Seemingly out-manoeuvred by more experienced, and ruthless, political ‘partners’, the Five Star Movement (M5S) has entered a crucial phase after forming a coalition government with the right wing La Lega. The key question is whether the issue of immigration will continue to dominate Italian political debate, or whether M5S can bring about meaningful social reforms. For the moment it is advantage La Lega.

I – La Lega Leading the New Government

After three months the new Italian government composed of M5S and La Lega is facing difficulties in aligning a complex mix of political leaders, many of whom are in power for the first time. The clash of conflicting ideas and constituencies, played out in newspaper articles and websites, brings to mind – not only to foreign observers – a stereotype of Italian political chaos.

The ‘yellow’ (as MS5 are referred), having earned 32.4% of the national vote in the March election, on the basis of an economic platform leaning towards socialism, should be leading the coalition. But this mantle seems to have been usurped by the minority ‘green’ (La Lega) partner, which gained 17.6% of the vote. The has been achieved through Le Pen-ist propaganda, focusing on migration, security issues and Euro-scepticism, while winking to Trumpism (and esteem for Vladimir Putin).

Matteo Salvini, the leader of La Lega has emerged as the public face (and sole heir of Lega father Umberto Bossi, following his forced retirement after charges of public finance misuse) of the government. He is Deputy Premier and Minister of the Interior; while his supposed ally, and interlocutor, Luigi Di Maio, the leader of M5S, is Minister for Labour and Economic Development. The factions are supposedly being coordinated by Premier Giuseppe Conte, the M5S nominee.

Salvini has injected atavistic fears of a foreign ‘other’ into political debate, highlighting criminality and legality, loss of jobs and waste of resources, as well as undeserved social spending in a period of economic crisis. Within days of entering office he stated to the media that he wished to divert five billion euros from migrant reception and integration policies, while ramping up anti-EU rhetoric.

In June 2018 he closed Italian ports – in particular the ports of Sicily – to the ‘Acquarius’, a ship from the fleet of the NGO ‘SOS Mediterranèe’ (MSF – ‘Doctors Without Borders’), sailing from Libya with six-hundred-and-twenty-nine migrants (including one-hundred-and-twenty-three unaccompanied minors) aboard, which had previously been prevented from entering La Valletta in Malta.

Salvini invited the captain, ‘to continue the crusade with all its comfortable services along the Mediterranean costs’, as far as Valencia, Spain, where the new Spanish Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez authorized it to dock. He then told another ship the ‘Lifeline’ it had no chance of entering Italian ports, and went on to ask his EU partners to consider radical changes in EU migration policies.

On August 2018, he created an internal conflict within the Italian Guardia costiera (‘Coastal Guard’), prohibiting another ship, the ‘Dicotti’, from unloading one-hundred-and-fifty migrants in Catania, Sicily, and then instigated what seems to have been a politically motivated investigation into the Agrigento public prosecutor Luigi Patronaggio on several charges, including abduction and segregation, illegal detention and abuse of public administration.

At the end of August 2018 he met the anti-EU and Far Right leader of Hungary Viktor Orban, theorizing on the so-called Democratura, or ‘Authoritarian Democracy’, while endorsing the Hungarian leader’s policy of closing his country’s borders to migrants.

Astonishingly, according to a majority of Italian commentators, in view of recent polls, Salvini had mastered the situation and, by escalating declarations, had emerged as a real political animal, front and centre of the political stage, to the detriment of the M5S.

In reality Salvini has been in election mode since the formation of the government, as he awaits another opportunity to go to the polls, with surveys showing his party appealing up to 30% of the electorate. This could allow his party to reconcile with former allies, and enter a coalition with the former fascisti Fratelli d’Italia or Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia.

II – Transatlantic Connections

But the rapture of opinion writers can be misleading. Another Matteo (Renzi)’s recent adventures have shown the volatility of Italian voting intentions in an era of social media. Nothing should be taken for grant at this early stage in the electoral cycle.

Certainly Salvini’s political position has been strengthened by an axis with other Populist forces in Europe and throughout the world. Apart from reciprocal cuddles with Marine Le Pen, and the muscular chest-to-chest recognition by Putin, there are also bonds with the US Presidency. This has served to legitimate him and his party.

Salvini and other Italian right-wing parties see the 2016 US Presidential election as a sign of a shift in Euro-Atlantic politics away from buonismo, and ‘human rights-oriented policies’ deemed to be weak, inefficient and unpopular

Indeed, Attaccateve al Trump, a book by Paola Tommasi, with a degree of notoriety in Italy, credits the dissolution of the Italian Christian Democrats with the unlikely election, ‘Berlusconi-style’, of the outsider Trump.

Steve Bannon – Trump’s former consultant and spin-doctor – has hailed La Lega as a part of the constellation of ‘Breitbart’ (and perhaps Cambridge Analytica?) declaring with some confidence that ‘the Italian fellows are doing a good job’. Subsequently, Trump, while fomenting against Trudeau (as he travelled back to Washington from last June’s G-7 in Canada), recognized Italy as a primary political partner and warmly welcomed the new Italian policy on migrants.

Tellingly, both governments during their first days, created a storm over migration issues. Trump followed up victory by imposing visa restrictions on migrants arriving from selected countries, which generated street protests in the principal US cities. He has recently had to cope with a reversal in public approval on account of the shameful separation of children from their parents at the US-Mexico border, and incarceration in small cages, but his wife Melania’s apparent repentance was perhaps designed to balance the effect.

Salvini’s declarations on migrants issues also unleashed an emotional wave, expressed in national press and television, where commentators weighed in to contest human rights violations and defend the previous government’s policies.

But, as indicated, the overall effect on voting intentions appears to have been favourable for Salvini. Recent polls suggest his anti-intellectualism, and jibes about buonism, have galvanized a significant part of population. Many appear to appreciate his ‘muscular’ approach both in internal affairs, and in dealings with EU partners.

III – Democratic Impasse

The Democratic Party, out of Palazzo Chigi since the March elections, ending the premiership of Paolo Gentiloni, but with Matteo Renzi still on board, have proved ineffectual in opposition. A new leadership has still not emerged, and the old one never developed a comprehensive political platform for these challenging times, apart from to say: ‘we lost, it is up to them to govern’; meaning, in essence, ‘we remain on the side of the river hoping that corpses of political adversaries will pass by’.

The new (transitional) political secretary Maurizio Martina – appointed after the electoral collapse to keep a steady course before the next congress – has, unsurprisingly, inveighed against Salvini. In parliament there have been many pious statements from ambitious Democrat deputies attacking the approach of the Lega leader, but meaningful initiatives have been lacking thus far.

After falling from a high of 40% in the European elections of 2014 to just 19% in the March election a perception has emerged of a distinct lack of consensus in the Democratic Party. Energy has been wasted on strategies designed to compete with other party’s web presences, without producing any visible impact or, even worse, running an ‘opposition within an opposition’, against the left wing (‘former communists’), who are castigated for not toeing the leadership’s line.

The fallen ‘Matteo’ underestimated the ill-effects of simplistic proposals on institutional reforms, investing too much rhetoric on the efficiency and rapidity of political outcomes. He remained devoted to a Blairite ‘third way’, without any deep reflection on the future of centre-left politics in an era of shifting economic and technological plates. There were no original policies on equality or redistribution of wealth, no weltanschaung for Democrats in the years to come.

Affected by a curious ‘Zelig-style’ syndrome, leading to the party co-opting other parties’ proposals (on immigration, public funding of politics and cutting costs of institutions), the Democrats under ‘Matteo the 1st’ shared with ‘Matteo the 2nd’ a certain ‘muscularity’ in the tone adopted towards European partners, political adversaries (within and outside the Party), bureaucracies and allegedly ‘strong powers’. But they never renounced an associations with large corporations or the institutions of European financial orthodoxy, as they sought to retain the support of a shrinking constituency of moderates.

As a result, left-wing supporters left the party in droves, especially to the M5S. Beffa delle beffe, though not unexpectedly, at the last elections even former moderates seemed to prefer the more consistent right-wing voice of La Lega.

The Democratic ‘Matteo’ has divided his own party – and wider Italian society – pitching two sides against one another. One derives from the Catholic Democrazia Cristiana (later Popolari and Margherita), while the other stems from the former Partito Comunista Italiano (later Partito Democratico della Sinistra and finally Democratici di Sinistra).

Aldo Moro – compromesso historico.

After the election, ignoring the lesson of one of its greatest leader Aldo Moro – the great exponent of compromesso storico between Christian Democrats and Communists – he refused to countenance any convergence on social issues with the M5S.

In this depressing scenario, a strong answer to Salvini came from Roberto Speranza, the young leader of Liberi e Uguali (‘Free and Equal’), the political party that emerged from those groups leaving the Democrats before the elections, under the leadership of Massimo D’Alema, former Premier and Communist leader, in opposition to Matteo Renzi. Speranza reported Salvini to the prosecutors’ office in Rome for instigating racial hatred.

Indeed numerous public declarations and decisions taken by the green-yellow alliance appear inconsistent with constitutional values, and international laws to which Italy is bound by treaty.

In the ‘Acquarius’ case, as in the more recent ‘Dicotti’ case, Sicily was the safest port to dock, rather than Valencia. Any practice by Italian military forces involving returning migrants to Libya before security and peaceful conditions have been restored runs contrary to the European Court of Human Rights-stated principle of ‘non refoulement’.

IV – What does the M5S Stand For?

As regards the M5S, which is based on the principle of digital democracy and contesting Italian ‘cast’ politics and patronage, it is not clear what it stands for.

Doubts have been raised about its initial roots in a project of ‘community behavioural analysis’ by one of its founders, the ‘Internet guru’ Roberto Casaleggio, who died in 2016, but whose legacy has been carried on by his son Davide, with even greater efficiency.

M5S is associated with a private consultancy firm that seemingly derives financial gains from political information and advertising. The firm can also organize political communication and harness the vote of M5S, contrary to democratic principles enshrined in the Italian Constitution, which predicates democratic participation on political organizations, and freedom of individual political consciousness.

A stronger juridical stance against these new forms of political organization risks having any decision being twisted to reinforce populism. Moreover, any rejection by the court of such charges would be a sign of the failure of traditional constitutional instruments.

A finding against M5S would solidify a public perception that public institutions are anti-democratic – just as when the government was being formed President Mattarella was accused by the ‘piazza’ of inappropriate interference over blocking the appointment of Paolo Savona as Minister of the Economy.

What then for the new Matteo? Time runs fast but it is too early to appreciate the impact of Salvini’s strategies, in particular if he will last better than the ‘other Matteo’ on the prow of the Italian Government ship, and in the hearts of (certain) Italians. While a significant constituency has been galvanised by what appears to be a certain strength of personality, still the percentage of Italians who have ever gone as far as voting for La Lega amounts to a mere 5.6 million, out of over 51 millions of voters.

Far more of Italy’s citizens are seeking new voices supporting civic ideals, under a new Democratic leadership.

A turning point might be the opposition within the M5S to common political action with La Lega. This has already been seen at local level since the beginning of unnatural alliance: in June 2018, in response to Salvin’s repeated denunciation of migrants, Mr. Nicola Sguera, a city council member in Benevento, resigned declaring ‘We hoped for ‘Podemos’, now we have ‘Orban’’; for similar reasons Carlotta Trevisan resigned her role as deputy president of the city council in Rivoli.

At a national level their leader Di Maio has hushed up criticisms declaring: ‘I want suggestions, not complaint: now we run the government’, and recently declared in Versilia, that ‘misunderstanding and conflicts are not surprising, we will do our best’, and that ‘blockages and ‘refoulments’ cannot be made with kindness’.

However, the recent Roman meetings of M5S, before and after the summer parliamentary recess, witnessed further grumbling by the left-wing of the movement, led by Senate President Roberto Fico, who declared, contradicting Salvini and his leader Di Maio, that ‘Italian Ports shall remain open to NGOs, they are doing an essential job”.

Moreover, Barbara Lezzi, Minister for the South, Senators Elena Fattori, Paola Nugnes and Luigi Gallo are among the deputies showing commitment to the idea that ‘refoulments’ are not a policy appropriate for a civilised country. Fico also came out against the meeting on August 28th between Salvini and Orban, declaring, ‘there’s no political leader more distant from me in Europe’.

Worse still, after the meeting between the two Far Right leaders and the final declarations on a common stance in Europe (with the schizophrenic Salvini supporting the Orban position against migrant re-locations in the European Union, contrary the official position of his government), Prime Minister Conte leaked to the media that it was no longer possible to have an official public position.

V – The Reality About Immigration

The political context could easily evolve differently between the right-wing La Lega politics and the leftist M5S, which is animated in particular by opposition to the elitist politics of the Democrats, and is still rooted in the family photo album of la sinistra italiana.

There is a compelling argument that the whole ‘immigration affair’ is a lot of hot air, and part of a complex public relations campaign being orchestrated by unscrupulous politicians ‘senza arte né parte’ (‘without any virtue nor strong political faith’), for whom the M5S is naively providing a stage and microphone.

Its impact is increased by the inability of Italy and the EU more generally – blackmailed in part by their own constituencies – to agree on a real and effective common migration policy.

According to official United Nations reports, collected in the World Population Prospects – and reported in the ‘Huffington Post’ in 2017 – migratory flows into Europe from 2000 to 2010 were 1.2 million people per year, which makes up a mere 0.2% out of a population of five hundred million inhabitants (one million have arrived in the United States over the same period).

That figure then dramatically fell to 400,000 entries per year between 2010 and 2015 due to the Economic Crisis, which led to less money being remitted to sustain travel costs from Central, Western or Eastern Africa to Europe.

According to ‘Liberazione’, these numbers will have declined further in 2018: 8% less have disembarked on the Italian coast than in the same period last year. Data from the Ministry of the Interior indicates that 14,441 people arrived in Italy by sea in the first six months of 2018, while 64,033 had arrived in the same period of the previous year. This is not to say international migration is not a genuine issue, but it puts it in perspective.

In 2015 the United Nations said international migration had reached 244 millions per annum, 20 millions of whom were refugees. That number had grown from 154 millions in 1990 to 175 millions in 2000. Migrations will persist as long as economic cleavages exists between rich and poor countries. The real point is the small proportion of those, about one million, actually entering Europe, the biggest economy in the world (comprising 23.8% of the world’s GDP, against the 22.2% of the US), with 500 million inhabitants, compared to total migrations around the world.

The essential issue is how to adopt efficient, humane and stable institutions for the governance of humanitarian emergencies and economic migration to Europe.

Instruments to deal with economic migrations are not easy to be put in place. Decisions touch on political ties with foreign states, anachronistic colonial attitudes, distribution of military and security power, sovereignty over international waters, irrational beliefs and ancient fears, as well as normative politics.

Meaningful measures are, however, on the table for European governments to discuss. For instance, Angela Merkel recently proposed a common EU force for border control. Indeed, even in the absence of intense passions, a European Agenda on Migrations has been debated since 2013 among EU leaders, and the Migration Compact proposed by the previous Italian Government envisaged a scheme for infrastructural investment in Africa.

In this context, the EU’s ‘La Valletta Fund’ continues to provide financial support to projects tackling the ‘root causes’ of migrations in selected African countries. The new strategy of the European External Action Service – the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the EU – includes closer ties and relationships with Europe’s ‘neighbours’, and the ‘neighbours of the neighbours’ from where migrants leave for Europe (not only North Africa, but also Sahara and Sahel countries).

The EU social agenda, debated since 2015, also contemplates rules and measures for social integration of migrants, within a larger scheme tackling the labour concerns of all Europeans, which could reduce social tensions.

VI – Three Scenarios

A responsible Italian leadership would initiate debate on these issues with other EU Member States. In contrast, at the last EU Council meeting an apparent ‘political crisis’ between Conte and some EU partners (Macron, Merkel, and Borissov) was reported.

The Dublin Regulation should be overhauled, but narrow nationalist politics is creating stasis in the Union, and the Italian government’s intransigence is not helping matters.

The only positive news stemming from the muscular stance of the yellow-green alliance is renewed (enduring?) attention being paid to the migrant question, and to Italy as a strategic stronghold for a federal Europe, meaning the country could finally reap concrete political advantages as regards sharing the costs of receiving migrants.

Salvini has gone so far as to warn that if the rules are not changed on migration then Italy will withdraw its annual contribution.

It remains to be seen whether M5S leaders – presumably to the left of Di Maio – will be able to counterbalance this ‘green’ communication agenda. Can that faction defuse the ‘immigration affair’ and the radicalising narratives of La Lega? Will they succeed in reversing the positions they had to swallow to gain the levers of power, and finally make their 32% of electoral votes correspond with real political power?

One opportunity for the inexperienced M5S and its leaders – in contrast La Lega as La Lega Norde was in local government from the 1980s and national politics from the 90s – is to implement their economic and social platform, from which Salvini’s ‘immigration issue’ has diverted attention.

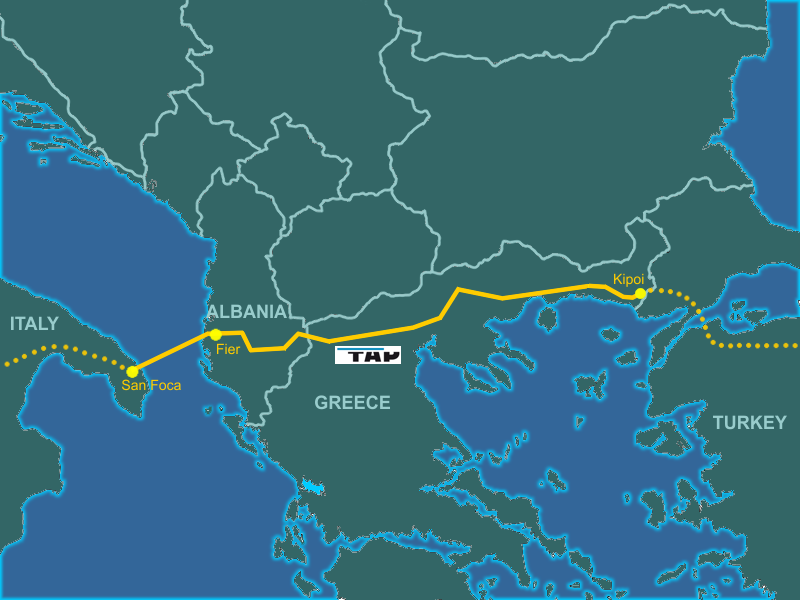

These include the reddito di cittadinanza (‘basic social income’) it promised voters, and long-standing environmental commitments, including the closure or modernisation of the ILVA iron plant in Taranto, and the blockage or relocation of the docking of the ‘Trans-Adriatic Pipeline’ in Puglia.

The current route of the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline.

There is also the issue of investment in social housing and infrastructures for workers, active employment policies and the restructuring of unemployment agencies, digitalisation and other services for SMEs, simplification of laws, and incentives for youth entrepreneurship.

Recently Di Maio, now heading a monstre Ministry reuniting Labour with Economic Development (Industry), has initiated an investigation into the feasibility of basic income, against the indifference or opposition of his La Lega partners. On these points, the interests of the historical Lega constituencies and the expectations of M5S supporters might seriously diverge.

La Lega’s leadership in the north of Italy, after years of regional and local governments, are perceived as guarantors of established commercial interests, tied to the former Forza Italia barons of the northern economy. Any M5S initiatives implying significant redistribution of public resources seem likely to create rifts.

The more the M5S pursues social and economic priorities the greater the prospect of divergence with La Lega. But if M5S renounces these social policies they risk division into right and left factions, just like the Democratic Party before them, making its prospects in the next elections uncertain. Failure to act could generate new alliances before the next elections.

Would this mean glory for the ‘green’ ‘Matteo’? Two scenarios present themselves to Italian citizens in the medium term. The first is an abrupt end to the coalition, involving a never-ending cycle of elections, in which La Lega pickpockets the right wing M5S votes, and attracts new voters from traditional centre-right parties; or perhaps restoring a political dowry to the prodigal son Silvio Berlusconi, and his centre-right Forza Italia heirs.

The second scenario is a revitalized (inspired by Spain’s Socialists perhaps) ‘Democratic Party’ leadership emerging to end the short-lived Matteo II’s era in Italian politics, supporting dialogue with the M5S , under Fico, and reviving the social movements that Matteo I sank

This could bring an end to the financial and economic stalemate which has ruined so many firms and families, unravelling a delicate social fabric so as to give an opportunity to demagogues like Salvini.

Nothing is shaped until everything is shaped. A third scenario could play out where the M5S and La Lega develop ties at institutional levels, and become an inseparable Populist force. To the leadership of the Democrats, and the new forces emerging in Italian civil society, the hard task is to play the cards in front of them.