Back to love and sex. Liking is preferable to loving – and less conducive to heartache. Youth is oblivious to that boring truth.

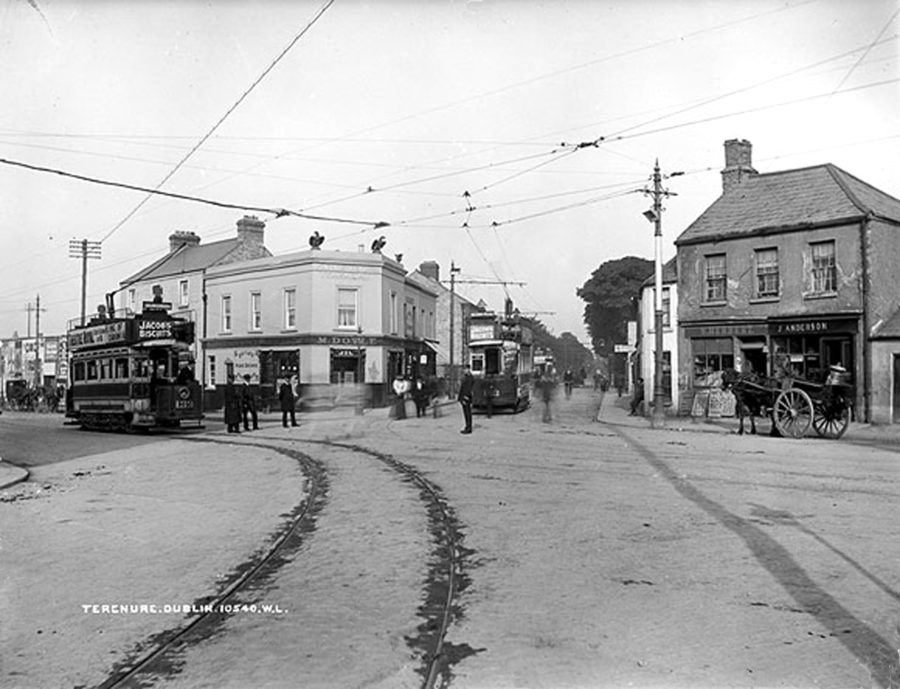

The unbiddable first love of my life lived in Terenure, Dublin, a half a mile away from me and I called her Thaura Mornton. We were equally devoted to amateur theatricals.

She was sixteen when I, returned from my first migration to London, standing in the wings of the Marian Hall, Milltown, first saw her onstage singing ‘Tony from America’, a number from Lionel Monckton’s ‘Quaker Girl’ musical comedy. In the middle of the song she grinned offstage and winked at me. I was smitten. She was an elusive butterfly and led me in a delightful gavotte during the years when I was a recidivist emigrant. Thaura was spirited, an only and over-protected child. Her loving father once warned me that whatsoever male harmed her would find a loaded shotgun lodged in his posterior. And discharged.

At night, therefore, she would climb through her bathroom window, negotiate the roof of a rickety shed and make her way to the hop in Templeogue Lawn Tennis club, amongst whose hormonal boys and girls was the much-adored rugby international, Tony (later Sir Anthony) O’Reilly.

Inevitably Thaura became pregnant, sadly not by Tony or me, had her baby adopted – in the nineteen fifties girls had little choice – and was taken on a grand tour of Europe by her maiden aunt. I still possess the single breathless postcard she sent me from Rome; ‘Everything is so beautiful’, she wrote.

When she returned she still led me in a merry dance of frustration and obsession. When I saw the film Carmen Jones – Hammerstein’s improvement on Bizet’s opera – I understood her better. She even looked like Dorothy Dandridge. For me she was that love which is ‘a baby that grows up wild and won’t do what you want it to’. But the chase was everything. I saw her as untamed, the perfect companion for my adventures.

When the Betty Ann Norton School of Acting decided to put on an amateur production of Thornton Wilder’s ‘Our Town’ they cast Thaura and myself in the lead parts of George & Emily. My joy was unconfined: my romantic delusion and myself would be working closely together every night for a few weeks. The idyll lasted a single rehearsal when the director became ill and the show was cancelled. Life went frustratingly on, punctuated by hard-earned rendevouz which the lady in question often cancelled at short notice. I simply could not understand her.

However, walking her home one evening after a film in the Theatre De Luxe cinema in Camden St., she demanded: ‘When are you going to get a real job and settle down?’ At twenty-one I had already been a bored civil servant, factory worker, failed student and aspirant writer, unemployed again.

The penny dropped; she wanted security, had become broody. Her question made me realise that even her irrepressible spirit had bowed to the ambitions of muddle-class slurbia. It was like the Invasion of the Body Snatchers. She had contracted ordinariness, had capitulated to respectability, to browbeating nuns and Christian Brothers, to frowning teachers and concerned parents to whose concerns I had never managed to pay attention – which fault she had easily identified in me. I was not what she actually wanted in a mate. So, as per usual I ran and as usual was wrong.

In the following years Thaura and I had the occasional brief reunion. Years passed before she kissed me goodnight with the softest lips in the world. I was on the point of emigrating again, this time to Canada and here was my lost love suggesting I take her with me. I thought long and hard, regretfully said no. Her reverse capitulation had come too late. By that time I had also shifted my sights, adopted a different ambition, that of changing the world. It was by now the nineteen-sixties and I was still baying at the moon.

Even more years later, each well married to strangers, Thaura and I together polished off a bottle of whiskey in one sitting. We laughed and mocked our younger selves until tears came to our eyes. I lost touch again, forever. I heard that she died sitting alone in her armchair, aged fifty something. We had never become, in the biblical sense, one.

Bob Quinn, pictured in 1952.

There always is, or should be, somebody like that in a life. James Joyce got it right in ‘The Dead’: a might-have-been love against which no subsequent union can compete.

The need for the ‘one’, a real or imaginary at-onement, is a powerful urge springing from our time as protoplasmic life forms which reproduced themselves. They can’t have had much fun four million years ago… they merely split in two. Once those simple organisms were divided we were lost, like garden worms bisected by a spade, wriggling frantically to find our other half, condemned to seek a soulmate who would spiritually complete them – and satisfy basic drives.

‘All man’s miseries’ wrote Blaise Pascal, ‘derive from not being able to sit in a quiet room alone.’

Gradually, the most elemental human instinct was romanticised and called love. Worse, for us naïve Catholic youngsters the delightful illusions of romance were transubstantiated into a spiritual straitjacket. In Christian circles it was called ‘atonement’ and cleverly channelled into a guilt trip about sins to be atoned for. What a joke! We would have been better left to our own devices, even if it meant being Tom Eliot’s ‘ragged claws, scuttling across the floors of silent seas’. The psychic wounds acquired in that battle between religion and libido left scars forever unhealed and unsuccessfully ignored. Ask any celibate priest.

Religion was the first and most successful multinational industry in Ireland. The only native entrepreneur who could compete with it was Arthur Guinness. My father and one brother each spent forty years in St. James Gate Brewery constructing barrels for Uncle Arthur’s brew. This aversion therapy meant that neither died of the free beer or ruined livers, the fate of many of their fellow tradesmen.

Before Guinness arrived the Irish Bishop seems to have made an unspoken pact with the Irish Politician: ‘You keep ‘em poor and we’ll keep ‘em ignorant’. Soon he made another treaty, this time with Arthur Guinness: ‘We’ll keep ‘em ignorant and you keep ‘em drunk’.

The Bishop would never tolerate earthly aspirations. His and the brewer’s captive imbibers of Faith ended up as guilt-ridden, frustrated, self-flagellating, unhappy topers. Many intelligent Irish males suffered this fate and justified silent movie star Louise Brooks’ description of us as ‘the worst lovers in the world’. Some did their best to avoid emasculation. They became entertainers, poets, novelists, journalists, fast talkers, hustlers, petty criminals, moneylenders, politicians, bankers and other drunks. But they kept on wearing the green jersey and going to mass on Sunday.

My father was a lifelong teetotaller because his own father – also a cooper, as were all his forefathers back to 1798 – had died young and alcoholic. In my long life I may have consumed beer enough for all three of us.

Drunkenness was a sin; but did you know that the respectable business of banking was also once a sin, worse, a ‘mortaller’, as we knew it. In more frank times banking was called usury or money-lending and was damned by the major religions. Now the innocuous term ‘banking’ covers a multitude of heinous crimes in comparison with which drinking is akin to being in a state of grace. Banking is no less than usury in a collar and tie. At least pawnbrokers were a service for the poor. On Fridays, on my way home from Synge Street school in the No. 83 bus queue at Leonard’s Corner I would notice weary Kimmage housewives bearing their husband’s good suits home, having redeemed them from the pawn shops in Camden street where the precious garments had lain since Monday morning as security for borrowed money.

Up to medieval times the only people forced to dirty their hands with lucre and commit the sin of lending at exorbitant rates were Jews because they weren’t allowed do anything else. When that talented people demonstrated what an excellent way it was to make money, the Christians (notably the de Medicis in Florence and the merchants of Venice) took over the business – ‘How odd of God to choose the Jews’ – damned the unfortunates as God-killers and respectabilised their own unscrupulous moneylenders by calling them bankers. As Gore Vidal pointed out, human beings are enemies of all vice that is not directly profitable.

Historical, anti- Anti-semitism’s roots may be a perverse symptom of Christian guilt. i.e. embracing the sin, hating the sinner.

Read the first installment of Bob Quinn’s memoir here.

We rely on contributions to keep Cassandra Voices going.