It was sunny outside. Manus still felt something akin to minor guilt at lying in bed on a sunny day. Just having the option carried a guilt. He had spent most of his life not having to get up in the morning, not working, living off social security benefits.

There was a certain amount of guilt involved but it was easy to rationalize away. In a world that accepted the waste of half of its food production each day, and for thousands of kids to die of hunger each night, rationalizing guilt away came easy.

He would have liked to fight against the injustices of the world but it seemed like a global system with no head to cut off that wouldn’t pop back up immediately. Manus had not spent his life researching and exposing corporate crimes or hacking computers. He wouldn’t know where to begin with research and when it came to computers he was technologically challenged.

His lifestyle choice to just take drugs and scrounge off the state as much as they would allow had been as proactive a revolutionary stance as he could manage, which the less enlightened members of society failed to understand, instead viewing him as a lazy good-for-nuthen-opportunist-bum, but Manus didn’t hold it against them. ‘There but for fortune’ after all.

No, regardless of mainstream social exclusion, condemnation and relative poverty for someone living in the privileged sector of the planet, Manus had often enjoyed his choice: to lie in or get up.

This morning, however, he had allowed himself to be robbed of all enjoyment.

This morning he was cursed with the knowledge that he had pushed a young woman away from him.

She liked to keep her options open and he had texted her more or less demanding that she give him a definite date for their next meeting. In a ‘normal relationship’ this might well have been acceptable but this was not a ‘normal relationship’. In fact this was not a ‘relationship’. Avril had insisted from the start. She didn’t want a ‘relationship’. She liked to call round. Once or twice a week. Just for sex. And sex had nothing to do with anything. So Avril said.

But after a few months, Manus got used to her and when she didn’t call for a week or so he was pushing her for rights he didn’t have.

It was in the contract. She was younger than him by over two decades. All she wanted was a bit of fun and instead of being grateful he had pushed the last woman who would ever fuck him away. Now there was guilt.

He didn’t want to get out of bed all day. He was stupid and now he was condemned for his crime. Sentenced for the rest of his life to be alone.

(It wasn’t really true as his thirteen year old daughter who lived with him seventy-two hours a week every weekend would have been quick to point out. But this was the other ninety-six hours of the week, and he was alone.)

Ah the suffering and the pain.

He would lie with it all day. No, that might have been excusable had he been thirty or forty years younger, but he wasn’t and though he was very tempted to visit an old favourite familiar haunt, he was just too old. He knew he didn’t have that many days left to waste, no matter how favoured and familiar an old haunt it might be.

And he had things to do.

It was Assange’s birthday for a start. Manus was to meet people at Saint Stephen’s Green at a quarter past one. They were going to deliver a letter to the Australian embassy. Originally they had just talked of making a cake and Manus had thought to hassle a friend or two over to play guitar, and maybe see if they couldn’t get something like a small street party going. But that had been before Avril had ditched him. Since then Manus was lacking the strength or enthusiasm to hassle anyone. Yet again his broken heart had got in the way of political activism, or positive action of any kind.

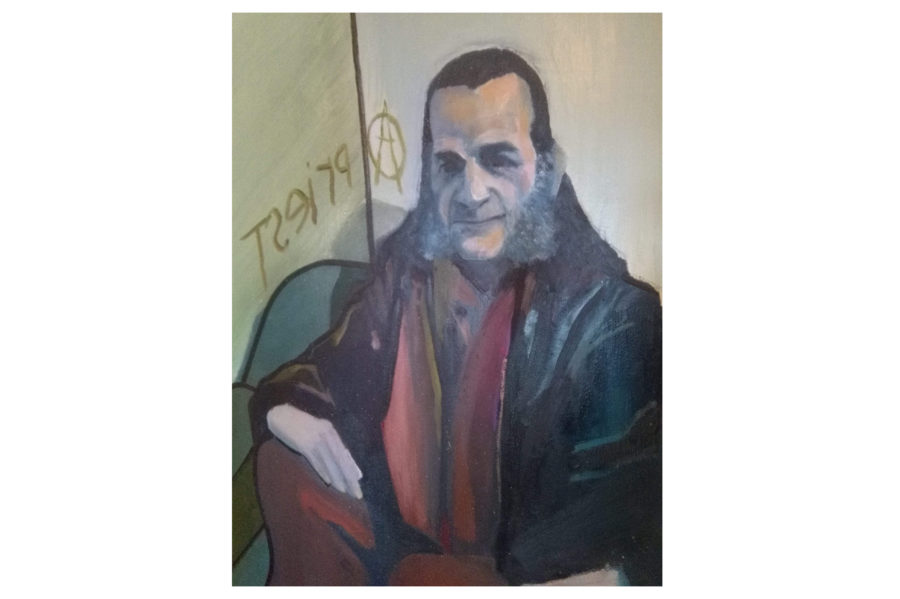

Ciaron O’Reilly had instigated the protest.

Amongst other things Ciaron had taken a hammer in his hands and damaged American war planes that would otherwise kill or harm the poorest people in the world.

Acting like a responsible citizen had earned Ciaron hard time in high security prisons, and Manus’s respect.

So perhaps it was for Ciaron, as much as for Julian, that Manus would get out of bed and make his way into town. Manus imagined Julian Assange wouldn’t be overly impressed with their protest. Nobody could be. There would be half a dozen people, a dozen people at the most.

Most passers-by wouldn’t know who Julian Assange was.

Against a tsunami of banners and all the technology money can buy, which told people that what Julian Assange was doing just wasn’t important, Manus and a few others would stand with a single banner saying ‘free jullian assange’. The few standing with the banner, if they got noticed at all, would look like weirdo nutters. Manus was going to go, perhaps just to show some solidarity with the weirdo nutters.

Around 11a.m. George Kirwan called for Manus.

George was one of them smart ass bastards from a fairly privileged background; a former chairman of a Trinity debating society, who would come up with a nuanced argument against anything you said. Manus was one of those dumb ass fuckers from a fairly unprivileged background, where debating skills ran from shouting to yelling personal threats, to physical violence.

Manus asked George why he wasn’t going to the protest. George said he didn’t protest anything because he thought it was ineffective. Manus asked if all ‘protest was ineffective’ then should we do nothing? George backtracked saying ‘he very seldom protested and saved his energy for the ones he felt were important, which did not include Assange.’ Furthermore, George wasn’t sure Assange was his political ally since Wikileaks had, ‘not just published, but directly funnelled leaked documents to the Trump campaign first’; George continued: ‘directly dealing with a dime store Hitler was naïve in the extreme and a wrong act’.

It didn’t ring true for Manus that Assange or Wikileaks would be dealing directly with the Trump campaign, though as usual he hadn’t done much research and couldn’t say with any certainty. George as always was certain: ‘there was a server in Wikileaks communicating with a server in Trump Tower’, George swore it with rather more venom in its delivery than the truth needed. Trinity’s training got lost and George could be as emotive as any uneducated thug when he defended a false position.

Manus said that since he had started speaking for Assange he had heard all kinds of negative fact and fiction. All of which for Manus sidestepped the main issue.

Publishing the crimes of the powerful should be applauded, not a punishable offence.

For none of these other reasons, fact or fiction, would Assange be imprisoned.

Wikileaks was known all around the globe for telling the truth. It had an effect on the way the world was perceived, with potential to affect how it’s citizens and environment were treated.

Allowing the Wikileaks founder to be imprisoned would send a clear message ringing around the world. Exposing government and corporate crimes would not be tolerated.

George lost some of his evangelical zeal against Assange and relented with, ‘their wasn’t enough evidence against him for a conviction, but enough to lose him the support of the left.’

George spouted on then about some group in America who used to fight legal cases for poor black communists to have the right to preach communism and then they fought for rich white fascists to have the right to preach fascism. Then they decided they didn’t have enough resources to fight for both and decided to just fight for the Commies. Not that he was saying Assange was a fascist.

How had the so-called left gone along with this crap? How had the most effective exposer of corporate and government crimes been turned into the left’s enemy, or person of no worth, or person they least wanted to defend? The answer was obvious, corporate power had attacked Assange because he exposed their crimes and the corporate media swamped the world with their attack, but it was the left’s acceptance of such obvious diversions and spurious attacks that bothered Manus.

Manus had a frazzled brain. Too much: drugs, drink, punches to the head. He couldn’t always take in a lot of info and he could retain less. George hadn’t done half as much drugs or drink and had probably never been punched in the head in his life. Manus wasn’t fit for arguing with him.

The two were friends of a sort. They had both protested against the Dublin Housing Crisis; they had both helped out at a social centre. They helped each other sometimes. For all their differences they had things in common.

George had brought his three-year-old daughter Paulina. Paulina and Manus had gone through a number of high and low points over the three years of her life. Manus had been a fun distraction one night while both her parents had sneaked off but when Paulina became aware of the dirty trick that had been played on her she screamed all night. It had taken a long time but Paulina was gradually forgiving Manus. She got Manus to flush the toilet for her. Which Manus did again and again and again and again. Paulina was delighted. It was nice for Manus too, to perform a task that seemed a worthwhile and appreciated service.

Nick phoned and arranged to meet Manus on Saint Stephen’s Green. Like Manus, Nick came from the North. Like Manus, Nick had been called names and spat at a lot when he walked the streets as a youth. They both shared the experience of gangs of loyalist thugs throwing bricks and bottles and chasing them. Manus was a taig in a mostly prod area and could run for one of the taig streets. Nick was actually a prod in a totally prod area but his family would have been the only black family in his whole estate. Loyalists in the North of Ireland were known for their sectarianism, but Nick’s family gave them a chance to prove they were just as racist. Nick developed fighting skills whereas Manus was just a great runner. Manus figured Nick had always tried and usually managed to beat the bastards at their own games. He could fight better, play sports or chess better and stand at the bar and talk bullshit about football better than anybody.

Nick was over six feet tall and when he let his dreadlocks out of his big hat they came down to the floor.

Manus and Nick had coffee, sat on the grass on Saint Stephen’s Green. Manus babbled about his own child’s graduation from primary school and how it looked like an American teen movie. And how he felt depressed since he had just pushed that woman away. And how he hoped to get a ‘coffee with Chomsky’ van together which would permanently play Chomsky speeches or Democracy Now! episodes or CounterPunch news, or any alternative to corporate news and views of the world. Everywhere you looked there was a corporate message. One small screen wasn’t going to achieve much, but it just might keep his personal sanity.

Nick loved the idea. Nick was a cobbler by trade but still hoped to build a studio and record his own music. He had two grown boys up North who visited regularly, but Nick at fifty years of age now lived in Dublin with his new partner and their five year old son Thor.

Nick babbled about his partner going to some medium who had said Thor was a really old soul. Manus’s mother used to go in for that type of stuff. Nick also went on about how England was still in the World Cup and how Manus, even though he wasn’t into football or nationalism, had to join in the world’s prayer that England couldn’t win the World Cup. The world would never hear the end of it. They still hadn’t shut up about their win in 66.

At least, thought Manus, Nick didn’t repeat the football being more serious than life or death crap.

Manus and Nick met May O Byrne at the main gate outside Saint Stephen’s Green. Nick had to go to pick up his kid but Manus introduced them anyway. Telling Nick: ‘come on and meet this one she’s cool.’

‘Nick this is May she’s an activist. May this is Nick he’s not stopping today but he’s one of us.’

Nick went on and May and Manus stood alone.

May had the petition letter, but said she wasn’t that pleased with it because it quoted Obama. The fact that Obama had been responsible for so many deaths in his time put May off. Manus shrugged. He didn’t reckon the Australian government would give a shit what the letter said. They were never going to protect Assange. What government in the world was going to thumb its nose at America?

May was even older than Manus. She said her husband wasn’t well enough to attend. He was eighty-five. Her hubby had been a newscaster in Australia. She said he could see the telexes that came into the news office which never got read. After a while he found it impossible to put on a face that looked like it believed what it was reading and so he lost his job.

May said there was another Australian coming. A woman called Kate. Manus tried to check himself from his ridiculous notions of finding a partner, long or short term, in Kate. At his age looking for a partner. How long did he think he had left? Still his mind ran on. She would probably have rolls of fat hanging over her pants and a squashed up ugly face. He was shallow.

She turned up. Fit-looking and highly attractive. When May went to shake hands Kate insisted on a hug. Manus got a hug too. A bit of much needed physical for Manus. She had been visiting her parents. Catching a flight back at the end of the week.

Just right for a non-committal shag on a holiday thought Manus.

Kate said she had emigrated to Australia on her own in the seventies. Had Manus heard that right. Emigrating in the seventies on her own made her around his age. Was that possible? Had he found an attractive woman from his own age group? Could she feel attracted to him?

Youth went for sexual gratification, age expected accomplishments or at least a place in society. Manus was the least accomplished person in the world, with the lowest place in society.

He had to stop with the negative self-image. It was that Avril ditchen him thing. It was the getting no nouky. Being the least accomplished person in the world or his place in society didn’t bother him so much when he was getting laid.

Kate had been shoe-shopping. ‘Well shoes are just so expensive in Australia.’

Believe in the corporate portrayal of the world or not you still had to live in it. And despite his own choice, he understood that being a bum was not a popular preference.

Sid turned up with his bowler hat, scarf, waistcoat and corduroy trousers. A talented singer song writer. Sid and Manus were close enough in years. They talked of Ciaron O Reilly’s unceasing efforts. They both did little bits now and again but Ciaron was full time, twenty-four-seven, year-in year-out. They talked of their kids. Sid’s daughter, born when Sid was in his twenties, was in her forties now. Sid said he had been there when his daughter was a child but he may as well not have been. Sid didn’t drink now but he had been a hard drinker. Manus was coming on fifty before a woman had decided not to abort his kid. Age must have granted him some semblance of sense then, as he had stopped drinking and hard-drugging in order to look after his daughter.

It had clearly been the better buzz.

Liam arrived. Almost in his forties, with a twenty-one year old son that he had fought for and gained joint custody over when the child was young. A clean cut man from a stable background. Manus and Liam had put the movie Underground: The Julian Assange Story on in a social centre before Assange’s sixth year in detention. They were useless at getting an audience. They got the usual suspects: June; Sid; Manus; Liam; Dave; and Brian (Brian couldn’t stay though, he was no spring chicken and probably didn’t enjoy the music plus, any talk of computers confused him. He had never used one). There had also been a new face, a Polish girl who actually came to the protest the next week. Liam had remained upbeat and positive. The Polish girl was a new convert. One at a time huh? Even if he was getting laid, getting paid and had a place in society other than lowest, Manus’s optimism couldn’t turn the idea of one person into the possibility of victory. Liam was realistic enough too though. Like Manus he saw no victory possible through their pathetic efforts. And like Manus he didn’t know any other tactics. And while the effort and its lack of effect made them feel useless, not to make the effort made them feel worse.

Paul arrived. Manus didn’t know much about him. Seen him at a few protests. In his thirties maybe.

He lived down the country somewhere, but if he was in the capital and something was happening he would go. He looked a solid, stubborn sort that would be good to have beside you in a line against thugs in uniforms.

Ann arrived. Manus had never met her before. She was writing a piece for a Russian magazine. Younger than Manus by a few decades. In a flouncy dress. Manus’s attention switched. Them flouncy summer dresses always got Manus.

Sometimes he could be such a letch.

They walked through the park. Manus asked Sid if he had had much success as a singer-songwriter. Sid said, ‘No. Thank god.’ ‘Why? Did you not want success?’ asked Manus, to which Sid replied ‘my head’s so big already it would have blown up completely. Sure I’d a had to get myself a new hat and everything.’

Manus understood how difficult it would be to cope with success. And agreed with Sid’s sentiment, but in actuality he could have done with a bit of it.

They walked through the park and after a wrong turn or two found the embassy.

Martine was there with his two kids who were both under ten years old. Martine had thought of becoming a priest, but had backed out at the last minute. Thank fuck.

The letter requesting that the Australian government start looking after Julian Assange’s human rights, signed by two and a half pages of Australians living in England and further afield, was read. Photos were taken. Manus held a banner: ‘free Julian Assange’.

That was it.

Martine and his kids went off. Everyone else decided to go to the park for coffee and tea and small buns with a single letter of the birthday boy’s name on each one. Thirteen buns.

They had the banner spread out in front of them on the grass.

Free Julian Assange.

Kids were still starving to death while half the world’s food production was being destroyed. Ecological and nuclear disaster threatened the planet like never before while the corporations’ need for constant profit kept pushing us all towards said disaster. And Julian Assange was hold up in some room in London, threatened with life imprisonment for publishing the truth.

And it was a beautiful sunny day in Dublin’s Saint Stephens Green.

The group talked and exchanged phone numbers. Manus didn’t offer or ask and wasn’t offered or asked for a phone number.

Sid called to him as though the two should walk off together, but Manus stalled. He wanted to walk with Sid but what was Kate doing?

Liam was showing Kate where the museum was. Manus went too. Perfect, Liam would walk off and Manus could show her round. It was almost too pat. Walk and talk round a museum with an attractive woman he had met at a protest. Engaging conversation and curiosity glances. They would get some food. Time would pass and she would have to get the last bus back out the country unless she wanted to stay in Dublin for the night.

As usual his mind ran on fantasies. but his mouth said nuthen.

Liam hugged her goodbye.

Manus hugged her goodbye too.

On their walk through town Liam asked Manus if he would like to write a letter to Julian. Manus kina shrugged his laugh. Manus had spent his life trying to ignore or block out what he thought he could do little about. And now he wanted to write to Julian and say he supported him. Hopefully there were better more effective supporters than Manus.

Did you know that Cassandra Voices has just published a print annual containing our best articles, stories, poems and photography from 2018? It’s a big book! To find out where you can purchase it, or order it, email [email protected]