In an undisclosed year, Decency took something marvelous away from me, and by extension away from you. Away from… I want to say, everybody. Decency took it, and left me…decency.

Decency now obliges me to make fiction of this, and set it far away and long ago, but how I want to blast that for the sake of its long debt to me, Seifert!* Hmm, Decency. Alright, then.

Long ago and far away, in an Eastern European country called…

(My own Soviet-bloc memento, from a time when we spoke in parables, is a little mental collection of those fictional Eastern European countries. Syldavia. Borduria. Rovenia. But I’m not going to use any of those; I’ve sworn off that, as you’ll see.)

In an Eastern European republic, called Padobron, at a pivotal juncture for me, when I was celebrating the derring-do of my expulsion from the Narodna Misočana Technical University (expulsion had become a countercultural badge of honor) the question of how to get a job was just beginning to grow on me, someone called Jaromir Seifel published something good. Something which everyone said was good, but which betrayed his true greatness by being first, published over-the-table by a state-owned press, and second, not as great as he was.

Small, in every way, our coterie was one of young people thrown together for being delivered by the same midwife, or confirmed in the same parish, or expelled for exhibiting the same cheek, or stuck in the same tavern-corner because they have the same feeble ideas of looking grown-up at twenty, but who believe that they’ve coalesced at the draw of stars and gods, through possessing a similar gallantry, genius, and destiny.

That May, my peers, whose dreams were to either reform or undermine collectivism, if not get a job within it, attributed to me a certain dashing, because of my expulsion, and because I wrote things, copied them by hand, and circulated them as if they were dangerous, like an authentic counterculture. I think the writing and the expulsion melded in their minds (though I was not, in fact, expelled for writing, but because of an uncle’s alleged black-market prosperity) and that they accorded me a position among them, rather like Seifel’s among the real writers and agitators. Seifel’s must have been the one because, though I had never mentioned him, when his Eight Roses appeared, Miroslav Kinsky and Petra Raha both told me separately that they thought I should read it, that I would like it. I learned later that neither of them had read it.

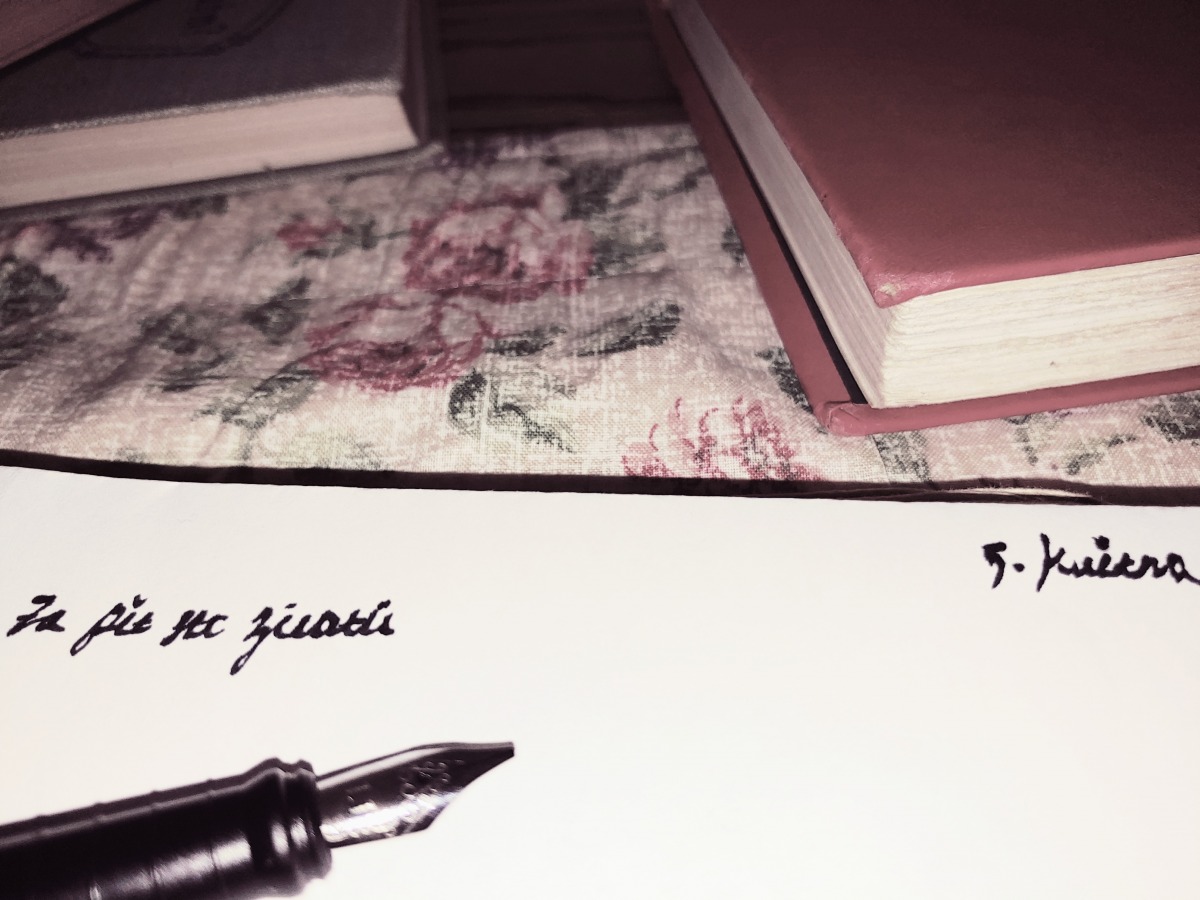

Well, what do you think I did? I bought The Eight Roses. I carried it quite proudly under my arm, with the spine showing nicely. I was only sorry it was so narrow; people might have to stop me, stoop, and stare to read it. Well, I was a little sorry, too, that the cover was such a hideous pink, like unhealthy skin. But I carried it, first to the “Golden Shield,” where I could casually let it be seen by two comrades in a corner, drinking a cheap wine our self-conscious slang referred to as ‘rope,’ and then home, for I was honest enough to read alone.

I read it. I was prepared, you know, to adore it, and I did. To the very last page, until, I saw what it might have been.

I don’t know how to talk about this. Love was never my strong point; I once described a man I was besotted with by saying, “In his striped sweater he looked like a large Easter egg,” and thought I was being poetic. When I want to talk about what happened in the blank space under the last words on the last page of Seifel’s The Eight Roses, my pen becomes enormous and my brain feels like the sort of thing you would serve in thin slices on a canapé tray. But allons! Seifel would be equal to this, so I will. On the page…

Oh, it was bigger than Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelungs, deeper than Meung’s Romance of the Rose, more universal than Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex; more romantic than Keats, tougher than Kafka, more acute than Tolstoy. I didn’t know all those names then, but I knew a thing that I knew was greater than all of them; since then I have known those names and something of what they are, but I have never known the thing of which I speak. I felt it then, and what I felt most certainly about it was that it was real. However clumsy, I would get it on the paper, it was real: what The Eight Roses would have been if Satan had never fallen. Don’t misunderstand me: I still adored The Eight Roses, and that’s why this thing was so big.

The thing was The Eight Roses, it was what would burst out of The Eight Roses if I could somehow slit the chrysalis. The huge joke was that Seifel had never known it was there. That was as plain as the sun; for if Seifel had known it was there, he would never have written the thin little state-approved thing with its hideous pink cover. Seifel was a genius, everybody knew that; he could have pulled it off. But he had dashed off this Eight Roses thing on table-napkins, probably, and sold it to the National Scholastic and Aesthetic Press, probably to pay his rent, and was probably flirting with his housekeeper while he scribbled the last chapter with his left hand. Even the title was botched. If he had written it two inches further into his peripheral vision, he would have noticed that good poetics, numerology, theology, plot dynamics, or even floristry would have made it either seven or nine roses. But no. He had eight.

I was stunned, goosepimpled, teary, prayerful with my gift. I wanted to kiss Seifel’s hands and put my wet face against his knees. I wanted him to lay his hand on my head and bless me, like Haydn blessing young Beethoven. He would see, he alone would see now, before it had pages and flesh, the great soul of my conception; he would laugh and be glad, though he had only been its modeler, that someone would bring the true Eight Roses into the world. I felt that Jaromir Seifel must have a rich, deep laugh, and a kindly, rounded face, lined from a thousand smiles. My writing hand curled. Before I knew what I was doing, I had piled ink, pens, my ragged notebooks on the tea table I used as a desk. The cleanest notebook was folded open before me, and I had written the date. Then…

Something was wrong, but not nearly so wrong as what was right; an inexorable force moved my hand to the left margin, my pen formed I,n, space, f,i,v,e…

The wrong thing, pain and roar, rose in my hand to snatch that first line from me. I wrote laboriously, shoving on my pen like Tepl’s Plowman of Bohemia.

“In five hundred lifetimes Mařek Klubaš would never see again what he saw now.”

The sensation was as if the bare lightbulb had fallen from its socket and exploded on the floor. I leaned forward, crouching over that single line like some terrible wound. For I posessed that greater Eight Roses, but the world could only have it at the price of my crime. This line was the identical line with which Seifel opened his Eight Roses. And this was not the only line of mine that would be identical with his. The first. The fifth. The eighth. The whole third paragraph… For Seifel was a genius, and even his garbage was partly immortal. This would be no wholly original cousin to Seifel’s book; the daughter could never be less than half her mother. That date I had dashed onto the top-right of the page got tattooed backwards across my hot, sticky cheek.

When I was upset, I had an unfortunate habit of pinching and rolling the skin on my upper arms, which left them blotched and bruised purple that night. As I lay on the floor with my feet on the bed, Barbora, my chaste, almost viceless, older sister, who was working at one of the electric plants then, came home and cooked something. She tried to get me downstairs to eat what she had prepared, and vaguely I remember that she entered my room very late, on one of her raids for my cigarettes, which she despised. Rooting through my handbag and both coats, she might have frisked me too, for all I did about it. I must have known when she fell asleep because later I remember suffering and even rationalizing out loud a bit.

So sure was I that Seifel would more than forgive me, I even wanted to give him the manuscript and beg him to publish it under his own name; I knew his upright soul wouldn’t do that, and although my huge, Beethoven-sort of ideas earlier would have considered joint publishing a condescension on my part, with the novel so much nearer now, in my fingertips, I was suddenly humble and realistic, and afraid that Seifel, the great Seifel, wouldn’t let his name stand by mine on anything. I was ready to write the thing and ask questions later, but both times I sat up at the tea table again, where that wrong thing, painful and roaring, stood between me and my Eight Roses. Seifel’s words would come next—only two words—and then mine, but I couldn’t write those two. I said them over and over. I said that second line to myself; it was beautiful when it first came to me, but I gave it a touch of assonance, switched a synonym, moved a verb, and it was even more beautiful. I chanted it to myself, under my breath, and the third sentence tripped after it like an obedient little sister; but I had to stop, because those three together broke my heart and I would have died

I sat Seifel in the broken swivel-chair opposite my bed, and said I wanted to approach this individually, head to head. We were alone with eons of space around us. What would it mean, if I took his clay pinch-pot ? Such a nice one! The best a pinch-pot could be—and made an Attic vase of it? Love! Miracle! Fate! Of course Seifel could see that. He was so understanding. He winked at me. Individual, elemental, primal, me and Seifel. There was nothing wrong at all. The sweat dried on my temples. We had been born for this, he in 1901 and I in ’38, so that he could write a little outline called The Eight Roses and I could make of it a lifegiving epic called, The Nine Roses. We would undermine Totalitarianism and fire noble, honest brains to seize the hour and steer democracy, social justice, and agrarian abundance. We would finally say what the haunted eyes of frescoed saints had wished the stuffy priests could. People would one day forget us, but humanity would ever be drawn into nobler lines. Again my face wanted to press Seifel’s knees.

I was at the tea table.

Pain. Roar. Wrong.

Seifel and I were not alone with humanity. Something that was never quite humanity gazed reproachfully on us, with their own just claims…the artists. For centuries, emaciated savantes had trudged penniless back to their shabby lodging houses because some plump profiteer was turning out penny broadsides of their intellectual property, pocketing everything with full blessing of the inept Law. What I found pain and wrong, was their long deferred hope of just protection. If even one copy of this epic, and even my inebriation knew it would cost something to print a tome of the size this would be, changed hands for a koruna, and Seifel, the most deserving artist of Padobron, would be robbed; his deep, thoughtful eyes—oh! I could see the tired, pathetic lines around them—would still smile on my work, would lose every pinprick of reproach in a selfless, true artist’s rejoicing at my victory, but I would be damnable. I may have knelt by his swivel-chair to ask his forgiveness; I don’t remember, but it wouldn’t surprise me.

Then, I could only go to him, Pán Jaromir Siefel of…wait, where did he live? Torný Street? And ask permission; like a hopelessly infatuated ragpicker going to ask for a Duchess’ hand. I could have bawled. The Duchess, of course, fully deserved my humiliation and my absurd, mad courtship, but I could not bear the inevitable rejection. Gallantry was hard and could bear it, but Love was soft and couldn’t. Too much was at stake for grandeur.

Maybe I did bawl; I don’t know.

Wouldn’t he give me full permission? In original and onionskin, signed and filed with the Department of Trades Protection? If I begged and orated, if I showed him five pages of prospective…? I was ashamed to fall back on this, but I was a girl, if a plain one, and very young; perhaps he would feel some gallantry—Wouldn’t he? Wouldn’t he?

Would he? What if he really had written it for his rent, and I came along, offering to outwrite and outsell him with his own book? What if he felt he couldn’t afford to split royalties on its improved revision? Or what if he only believed I would ruin it ? Thought me a…

Starstruck, egotistical, talentless, deluded…

Nineteen-year-old.

I was a nineteen-year-old. Oh, pain!

Unfortunately for that sickly pink book, my eyes fell on it at exactly that moment. How I hated it. Not what was in it. I hated Seifel, at the top of his career (I felt then that anyone who could publish articles in the Brava was at the top of his career), daring to dash off something so beneath his abilities and its own potential, to unload it on a literate, intelligent population, cased in airtight legal protections to keep earnest, less-endowed artists from ever achieving with it, what its semi-occasional flashes of genius taught them to love and long for. Oh, I hated his complacency. I hated his flirting with that fat housekeeper, I hated his hand paying the rent, I hated the half-koruna I had paid for the pink heartbreak.

I held it between my two hands. Never before or after was The Nine Roses so near me. Again it’s hard to talk about what The Nine Roses was, perhaps because the pain or longing was so acute that it is unconsciously suppressed. I know that one of the principal characters was a woman. I think she was to have been very important, and I know that she was only, in the vaguest way, suggested by ‘Marie Kepys’ in The Eight Roses, that she was profoundly, fundamentally different, not opposite, just so different that they must have been born in different spectrums of light. But for all that, I can’t remember anything about that woman. I know her name was Karoline Svít, that her hair was yellow, she was twenty-six years old, had ancestry in the mountains of northeast Padobron. That one side of her lower lip looked larger than the other, and that when she was nervous, she would blink a lot; but what she was—oh, it was stupendously human and yet inexplicable, unpredictable, something that blasted Determinism to bits, and yet, I don’t remember a thing.

Another character was deterministic, kind of a foil, who would be involved in a tragic devolution of some sort—obviously he was Heinrich Räder from Eight Roses, and I have to admit now, even with that neurotic curtain drawn across the shining glory of The Nine Roses, that he may have been its weakness, because I was too young to write tragedy well. But I am not sure of that. I’m surer, even now, of the greatness of that Nine Roses than of anything I’ve learned about writing since, which is a lot, at least compared to what I knew then.

It wasn’t Seifel across from me in the swivel chair then, it was humanity, posterity, and Art. Not the artists, but Art, with her own peremptory, maybe holy, demands, which were not the demands of the artists at all. Art sat in the swivel chair and smiled at me, her own old, youthful, smirking, blessing smile; my shoulder muscles finally released. I smiled too, with my head hanging to one side. The Nine Roses was not mine, had never been; it belonged to Art, loaned to me by her inscrutable purposes, and it was my part only to act, beatify the world, and disappear. The disappearing part especially soothed me. It seemed perfectly fitting and reasonable, just then, that if I produced the miracle and then disappeared, there would be no crime; I didn’t wonder how I would disappear…a galloping consumption, I suppose? An open manhole? This death-wish absolved me, to the extent that absolution is a psychological event, and I returned to the tea table.

I wrote only that second line, and not all of it, in its entirety. It was not a roaring, painful wrongness that stopped me; it was quiet, weakening my pen-hand. I turned around.

I was a bad Catholic then, a worse one later, and a poor one now; but God was in the swivel chair, and He was with the artists, the law, and the blasted State. I felt my own fists against my eyes.

You may have noticed that a good deal of that night is unclear to my memory, but the next part, unfortunately, is not. I was so tired and so…, I put the pen down, closed the notebook, stood, pushed my stool in, and pulled the light-cord. That was the end of The Nine Roses.

On pensive nights sometimes, I used to try to bring it back. Especially May nights like that one. More than once I walked into the Golden Shield with that hideous pink book under my arm, stood around, wandered back to our east-bank apartment, read the whole thing in one sitting, and stared at that last page, for minutes, more minutes, and then finally, a few more minutes. I don’t really know why I tried, knowing all along that it would never… Well, I used to wonder how the copyright would expire, cutting some unconscious inhibition that was keeping The Nine Roses from me. I even calculated its life-expectancy more than once; after the Berne Convention, it was based on Seifel’s plus fifty years… and he lived to be quite old. I’m even surprised I’ve outlived him. I don’t begrudge him for it.

In the seventies, I began to hope someone would find nine roses in eight, in some other century when Seifel’s work would be as free as air. But slowly I realized that the only person who would ever find it, was the one who found it that May night. What I saw was so tightly bound to what I was, to going in the Golden Shield, to my expulsion, to Miroslav and Petra, and the exact figure that Seifel was in Padobronsky culture just then, and the exact thoughts that went through my head reading his book, and the exact sickly pink shade of the cover of that particular edition. Perhaps someone reading some other genius’s potboiler will be gifted with an analogously grand reproduction. There are lots of those books about. As for The Eight Roses, I saw a used copy for sale in London a few years ago. Not in English; it was never translated, and it surprised me tremendously. Its copyright will undoubtedly outlive its sales. I think it’s out of print, unless a passage in that new Seifel anthology counts.

If this story comes to you just when a similar prospect is facing you, (and how can I forbid such a miraculous coincidence, when it has happened to me?) how shall I advise you? I could hardly urge, Write! I, who backed down, cringing and purehearted, from the stare of God that night.

But I know God now, Seifel better, the law and what the law is for. The only thing I don’t know better is an epic novel called The Nine Roses.

I regretted it for decades. I still do! But something different is precious to me now, as precious as the best Art was to me then. Perhaps not as precious! for I shall never feel so strongly again. Perhaps more precious than my estimates are : less storm and more truth. What I cherish now is the nineteen-year-old that pulled the light cord and went to bed, walking carefully around the broken swivel chair. Perhaps I understand God better, as I am more like Him.

For surely only He, who alone besides myself knew The Nine Roses, would say, “The girl is better than the book.” In that moment I chose to make art of myself. Was it worthwhile, for the sake of one night’s low-grade, possibly naïve morality, to give up what I still, only I!, know to have been so great? To throw away what so plainly told me it was bigger than the Nibelung, for a simple, few minutes’ act of elementary acceptance and approval? To forego a thousand master strokes in oil, for a single blunt stroke at human spirit?

Again and again I cannot answer it, as an artist. But an artist did not sit last in my swivel-chair.

Tonight, it is with a wonderous joy, I feel again something like that last page of Eight Roses. Not very like, for I do not feel in such storms now. But wonder, excitement, a glimpse of something better behind something good. That perhaps…

Oh, it is hard to write, my pen is enormous, and my brain is like…

Yes, that God, who sat in my swivel chair that night, holds a small, ugly, loved, but utterly unrealized work under His arm; that he will one day slit it and release the real…

I cannot say. He alone knows what it will be.

*Jaroslav Seifert was a writer, around whom revolved a competitive literary scene, made up of young people moving within the 1950s Czech counterculture.