The problem with writing about the U.S. Democratic Party, whether analytically, historically, or even as a matter of praxis, is that it has all been said or tried before.

Want to run party candidates on a left-wing (or progressive, or whatever?) platform? Recall the so-called Alliance Yardstick, when the Farmers’ Alliance in 1890 held Democratic Party candidates it endorsed to its full program, including such items as the nationalization of the railroads, a progressive income tax, and significant monetary reform. They got hundreds of candidates elected — most of whom promptly abandoned the agreement.

This led to the formation of the People’s Party in 1892, which did well by the standards of a third party, before largely getting gobbled up when the Democrats adopted one of their main planks (free silver) in 1896.

Or, for that matter, the experiences of the Democratic Socialists of America in the 1970s and 1980s, when formerly third-party socialists led by Mike Harrington surmised that with the conservative white supremacist wing of the Democratic Party leaving in droves, what remained could be turned in a social-democratic direction. Problem was (among many others) the trade-union leaders, whose support the DSA was banking on, failed to lend their support, and aside from Ron Dellums in the Bay Area, the DSA devolved into an organization of long-in-the-tooth ex-New Leftists and left-talking trade-union bureaucrats, until the past few years pushed its membership north of 50,000, and its median age roughly millennial.

So what does a socialist/leftist of any stripe do about this behemoth of an organization that isn’t leftist in any meaningful sense — even the crappy sort of continuous sell-out leftism of the Irish Labour Party variety — but nevertheless fills that space in a first-past-the-post system that naturally generates two main parties?

Moreover, what are the chances of doing so in a political landscape that hasn’t seen a new major party emerge since the Republicans first ran John C. Frémont for president in 1856? This gets us to a dilemma facing any practitioner of reform politics in the United States: do you go into one of the old Parties and try to take it over from within, or do you set up a third party to oppose both the Democrats and Republicans?

There are several advantages, at least perceived, of taking over an established party. In the first place, you already find an infrastructure. There is a central fund, precinct captains, name recognition. Many people vote out of habit, too, so habitual Democrats might well continue voting Democrat in spite of more radical candidates.

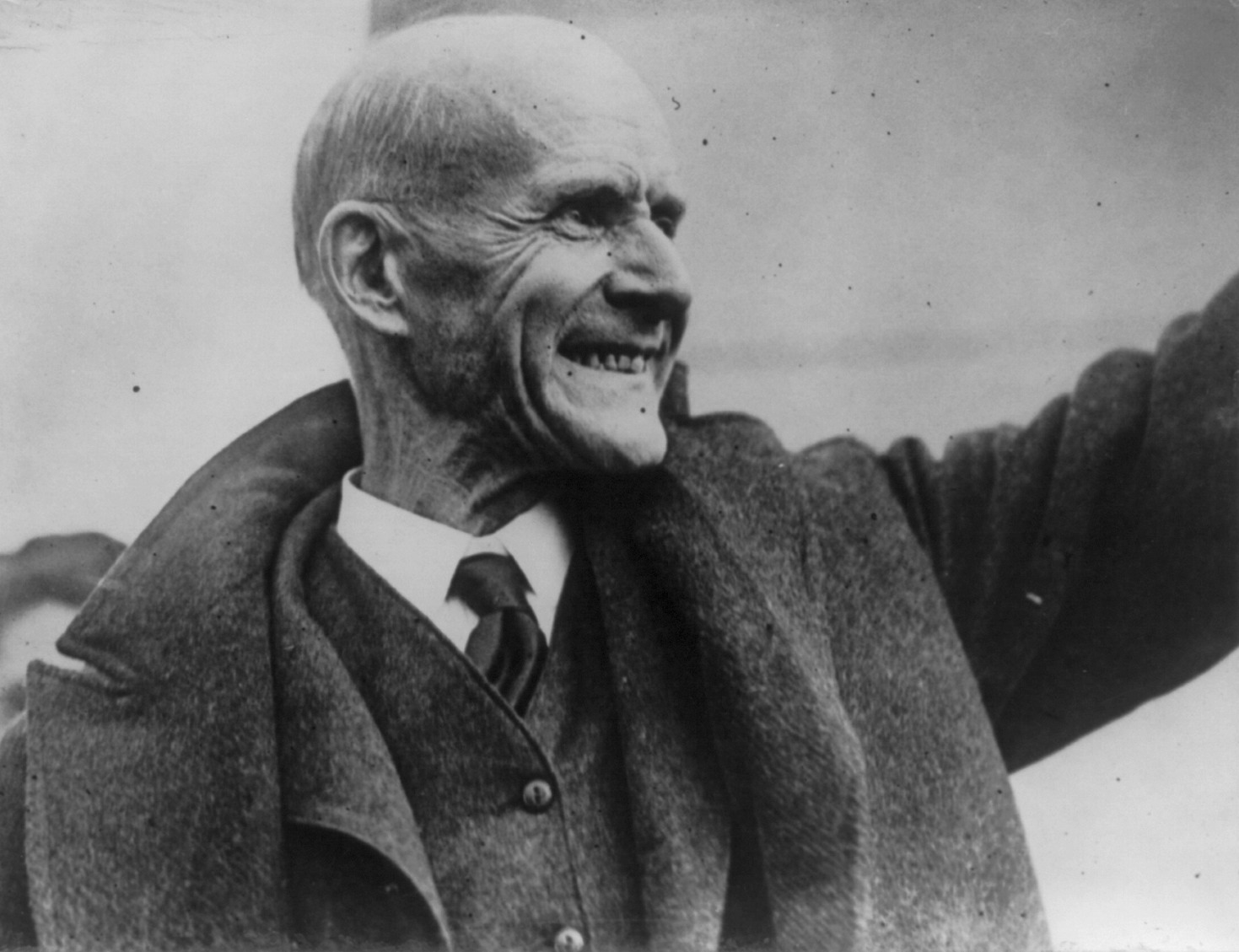

Starting from scratch and taking on deep-seated traditional loyalties, moreover, can be daunting. The two major American political parties, after all, have remained a constant since the Civil War. Taking them on has not proven terribly easy, with the single-best showing for a third-party socialist candidate to date being that of Eugene Debs, who won 900,000 votes in 1912, which sounds impressive until one realizes that was roughly 6% of the total.

The problems with capturing one of the two major parties for an insurgent political movement, though, flow from this same strength. Though the Democrats and Republicans are, to a certain degree, malleable, they are — and were — nonetheless well-established institutions. Taking them over was easier said than done. If one managed to capture either major party, one would probably not capture it all at the same time. Donations can dry up — or be used to win over politicians to return to the fold.

Moreover, the considerable bureaucracy of each party can be wielded against internal dissent. Ask Bernie Sanders. Getting one’s own candidates nominated is only part of the battle.

The creation of a third party has one considerable advantage, notwithstanding the need to create new machinery in the face of deep-seated party loyalties. Importantly, you retains control of your message. The party discipline affecting your elected officials is your own concern. Still, gaining and maintaining ballot access is fiendishly (and deliberately) difficult. When a reform-minded third party does shows up in mainstream debates it is usually as a swear word in the mouth of Democrats, who say you robbed them.

This outrage, notably directed at Ralph Nader in 2000 and Jill Stein in 2016, is contemptible, particularly given the outrage, both muted and open, emanating from the establishment liberal punditocracy at Bernie Sanders running as a Democrat even though he isn’t a real Democrat! (Cue ugly crying, specious accusations of misogyny and racism, and behind-the-scenes machinations with the Clinton campaign.)

If one works within the Democratic Party, one is engaging in a hostile takeover; if one works outside it, one is a spoiler. The nabobs of liberalism are, naturally, opposed to both because they are opposed to any kind of anti-capitalist or anti-imperialist politics.

Seth Ackerman, writing in Jacobin, proposed something of a both/and strategy in an article entitled ‘A Blueprint for a New Party’. Noting that the Democrats, and Republicans, unusually for political parties in much of the world, are not really ‘parties’ in the way most people, most places think of such entities. He deserves to be quoted at length:

Beneath our winner-take-all electoral rules, we also have a unique — and uniquely repressive — legal system governing political parties and the mechanics of elections. This system has nothing to do with the Constitution or the Founding Fathers. Rather, it was established by the major-party leaders, state by state, over a period stretching roughly from 1890 to 1920.

Before then, the old Jacksonian framework prevailed: there was no secret ballot, and no officially printed ballot. Voters brought their own “tickets” to the polls and deposited them in a ballot box under the watchful eye of party workers and onlookers.

Meanwhile, the parties — which were then wholly private, unregulated clubs, fueled by patronage — chose their nominees using the “caucus-convention” system: a pyramid of county, state, and national party conventions in which participants at the lower-level meetings chose delegates to attend the higher-level meetings….

In the 1880s and 1890s, this cozy system was disrupted by a new breed of “hustling candidates,” who actively campaigned for office rather than quietly currying favor with a few key party workers. When informal local caucuses started to become scenes of open competitive campaigning by rival factions, each seeking lucrative patronage jobs, they degenerated into chaos, often violence.

Worse, candidates who lost the party nomination would try to win the election anyway by employing their own agents to hand out “pasted” or “knifed” party tickets on election day, grafting their names inconspicuously onto the regular party ticket.

Party leaders were losing control over their traditional means of maintaining a disciplined political army. Their response was a series of state-level legislative reforms that permanently transformed the American political system, creating the electoral machinery we have today.

Ackerman’s argument is that with the state moving in to take over a key part of internal party life — the selection of candidates — via primaries, getting on the ballot if one is not in one of the major parties can be intensely time-consuming (This, however, depends to a degree on the state — as each one has different electoral laws).

On the other hand, Ackerman acknowledges that the demands of a major party in regards to quid-pro-quo for any meaningful support can make that approach untenable too. Ackerman’s proposal for a new type of left-wing party also should be quoted at length:

The following is a proposal for such a model: a national political organization that would have chapters at the state and local levels, a binding program, a leadership accountable to its members, and electoral candidates nominated at all levels throughout the country.

As a nationwide organization, it would have a national educational apparatus, recognized leaders and spokespeople at the national level, and its candidates and other activities would come under a single, nationally recognized label…. In any given race, the organization could choose to run in major- or minor-party primaries, as nonpartisan independents, or even, theoretically, on the organization’s own ballot line.

The ballot line would thus be regarded as a secondary issue. The organization would base its legal right to exist not on the repressive ballot laws, but on the fundamental rights of freedom of association.

This is a deft, if perhaps conjunctural way around the problem — ballot party is explicitly not one’s real party. The challenge, though, is in the implementation.

The case of DSA member and presumptive New York congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is instructive. After scoring an upset against Queens Democratic Party satrap, and heir apparent to Nancy Pelosi, Joe Crowley, Ocasio-Cortez, an intelligent, charismatic twentysomething who, with the septuagenarian Sanders has become the face of ‘democratic socialism’ in the United States, seems at times unclear as to whether she is in the first place a Democrat or member of the ‘movement’ that propelled her to success.

Upon being confronted on her entirely decent statement against the Israeli occupation of Palestine this July, she backtracked into wishy-washy and vague formulations like: ‘Palestinians are experiencing difficulty in access to their housing and homes. Oh I think — what I meant is that the settlements that are increasing in some of these areas and places where Palestinians are experiencing difficulty in access to their housing and homes…’ and ‘I am not the expert at geopolitics on this issue. I am a firm believer in finding a two-state solution on this issue, and I’m happy to sit down with leaders on both of these — for me, I just look at things through a human-rights lens, and I may not use the right words. I know this is a very intense issue.’

This is not, as many pundits both rightist and centrist have intimated, a matter of the pretty young lady not knowing what she is talking about. It is a matter of trying not to piss off the AIPAC-aligned majority of the Democratic Party, while not entirely throwing the Palestinians under the treads of a Merkava tank.

In its own way, just as gratuitous was AOC’s slobbering Tweet when pro-war, corporate greedhead and all-around shitbag John McCain finally slipped this mortal coil. To wit: ‘John McCain’s legacy represents an unparalleled example of human decency and American service.’ Why don’t you tell us about how Princess Diana is ‘the People’s Princess,’ and a veritable ‘candle in the wind’, while you’re at it?

The question of orienting towards a party whose leadership views even mild reforms such as single-payer healthcare and maybe taking, you know, a pass on a few of the major imperialist clusterfucks of the past nigh-on two hundred years has been a fraught one for the left for almost as long as there has been an American left.

The AOC case illustrates that while being a self-described democratic socialist and having a (D) next to your name on television may not be mutually exclusive in an absolute sense, it is in tension. We shall see how she and a handful of other elected DSA members handle this, with some hope, and no small apprehension. It has gone horribly wrong before.