I first came across Dragana Jurišić’s work in the National Gallery of Ireland, when her ‘Tarantula’ was displayed as part of the ‘After Vermeer’ exhibition in 2017. ‘Tarantula’ was a contemporary response to the Vermeer exhibition, which featured a series of photographic self-portraits of overlapping dancing figures. Jurišić says she was ‘immediately struck by the two main subjects of Vermeer’s paintings: ‘women in domestic settings and the light’. Depiction of women in Vermeer’s portraits led Jurišić to consider the female condition, and ‘pre-conditioning’ more generally, in terms of the rules women must follow in life; their pensiveness and meditative status, which gives way to a mesmerised storm.

Jurišić recalls the main character of Nora in Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, first performed in 1879. Nora leaves her designated role in life, daring to partake in the dancing ‘struggle for life’. Similarly the mythical Tarantati women of Italy, once bitten by the spider, succumb to ‘trance-like dancing’, as the only way to access the euphoria of free expression. Jurišić’s dance, without resorting to provocative suggestions or techniques, traces a visual experiment that almost fulfils the lines of a classical figure, a preparatory drawing disclosing the artist’s creative process. As in Michelangelo’s sculpture ‘The Dying Slave’, these are unfinished sculptures, undressing themselves in the social marble, liberating their true shape from a carcass, not fully, but without shame, while displaying the melancholy and conflict of the process of self-cognition. Vermeer’s women are stuck in a composed, but not acquiescent pose, which recalls contemporary anxieties. Jurišić untangles Vermeer’s forms and empowers the female, and herself as a woman, unmasking the muses, symbols that still inform contemporary culture appreciations.[i]

Some months later I walked through Jurišić’s latest exhibition, ‘My Own Unknown’, at the Gallery of Photography in Dublin’s Temple Bar, which recalls women who wanted to free themselves from patriarchal constraints. Into Jurišić’s personal story is sewn the mysterious life of her aunt Gordana Čavić. Čavić, like Ibsen’s Nora, disappeared from her assigned role, and native country, Yugoslavia, in the 1950s, dying in Parisian exile in the 1980s: ‘A life shrouded in mystery, it involves tales of multiple identities, illicit sex and espionage’. Out of Jurišić’s archival photographs, the artist recreates a diary of a personal rebirth from a cryptic loss, defining her life as woman and artist:

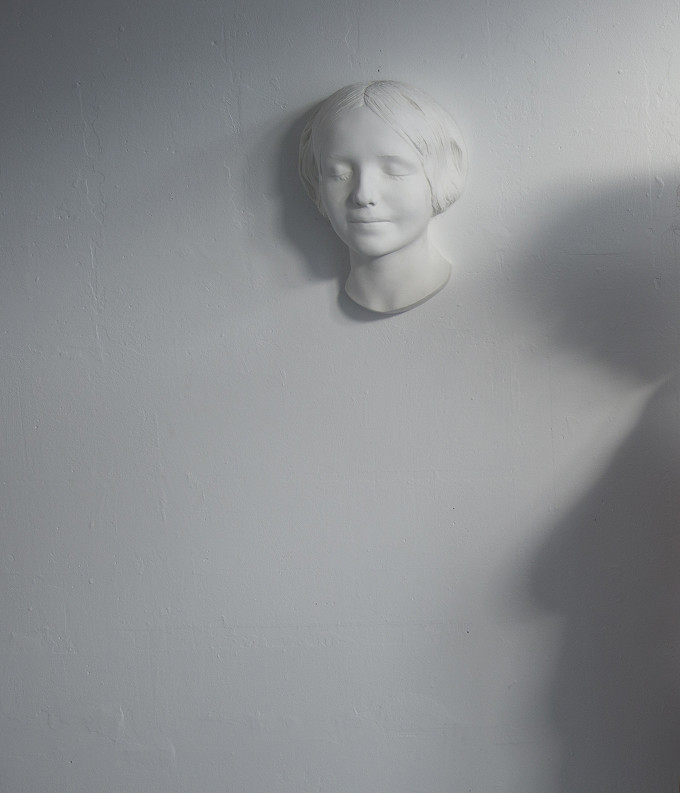

My initial questioning of this statement took me to Paris to commence an exploration on L’Inconnue de la Seine, the name given to a young woman whose body was allegedly recovered from the River Seine, and whose death mask was cast in a bid to identify her. Her serene and quiet beauty became a muse for artists.

The mask and idealistic form is an object of veneration: the fake perfection of a muse, veiled by cultural layers, and detached from any real process of accomplishment. Jurišić’s own undressing, displaying her true ‘body’, provides an unflinching interpretation of her own form.

What Jurišić knew for sure was that Gordana Čavić was made of much harder stuff than L’Inconnue de la Seine:

Suddenly I was back at 11 years old, looking at a funeral procession that was beyond extravagant. … Who was she? I asked my grandmother, She just shuffled uncomfortably in response. Behind me I could hear whispers of two men from down the road.

L’Inconnue de la Seine represents the inspiring perfection ‘protecting’ the viewer from experience of the real body; the ‘other woman’, which could alter the common sense experience, and reinforce devotion to old beliefs. Who is she? Who is Gordana Čavić, Nora, or the artist Dragana Jurišić?

In Ibsen’s Women Joan Templeton observes the muse’s path through the centuries. Her powerful analysis of femininity recalls Jurišić’s artistic ambitions: ‘For Gilbert and Gubar … the lady is our creation or Pygmalion’s statue. The lady is the poem.’[ii] The lady is the sculpture, the statue Pygmalion carved and fell in love with, like L’inconnue de la Seine. This is a cast and frozen idealization of femininity. Templeton approvingly cites Simone de Beauvoir:

But women exist without men’s intervention and thus while ‘woman’ incarnates men’s fantasies, women proves the falsity of the fantasies … Man’s need for woman to remain always the Other. … Woman is necessary to the extent that she remains an idea into which the man can project his own transcendence; but she is danger as an objective reality existing for herself and limited to herself.

A more urgent consciousness is emerging in our daily experience, beginning with many women’s revelations of sexual violence during the #MeToo movement, and willingness to alter a passive condition of acceptance. Contemporary women are fighting back against an old, still unresolved disadvantage: their objectification as muses.

Why is ‘the woman’ still an ideal, mythical presence, her real body still censored by intangible projections? Why do many men feel an inadequacy in front of real presences, to the extent of displaying hostility or aggression – real or unconscious – towards that which is not a fantasy? Why are artists still confronting opposition to representations of real existing forms, from ludicrous rules against displaying women’s nipples on social networks, to outright censorship of nudes in exhibition advertisements, while at the same time, our visual environment is filled with sexualised content? Are these taboos veils that hide the truth? Is it the ideal of the muses we are still battling against?

Not only is the idea of woman in need of revolution, our concept of masculinity needs to be reappraised. According to Dr Arne Rubinstein in The Making of Men: ‘in the healthy man’s psychology, a man sees himself as part of the universe, not the centre of it; he takes full responsibility for his actions, he deals with his emotions and he looks for a healthy relationship with the feminine.’ But ‘the role-modelling and mentoring for boys and teenagers is very poor, and the messaging is terrible.’[iii] Rubinstein’s organization attempts to reconcile the masculine and feminine in men.

In her 1929 novel A Room of One’s Own Virginia Woolf endeavoured to awaken awareness of gender inadequacy. She suggested society should reconsider and re-educate our basic perceptions of sexuality, and the condition of women in the world, beginning with the artistic and creative processes:

For certainly when I saw the couple get into the taxi-cab the mind felt as if, after being divided, it had come together again in a natural fusion. The obvious reason would be that it is natural for the sexes to cooperate … But the sight of the two people getting into the taxi and the satisfaction it gave me made me also ask whether there are two sexes in the mind corresponding to the two sexes in the body, and whether they also require to be united in order to get complete satisfaction and happiness?[iv]

In the last part of her exhibition ‘My own Unknown’, Jurišić explores her self-portraits and diaries, concluding the exhibition with a previous work made in Dublin in 2015, employing the same technique as ‘Tarantula’, but overlapping photographs of one hundred women posing as nude muses in front of her. They direct their own poses using a chair and a veil, each identify themselves with one of the nine muses of Greek mythology: Calliope, Clio, Euterpe, Erato, Melpomene, Polyhymnia, Terpsichore, Thalia and Urania.

One of the final portraits is ‘The Mother’, an overlap of all the muses. This is Mnemosyne, mother of all the Muses, goddess of memory. On top of one another the bodies look like layers of negatives, memories overlapping into a majestic image. This conveys a scribble, an incomplete creative process, an operation of cognition in the ‘struggle for life’. Jurišić writes:

The idea of the muse often evokes images of a male artist and a passive female muse. The female muse is often depicted as nude in visual art. And in turn “the nude” – one of the biggest clichés of Western art tradition, is a genre predominantly inhabited by male artists. At the beginning of April 2015, I began the task of photographing 100 female nudes over a period of five weeks.

A powerful expression of ourselves is still needed, not only a female view on female gaze, but an entire recreation of feminine and masculine interpretation. An ‘ownership over their body’.

Gordana knew that she came to Paris to survive. Survive at any cost. Shed her skin. Shed her past. Forget about the people she left behind. Or not. But she is not going back. She will never go back.

The goddess mother of all the muses is the goddess mother of a faded memory, like Jurišić’s aunt Gordana Čavić who ‘was so beautiful, like she was her own creator.’[v]

[i] National Gallery of Ireland, ‘Dragana Jurisic: Tarantula’, https://www.nationalgallery.ie/dragana-jurisic-tarantula, accessed 15/11/18.

[ii] Joan Templeton, Ibsen’s Women, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp303-305

[iii] Quoted in: David Leser, ‘Women, men and the whole damn thing’, Sydney Morning Herald, 9th of February, 2018, https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/the-great-sexual-reckoning-how-did-we-get-here–and-what-happens-now-20180124-h0npcc.html, accessed 23/11/18.

[iv] Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, London, Hogarth Press, p.113

[v] Dragana Jurišić ‘My Own Unknown’, 2014, http://www.draganajurisic.com/my-own-unknown/4587594312, accessed 15/11/18.

Dragana Jurisic, ‘Tarantula’. Archival pigment print, 2017. © the artist.

L’Inconnue de la Seine, http://draganajurisic.com/my-own-unknown/458759431

Dragana Jurisic, Erato. © the artist.

Dragana Jurisic, Euterpe. © the artist.

Dragana Jurisic, The Mother. © the artist.