In and between these lines I will explore aspects of the fascinating and dynamic relationship between music, identity and place. Reflecting on my own musical ventures, as well as turning to secondary sources discussing theoretical concepts on the topic, I will point to various ways in which one’s relation to a place is both reflected in, and actively imagined and reinforced with the help of music.

I will also discuss the idea of music as a place in itself. Representing a world that seems to lie somewhat apart from our everyday life, the entrance into this ‘parallel world’ can give a strong sense of connection to our surroundings, to the world, and not least to our selves. For the travelling musician, it can serve as a place they can carry around with them and thus feel at home wherever they go.

A child’s venture into a parallel world

This piece is inspired by my own experience of living and musicking abroad: turning my Austrian ear and heart to traditional musics from Ireland, which has been my home for the past 12 years, and gradually planted seeds for the creation of tunes and songs that would combine elements of Austrian and Irish music traditions. At the same time, North Indian ragas, odd meters and Swedish polska rhythms – which I came across on my travels – started to extend the palette of colours with which I paint on my musical canvas.

Upon reflection it became clear to me that the practice of combining different musical elements, standing in connection to particular places and peoples, allow me to reconcile multiple new identities and connections to new places without losing a strong connection to the place and culture within which I grew up.

Furthermore, forming neither entirely part of the here nor the there – neither Austria nor Ireland or elsewhere, this music seems to present a place in itself that instills me with a sense of connectedness. It provides a place I can retreat to wherever I am in the world. In this music, I feel at home.

II

In September 2005, seeking to learn Irish tunes in their ‘natural environment’, I accidentally emigrated to Ireland. It had been my intention to spend a year abroad after finishing secondary school. But when the time came to return to Austria I simply stayed put, having fallen in love with the West of Ireland: its beautiful shades of green; the wild Atlantic; the mountains; rivers; the people and their music.

Prior to moving to Ireland, I had been forced to rest my hands for an extended period due to a bout of tendonitis. In my newly found home of Sligo I took up playing the violin again, under the guidance of my friend Rodney Lancashire.

A ‘session’ in Foley’s Bar, Sligo.

Beginning anew, I left behind everything else I had learnt, fully immersing myself in Irish traditional fiddle playing. Only later, over the course of academic studies at UCC, did I slowly reconnect with my earlier musical identities. These lay largely in European Classical music, which I had studied on various instruments since the age of five, and Austrian traditional music, which I got involved with through local folk festivals during my teenage years.

Next to Irish traditional music, I started to practice diverse musical traditions, including North Indian Classical music, which I studied intensively during a three-month stay in India, shortly before I enrolled in UCC.

Moreover, I made first attempts to compose my own music. One of the first pieces I wrote was ‘Austrindia’: its melody is based on, but doesn’t entirely stay faithful to, the scale used for Raag Charukeshi, an early evening raag I had studied under Pt. Sukhdev Prasad Mishra, in Varanasi, India.

Yodeling on top of BenWiskin, Sligo.

I experimented with singing the melody in a yodelling style, a vocal technique derived from Austrian traditional singing practices in which notes are approached in a direct way from the chest to the head voice, causing a distinctive breaking noise characteristic of this type of singing.

This first attempt to bring my different musical worlds together brought a strong sense of fulfilment, inspiring further compositions in a similar vein, including ‘Like Lisa’ and ‘Jodlfunk- Da Alma Zua’. These also feature yodelling techniques like ‘Austrindia’; this time, however, the yodel is set to modal scales, more typical of Irish traditional music.

Both ‘Like Lisa’ and ‘Jodlfunk- Da Alma Zua’ include sections carrying elements of Irish traditional music: the middle part of ‘Like Lisa’ is a tune in g mixolydian. Although adhering to the scheme of two underlying rhythmic cycles of seven bars of 7/8 and one of 5/8, and three bars of 7/4 and one of 6/4, the phrasing of the bow and ornamentation such as cuts and rolls is strongly reminiscent of an Irish reel or jig.

III

Upon reflection I realise that, in their various different ways, all of these compositions strive to unite my home place of Austria with my newly found home in Ireland, as well as other places such as Varanasi in India, which are close to my heart.

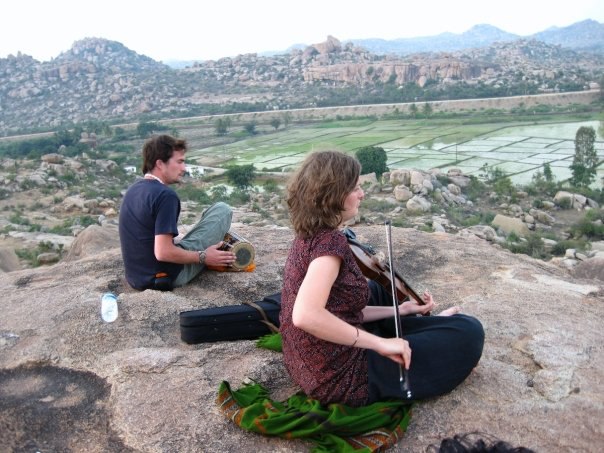

Playing in Hampi, India.

This, as I became more and more aware during the course of my research for a dissertation project, provides me with a sense of continuity in what I do and who I am, helping to express myself authentically as a musician and individual. It provides me with a certain stillness. I can be true to myself, and avoid feeling that I have to ‘hide’ or ignore any one part of me.

I further realised that what I conceptualise as ‘place’ is much more than a specific landscape, cityscape or physical environment. It also includes certain sounds, memories and, more than anything, the people I associate with that place.

Moreover, it became apparent that diverse places don’t merely co-exist in my music: at the moment of performance, they form an entirely new place, without any fixed geographical position. This place has no literal geographical basis, though it does foster a ‘placeness’ of a different order, in the realm of the sound, to which I can retreat whenever I play.

When I perform my own music, or music with which I am at home at the same level, I feel a strong sense of being transported to this ‘parallel world’. This develops a bond with a higher form of truth, that lets me go a step beyond everyday reality.

As a musician adhering to a modern vagabond lifestyle, music offers the possibility of entering this place no matter where I am. It is a constant in ever-changing surroundings that enables me to bring my home with me, wherever I go.

IV

Place may be conceptualised as far more than a mere geographical location: like everything else we experience, our concept of place is tied to the mechanisms of perception. Thus, incoming stimuli from the outside world are taken in and consequently matched up with our cognitive frameworks.

These in turn are crafted with the help of our knowledge, previous experiences and memories. It follows that our concept and perception of place is a construct of mind that only partly relies on certain physical surroundings, a land- or city- scape.

Alpine Austrian music session outside hut.

Similarly, when discussing America’s ‘invisible landscape’, folklorist Kent C. Ryden describes places as ‘fusions of experience, landscape and location.’ Quoting geographer Yi-Fu Tuan he explains how ‘the feel of a place is registered in one’s muscles and bones’. For Ryden, the kind of feeling that we get for a place when we get to know it better constitutes ‘a unique blend of sight, sounds, and smells, a unique harmony of natural and artificial rhythms such as times of sunrise and sunset, or of work and play.’

Issues of place and identity are more and more relevant in an increasingly globalised world. Moving from country to country is becoming a regular and normalised activity for many, if not most of us. As a consequence of our vagabond lifestyles, many different places form parts of our identities. It can feel like we are at home in a number of places, or in no place at all.

Rapport and Overing explain that anxious advocators of an ‘idyllic past of unified tradition’ express their concerns that ‘individuals are in transit between a plurality of life-worlds but come to be at home in none’.

At the same time as feeling a connection to more than one place or experiencing a sense of homelessness, it can appear that we are literally in more than one place at the same time, or indeed in no place at all. This is often due to modern technology, which may lead to a perception of a virtual reality lying beyond any objective or physical reality.

In his discussion of the consequences of modern life, Giddens explains how through the advent of modernity, space became disconnected from place. Through the invention of maps that would represent the world from a universal and objective viewpoint, we came to conceive of something Giddens refers to as ‘empty space’ as an entity in itself that is no longer connected to a specific physical setting. The existence of space as something that has no boundaries or specific meaning recalls Stilgoe’s definition of ‘landscape’ that stands in opposition to natural ‘wilderness’:

a forest or swamp or prairie no more constitutes a landscape than does a chain of mountains. Such land forms are only wilderness, the chaos from which landscapes are created by men intent on ordering and shaping space for their own ends (Stilgoe, 1982).

Music is an effective means of inscribing meaning onto space and express a relationship to it. According to Jaques Attali, our very distinction between music and noise reflects the distinction between ‘culture and nature’. Through engagement with music we erect boundaries that define if something is a ‘place’ or ‘space’; if something is ‘home’ or ‘foreign’; or if something belongs, or does not. Consequently, social, individual and geographical borders are reflected in music, which inform a sense of place.

Music can be used to differentiate between different places and people, but it can also serve to expand boundaries linking ‘homeland’ to what Mark Slobin refers to as ‘hereland’. It creates bonds between different countries, and links to any place one wishes to be at or belong to.

Moreover, it has the potential to give us a sense that we are all connected to all places, at all times. This appears to be the spirit behind so-called ‘Ethno festivals’ happening all over Europe, which bring together young people that exchange their folk musics.

Ethno-in-Transit.

Individual musicians, groups and entire nations link and separate themselves, their places and people with the help of music in various different ways. We sing, play, compose, listen and dance to music that carries references to specific locations, or indeed travelling or being ‘on the road’, in the form of song lyrics. We engage with, and create music that contains imitations of sounds that occur in particular places, or as Zuckermann points out, the frequencies of a physical environment.

Slobin states that we ‘domesticate’ what to our ears is foreign music and adapt it to make it our own according to commonly shared agreements of what our own music is. We engage in what Slobin refers to as ‘code-switching’ in order to shift between a number of different musical styles or to layer different styles of music on top of each other in one and the same piece. We share and associate ourselves with music that to us reflects the feel, the shape, and the people of a place.

V

Given that any space can be turned into a place through the assignment of meaning to it, it can feel like the involvement with music – be it through listening, playing or dancing to it – creates a place of its own.

Victor Turner explains how as part of our ever-repeating social dramas we enter a ‘liminal’ space, a kind of parallel world that he describes as ‘neither here nor there […] betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial’. According to Turner, it is this period in which we are somewhat apart from our everyday life that both mirrors the nature of our artistic involvement and is advanced by it. This place has its own rules, its own reality and its own time: that of the present moment.

Alfred Schutz explains how music, due to its polythetical structure, is conceived of step by step rather than as a whole: a time zone apart from quotidian time. He explains how music unfolds in what he refers to as ‘inner time’. Thus, when we perform, we share our own ‘stream of consciousness’ with that of the composer: ‘two series of events in inner time, one belonging to the stream of consciousness of the composer, the other to the stream of consciousness of the beholder, are lived through in simultaneity, which simultaneity is created by the ongoing flux of the musical process.’

Claudia Schwab and Matija Solce.

When we play music together, we equally tap into each others’ streams of consciousness and together ‘live through a vivid present’. In addition to sharing ‘inner time’, the music is lived through in ‘spatialised outer time’. Thus Schutz says both ‘share not only the inner durèe in which the content of the music played actualizes itself; each, simultaneously, shares in vivid presence the Other’s stream of consciousness in immediacy’.

When Schutz explains the musical process of ‘inner time’ he adds that ‘when for one reason or another the flux of inner time […] has been interrupted […]’, the performers might have to fall back on devices measuring ‘outer time’ in order to play together.’

Pleasurable as it is, not every musical performance brings with it the experience of dwelling in a parallel world: a more intense and lasting experience of entering a different place seems to be related to the ability of staying in the present moment.

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi conceptualises flow as ‘the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter’. He explains how ‘in the flow state, action follows upon action according to an internal logic that seems to need no conscious intervention by the actor […] there is little distinction between self and environment, between stimulus and response, or between past, present and future’.

*******

Claudia Schwab (photo by Peter Crann).

Place, with all that belongs to it, including memories of home, connections to certain peoples and their music or the impression of distinct landscapes, undoubtedly plays a fundamental role in our understanding of self. A strong connection to a place creates a sense of belonging, and thus of home. Furthermore, the experience of entering a form of parallel world that lets us be aware of a higher plain of existence speaks for the fact that music can be seen as place. In this place, we can find a deep connection to ourselves. We can feel the togetherness with others, satisfying our innate need to be understood and to be with other people. It is a place that we can carry with us, that can make us feel at home wherever we are in the world, and glimpse an alternate form of reality. This has certainly been my experience of gallivanting around the world as a musician.

This article is based on Claudia’s thesis, completed in September 2013 while studying for a Masters in Ethnomusicology in University College Cork.