do for me? I want more time.’

After some silence Sa’idi said with utmost confidence, ‘I presume you possess the key.’

Baahir Jalali croaked, ‘What makes you say such a thing?’

‘Because Cat was your mother.’

Beneath his sallow skin, Baahir Jalali blushed.

‘Don’t have her green eyes, but you’re certainly Safia’s son.’

‘What is the key for?’ I blurted, carried away by my confusion in the moment until Old Sa’idi’s eyes darted disdain in my direction. ‘He didn’t tell you?’ I was starting to feel stupid.

“First, find the tablet,” Old Sa’idi advised as if the entire story were written there and Baahir Jalali wore a silly smile until Sa’idi said, ‘The Sultan, Shafiki, Cat. All dead now.’

‘Yes.’

Sa’idi sucked his pipe, then offered with some finality,

‘So we’ll do a deal.’

Old Sa’idi wasn’t in a rush. It seems old men never are, despite the short span that stretches ahead of them. No, he meandered like a slow stream licks every stone with love.

‘I don’t pray for riches or immortality. All I ask is another forty years. No more. I’ve learned too late contentment in a woman’s company.’

You could have fooled me, I thought. Latifah seemed more a servant than a companion.

Baahir Jalali was not laughing, but said ‘What have you got?’

‘I’ve got the tablet,’ said Sa’idi, resolute.

Jalali jumped up glaring, ‘You said it was in the ruins!’

‘I lied,’ said Sa’idi.

Jalali paced up and down the road. Muttering to himself, he kicked the dust, then shouted ‘It’s not yours!’

‘It’s not yours either,’ said Sa’idi, unfazed.

‘How do you know you have the right tablet?’ growled Baahir Jalali.

‘If the key fits.’

Baahir Jalali must have had a better idea because now he was positively beaming.

‘Ok,’ he said. ‘You’ve stated your wish. To be young again and live for another forty years? Am I correct?’ Sa’idi bowed, but his eyes remained opaque.

‘Shall we dine to conclude our deal?’ asked Baahir Jalali. ‘I’m famished!’ The old man was also ravenous. Making love to Latifah, even if only imagined, produced in him a vigorous appetite. At last we spoke of something I understood. Together we approached Sa’idi’s home. In the Yemeni style, the tall building was constructed of red mud and decorated with white filigree around the windows. We entered the dewan where Latifah and an older woman were preparing a minor feast. Gesturing to the older woman baking fresh pita bread in a hot charcoal oven, Sa’idi introduced her as, ‘My first wife.’

Both women served zehook, hilbe and a fragrant chicken soup. There was rice with shredded carrot and also baba ghanouj. We tucked in like there was no tomorrow and finished the meal with coffee. The older wife brought a nargila which we then smoked in silence. The water in the pipe was still gurgling when Sa’idi left the room.

Soon he returned with a heavy stone slab wrapped in soft white cotton. Laying the tablet down on a low table, Sa’idi sat now ignorant as I. It was Baahir Jalali who recited the strange words carved on the stone, and me dying to know, ‘So what does it say?’

I detected a slight tremor in the hands of Baahir Jilali as he translated, ‘The green eyed Cat, you and yours will be obeyed,’ he said. Sa’idi bowed his head, but Baahir Jallali mulled over this, mumbling ‘You and yours.’

‘What does that mean?’ I asked.

Baahir Jalali shot me a look that said ‘Silence.’ If Sai’idi noticed anything, he didn’t let on, standing still as a stone statue, himself. Impatient, I watched the key in Baahir Jalali’s hand, move in slow motion, and I was suspicious. Did he have something devious in mind ? Sai’idi, as usual, seemed less hurried than I. Baahir Jalali, finally ready, flipped the tablet over. There was a point carved in to the stone, where he was able to insert the key. Just as he was about to turn the key, Old Sa’idi’s voice came out of him, as if from a cavern made of the same stone. ‘Don’t forget I’m yours.’

Baahir Jallali retracted his hand. ‘What are you saying?’ He asked.

‘The Cat blessed me, and don’t you forget it! She made me one of you! I couldn’t comprehend what she said at the time, but later I saw the tablet and understood everything,’ said Sa’idi.

The old man motioned for Baahir Jalali to go ahead and turn the key. At a loss, he did just that. The tablet’s tiny door sprang open to reveal a compartment. Its box-like interior was beautifully inlaid with gold, but otherwise quite empty. Staring in to it, we saw nothing but heard what Baahir Jalali said was the sound of the sea. Sa’idi and I had never seen nor heard the sea in all our lives. So over the deafening roar Baahir Jalali described to us what waves looked like and in our imagination we watched them crash on the shore.

To our astonishment, a golden bird materialised inside the box. But before we could catch it, the bird flew away into the blue sky, taking the lining of the box with it. All the gold was gone. And when Baahir Jalali closed the little door, we saw even the key had vanished.

Stupefied, we stared at each other and then at Sa’idi. In his place was a much younger man with a big open smile full of strong white teeth. I was speechless but Baahir Jallali shouted,

‘Our wish came true!’ I could see that Sa’idi got his wish, but what did Baahir Jalali get?

He hugged me, singing ‘All is good! My son is healed! I saved my son!’

‘You have a son? Your son is saved? How do you know?’

“I just know,” said Baahir Jalali. “I thought Sa’idi would spoil it all but it still worked.”

Mystified by these events, I was feeling a little left behind. That is until Baahir Jallali took my face in his hands and said, ‘It is only for you and yours connected to the cat.’

A willing hostage to him and his secret I asked, ‘But where is the key now? Is what’s left of the tablet of any use? And what about the people of Lahaj?’ So many of my questions remained unanswered, but now we were distracted by Latifah entering.

She carried fresh coffee and pushed Sa’idi away when he tried to fondle her. His wife screamed, ‘Get hold of yourself, I’m a married woman!’

‘Of course you are,’ said Sa’idi delightedly, ‘You’re married to me!’ She looked around in confusion and panic.

‘It’s me, Sa’idi! Don’t you see I’m the same, only younger?’

‘Stop fooling around. You’ll get me into trouble! Where is the man I married?’ wailed Latifah and then she began to cry. The old wife, hearing the commotion, came out and started shooing Sai’idi out of the place.

Baahir guided me out into the garden. ‘Better let him explain,’ and then under his breath, almost to himself, ‘it’s going to be tough.’ Hurrying down the Mareb road, Baahir Jalali promised to clarify it all for me. But as we headed toward Sana’a, he said we would save that story for some other time.

Do you think this piece is valuable? If so, you might consider providing us with financial support via Patreon, or simply pay us a small sum directly using PayPal: [email protected]. Thanks for supporting independent journalism. Subscribe for free to our monthly newsletter here.